Promotion

Sign up for our newsletters to receive 20% off! Shop now. Exclusions apply.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

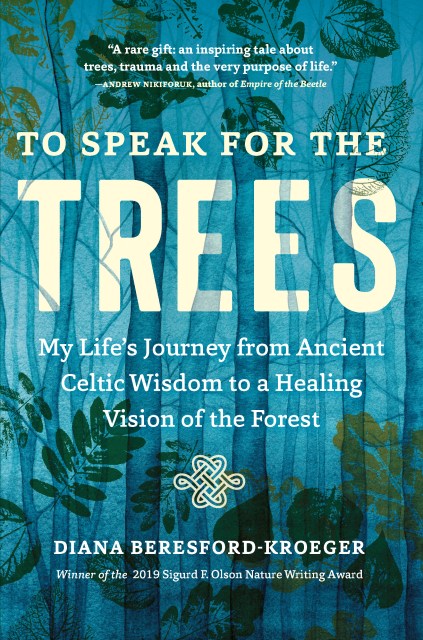

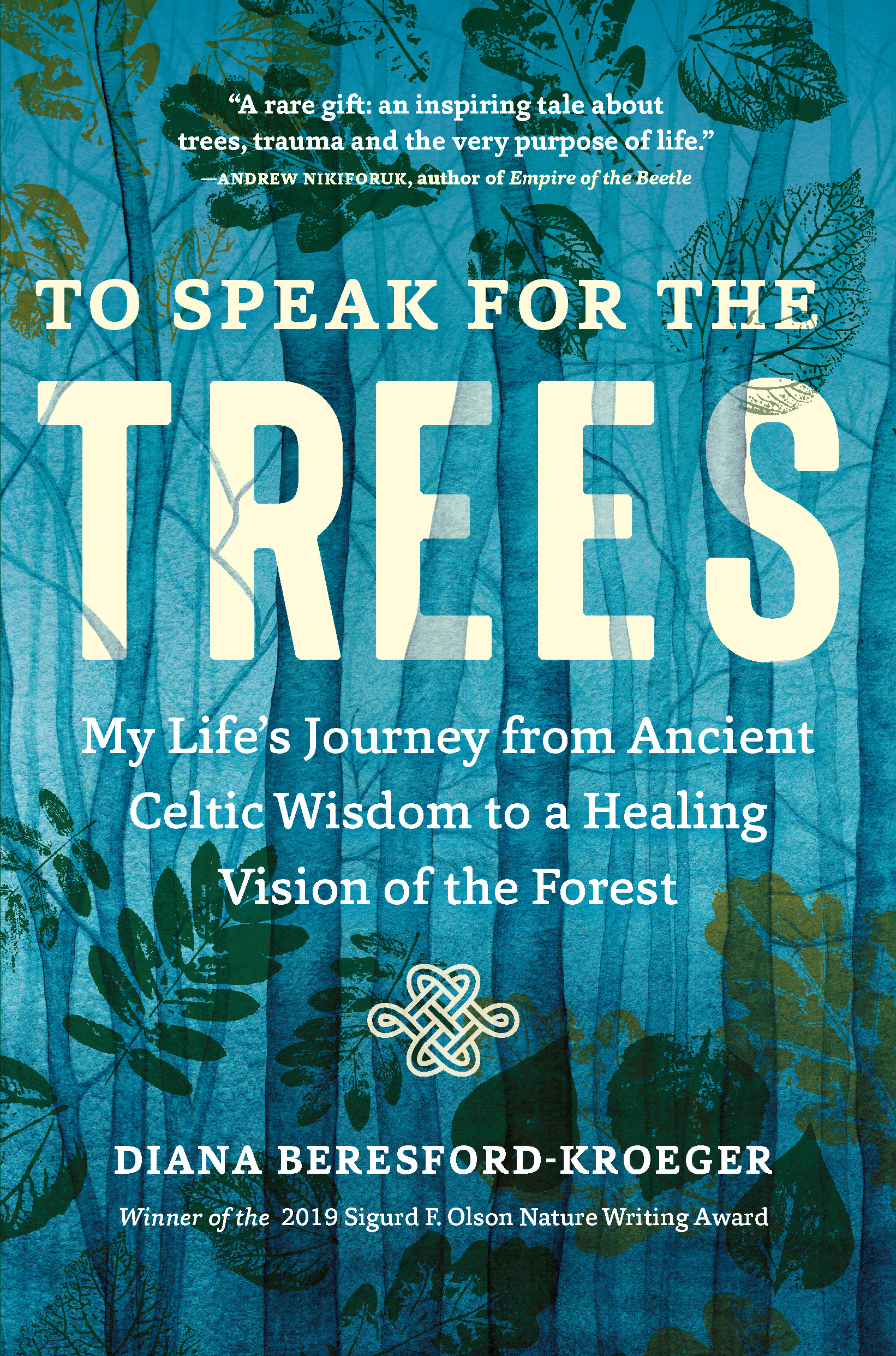

To Speak for the Trees

My Life's Journey from Ancient Celtic Wisdom to a Healing Vision of the Forest

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$22.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $22.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 5, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

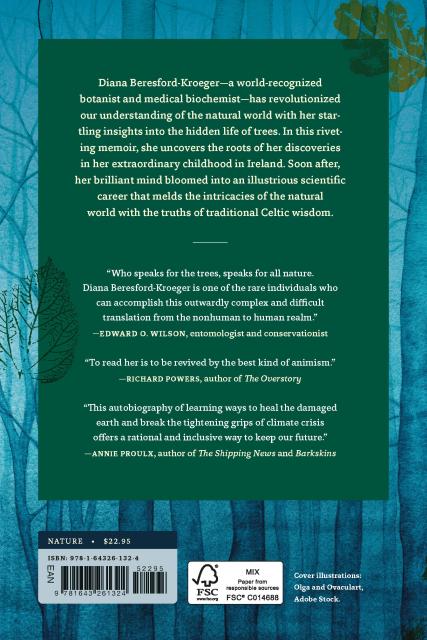

Diana Beresford-Kroeger—a world-recognized botanist and medical biochemist—has revolutionized our understanding of the natural world with her startling insights into the hidden life of trees. In this riveting memoir, she uncovers the roots of her discoveries in her extraordinary childhood in Ireland. Soon after, her brilliant mind bloomed into an illustrious scientific career that melds the intricacies of the natural world with the truths of traditional Celtic wisdom.

To Speak for the Trees uniquely blends the story of Beresford-Kroeger’s incredible life and her outstanding achievement as a scientist. It elegantly shows us how forests can not only heal us as people but can also help save the planet.

-

“Using science and Celtic wisdom to save trees (and souls)…Beresford-Kroeger has been working to save some of the oldest life-forms on Earth.” —The New York Times

“Who speaks for the trees, speaks for all nature. Diana Beresford-Kroeger is one of the rare individuals who can accomplish this outwardly complex and difficult translation from the nonhuman to human realm.” —Edward O. Wilson, entomologist and conservationist

“A rare gift: an inspiring tale about trees, trauma and the very purpose of life.” —Andrew Nikiforuk, author of Empire of the Beetle

“To read her is to be revived by the best kind of animism.” —Richard Powers, author of The Overstory

“This autobiography of learning ways to heal the damaged earth and break the tightening grips of climate crisis offers a rational and inclusive way to keep our future.” —Annie Proulx, author of The Shipping News and Barkskins

- On Sale

- Oct 5, 2021

- Page Count

- 280 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781643261324

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use