Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

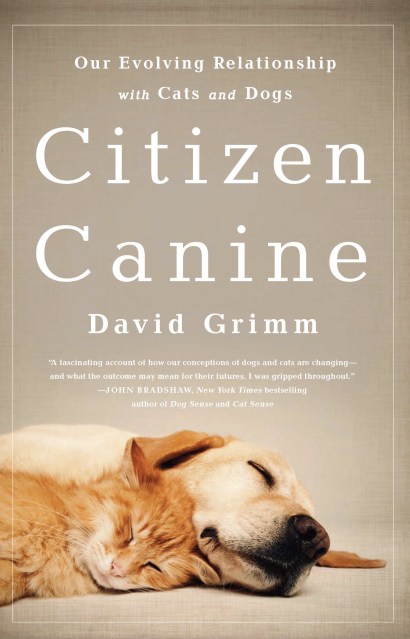

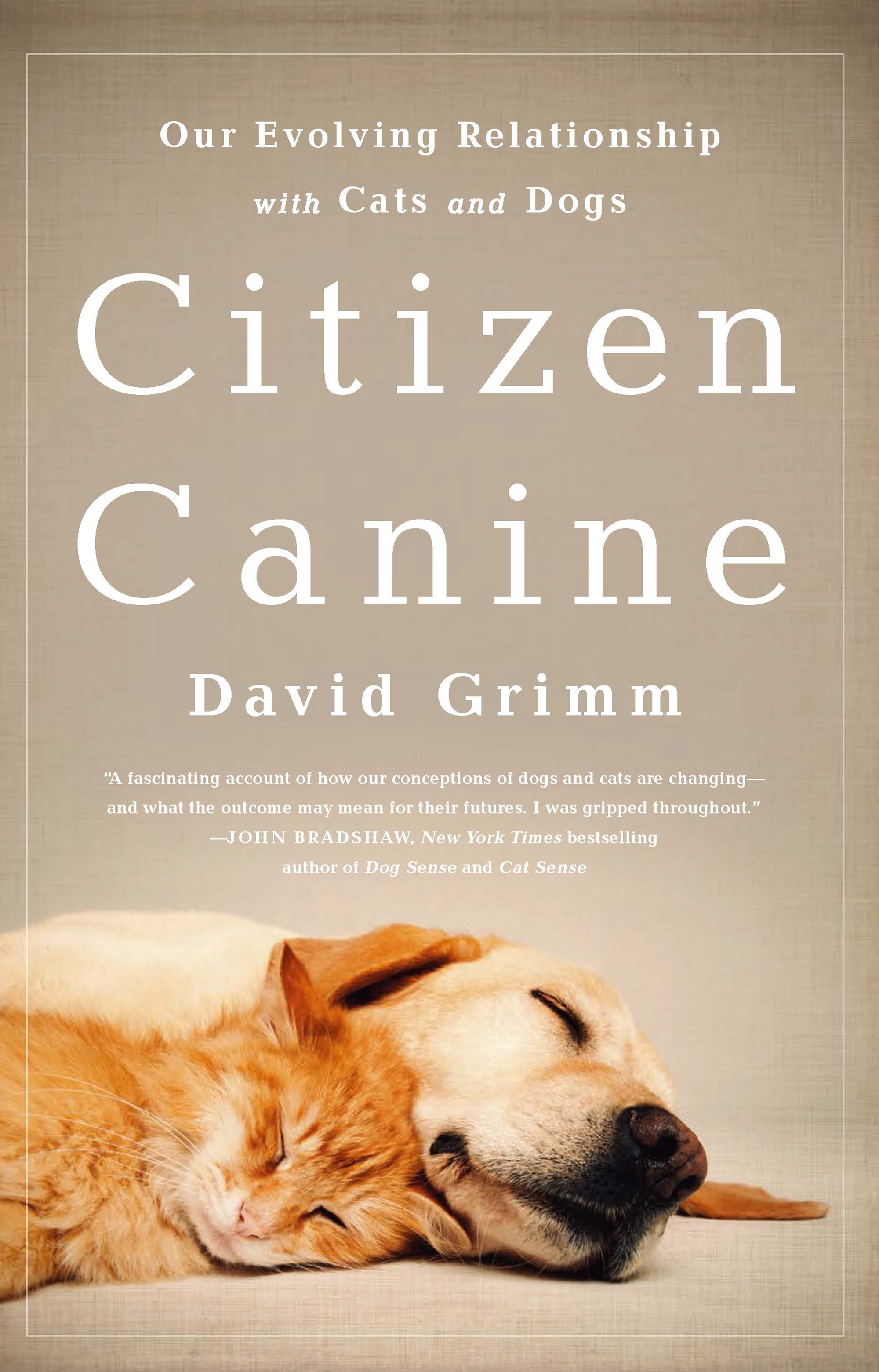

Citizen Canine

Our Evolving Relationship with Cats and Dogs

Contributors

By David Grimm

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 8, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Cats and dogs were once wild animals. Today, they are family members and surrogate children. A little over a century ago, pets didn’t warrant the meager legal status of property. Now, they have more rights and protections than any other animal in the country. Some say they’re even on the verge of becoming legal persons.

How did we get here — and what happens next?

In this fascinating exploration of the changing status of dogs and cats in society, pet lover and award-winning journalist David Grimm explores the rich and surprising history of our favorite companion animals. He treks the long and often torturous path from their wild origins to their dark days in the middle ages to their current standing as the most valued animals on Earth. As he travels across the country — riding along with Los Angeles detectives as they investigate animal cruelty cases, touring the devastation of New Orleans in search of the orphaned pets of Hurricane Katrina, and coming face-to-face with wolves and feral cats — Grimm reveals the changing social attitudes that have turned pets into family members, and the remarkable laws and court cases that have elevated them to quasi citizens.

The journey to citizenship isn’t a smooth one, however. As Grimm finds, there’s plenty of opposition to the rising status of cats and dogs. From scientists and farmers worried that our affection for pets could spill over to livestock and lab rats to philosophers who say the only way to save society is to wipe cats and dogs from the face of the earth, the battle lines are being drawn. We are entering a new age of pets — one that is fundamentally transforming our relationship with these animals and reshaping the very fabric of society.

For pet lovers or anyone interested in how we decide who gets to be a “person” in today’s world, Citizen Canine is a must read. It is a pet book like no other.

Genre:

-

“David Grimm brings a uniquely balanced perspective to a subject that is often overwrought with emotions: the modern relationship between pets and their people. Whether you are a devoted pet lover or a skeptical spouse, "Citizen Canine" is as entertaining as it is eye-opening.”—Ken Foster, bestselling author of The Dogs Who Found Me and I'm a Good Dog

“No one who loves cats and dogs should miss this book. Grimm tackles the tough questions of our times: Should cats and dogs, and other animals be regarded as persons? Would they be happier leading feral lives? Grab this book and read it now for some surprising and inspiring answers.”—Virginia Morell, author of Animal Wise, a Kirkus Reviews "Best Book of 2013"

“Grimm traces the evolution of today's pets, from once being considered feral beasts and valueless subjects to family members and quasicitizens. The author's research includes fascinating travels across the country interviewing detectives investigating animal cruelty cases, soldiers training military working dogs, and animal law attorneys, and he also visits a wolf sanctuary…Engrossing, enjoyable, and well-researched.”—Library Journal, starred -

“Grimm, deputy news editor at Science, investigates the ever-changing roles played by cats and dogs throughout history and travels the U.S. speaking to those on the cutting edge of animal science and welfare. [His] most valuable contribution…is his reasoned and well-researched discussion of the pet “personhood” movement, particularly its legal implications for veterinarians, scientific research, and agriculture.”—Publishers Weekly

"Our most common pets—cats and dogs—have made a long journey from wild animals to treasured family members. How did this transition happen? Science magazine editor and journalist Grimm explores the biological changes in cats and dogs as well as human laws and social attitudes in his broad survey of what our companion animals mean to us…Well researched and also very personable, this book will make readers think as they look into the eyes of those furry beings that share their lives.”—Booklist

“An arresting and valuable overview, it's packed with inspiration and imagination for our future relationship with our four-legged friends.”—Seattle Kennel Club

“Citizen Canine is an easy, enjoyable, must-read for all who want to know more about these fascinating beings.”—The Bark -

“An engaging account of how dogs and cats came to be our best friends."—Michiko Kakutani, New York Times

"A fascinating account of how our conceptions of dogs and cats are changing - and what the outcome may mean for their futures. I was gripped throughout."—John Bradshaw, New York Times bestselling author of Dog Sense and Cat Sense

“Well-researched, wide ranging, and well-written. A must read for those who share their lives with dogs and cats. You'll come to realize that our interactions with these animals are central to defining who we are.”—Marc Bekoff, author of The Emotional Lives of Animals and Why Dogs Hump and Bees Get Depressed

“CITIZEN CANINE is a fascinating journey through time and space, documenting our relationship with our closest domestic friends. Meticulously researched and brilliantly written, Grimm's work is relevant, not just to every dog and cat lover, but anyone interested in how we came to be the humans we are today.”

—Dr. Brian Hare, Associate Professor of Evolutionary Anthropology, Duke University, and author of the New York Times Bestseller, The Genius of Dogs

- On Sale

- Apr 8, 2014

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610391344

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use