Promotion

Use code FALL24 for 20% off sitewide!

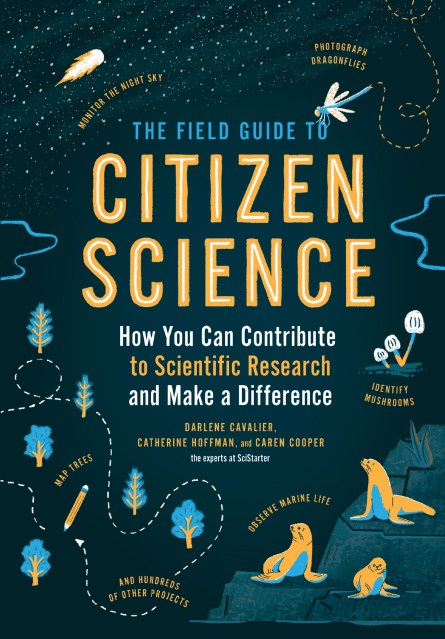

The Field Guide to Citizen Science

How You Can Contribute to Scientific Research and Make a Difference

Contributors

By Catherine Hoffman

By Caren Cooper

Formats and Prices

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $16.95 $22.95 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 4, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Learn how monitoring the night sky, mapping trees, photographing dragonflies, and identifying mushrooms can help save the world.

Citizen science is the public involvement in the discovery of new scientific knowledge. A citizen science project can involve one person or millions of people collaborating towards a common goal. It is an excellent option for anyone looking for ways to get involved and make a difference. The Field Guide to Citizen Science, from the expert team at SciStarter, provides everything you need to get started. You’ll learn what citizen science is, how to succeed and stay motivated when you’re participating in a project, and how the data is used. The fifty included projects, ranging from climate change to Alzheimer’s disease, endangered species to space exploration, mean sure-fire matches for your interests and time. Join the citizen science brigade now and start making a real difference!

-

“Writing with encouraging clarity, the authors explain how to become a citizen scientist and how scientists provide the instructions and equipment required for collecting authentic data.” —Booklist

“The most powerful way for science to change your perception of the world is for you to do it yourself. That's the underlying theme of this friendly how-to overview of the citizen science movement… As with every great adventure, you just have to take the first step to get going.” —Discover Magazine

“This book is infectious in the best way possible. In a world that often feels like it is spinning out of control, where your actions can appear insignificant and change seems out-of-reach, this book gives you hope, a sense of possibility, and perhaps even a purpose.” —Science Connected

“A must-have resource for learning the truths and myths of citizen science.” —The Arlington Daily Herald

- On Sale

- Feb 4, 2020

- Page Count

- 188 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781604699807

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use