By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

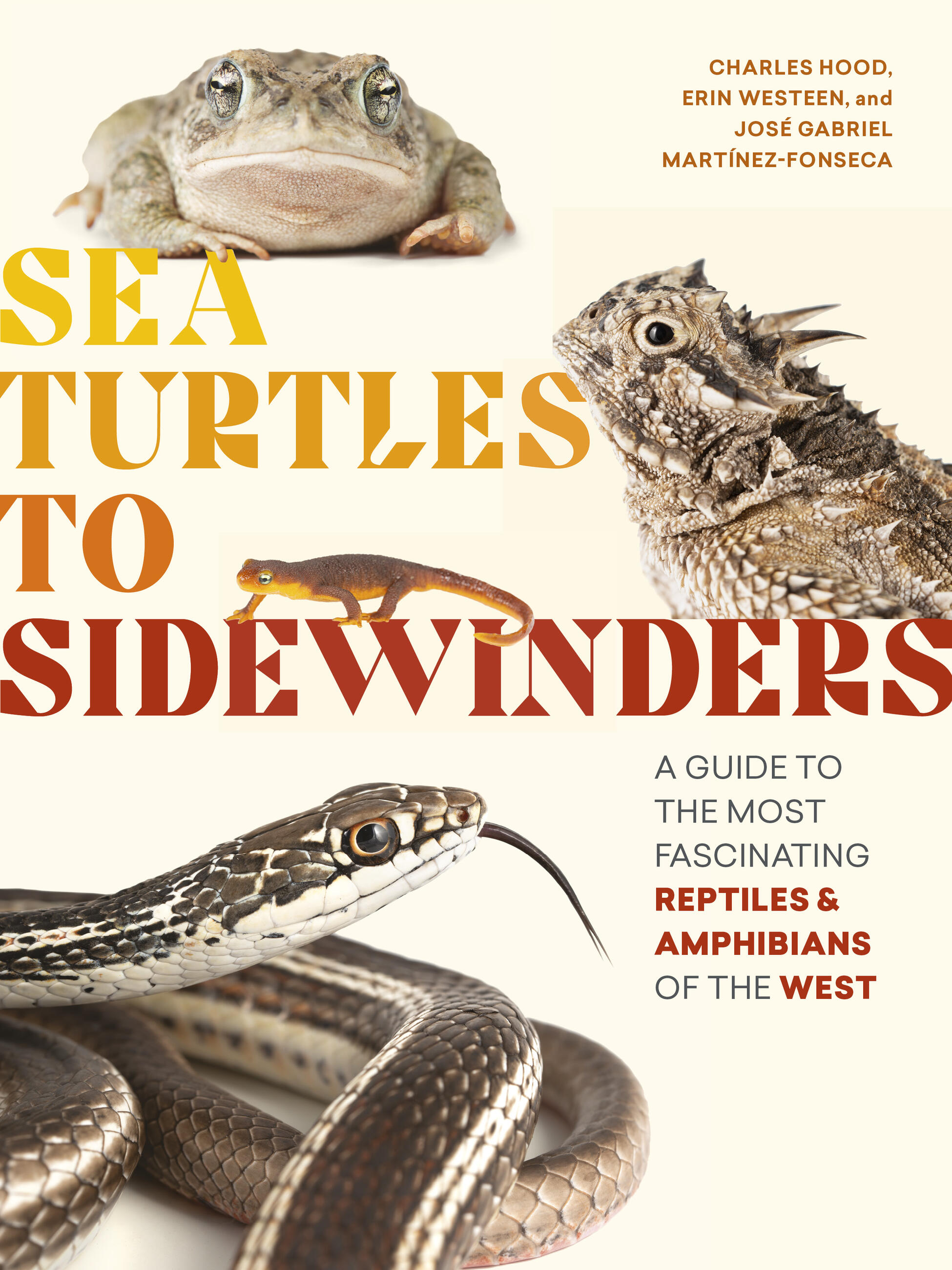

Sea Turtles to Sidewinders

A Guide to the Most Fascinating Reptiles and Amphibians of the West

Contributors

By Charles Hood

By Erin Westeen

By Jose Gabriel Martinez-Fonseca

Formats and Prices

Price

$19.95Price

$24.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.95 $24.95 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 15, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

"For families wanting to explore their local wildlife as well as an engaging read for those with a general interest in the subject.” —Booklist

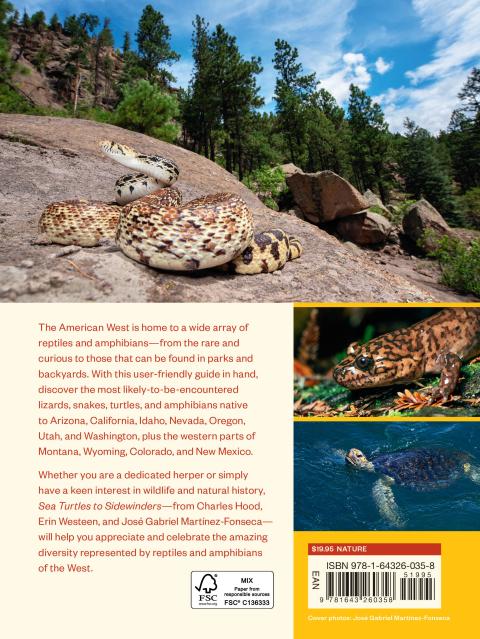

The American West is home to a wide array of reptiles and amphibians-from the rare and curious to those that can be found in parks and backyards. With this user-friendly guide in hand, discover the most likely-to-be-encountered lizards, snakes, turtles, and amphibians native to Arizona, California, Idaho, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, and Washington, plus the western parts of Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico.

Whether you are a dedicated herper or simply have a keen interest in wildlife and natural history, Sea Turtles to Sidewinders—from Charles Hood, Erin Westeen, and Jose Gabriel Martfnez-Fonsec—will help you appreciate and celebrate the amazing diversity represented by reptiles and amphibians of the West.

- On Sale

- Feb 15, 2022

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781643260358

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use