Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

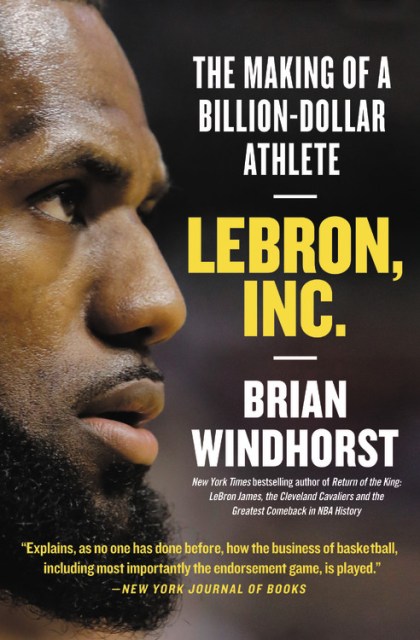

LeBron, Inc.

The Making of a Billion-Dollar Athlete

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 7, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

With eight straight trips to the NBA Finals, LeBron James has proven himself one of the greatest basketball players of all time. And like Magic Johnson and Michael Jordan before him, LeBron has also become a global brand and businessman who has altered the way professional athletes think about their value, maximize their leverage, and use their voice.

LEBRON, INC tells the story of James’s journey down the path to becoming a billionaire sports icon — his successes, his failures, and the lessons both have taught him along the way. With plenty of newsmaking tidbits about his rollercoaster last season in Cleveland and high-profile move to the Lakers, LEBRON, INC. shows how James has changed the way most elite athletes manage their careers, and how he launched a movement among his peers that may last decades beyond his playing days.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 7, 2020

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538730850

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use