By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

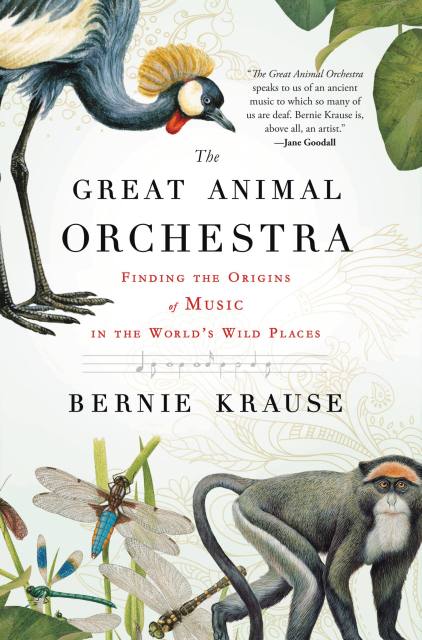

The Great Animal Orchestra

Finding the Origins of Music in the World's Wild Places

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 19, 2012

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316192392

Price

$8.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $8.99 $11.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 19, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A “passionate amalgam of science and autobiography” that will leave you hearing — and seeing — nature as never before (New York Times Book Review).

Musician and naturalist Bernie Krause is one of the world’s leading experts in natural sound, and he’s spent his life discovering and recording nature’s rich chorus. Searching far beyond our modern world’s honking horns and buzzing machinery, he has sought out the truly wild places that remain, where natural soundscapes exist virtually unchanged from when the earliest humans first inhabited the earth.

Krause shares fascinating insight into how deeply animals rely on their aural habitat to survive and the damaging effects of extraneous noise on the delicate balance between predator and prey. But natural soundscapes aren’t vital only to the animal kingdom; Krause explores how the myriad voices and rhythms of the natural world formed a basis from which our own musical expression emerged.

From snapping shrimp, popping viruses, and the songs of humpback whales — whose voices, if unimpeded, could circle the earth in hours — to cracking glaciers, bubbling streams, and the roar of intense storms; from melody-singing birds to the organlike drone of wind blowing over reeds, the sounds Krause has experienced and describes are like no others. And from recording jaguars at night in the Amazon rain forest to encountering mountain gorillas in Africa’s Virunga Mountains, Krause offers an intense and intensely personal narrative of the planet’s deep and connected natural sounds and rhythm.

The Great Animal Orchestra is the story of one man’s pursuit of natural music in its purest form, and an impassioned case for the conservation of one of our most overlooked natural resources-the music of the wild.

Genre:

-

Featured in The New York Times Book Review's Paperback Row

-

"The Great Animal Orchestra is about the symphony of beasts that surrounds us, a vast orchestra in the process of being silenced....A fascinating life, and devotion to a fascinating topic...Krause wakes up your ears, gives you a desire to experience these wild soundscapes." -- Jeremy Denk, New York Times Book Review

-

"Forty years travelling the world to record more than 15,000 species have given Krause a rare insight into the importance of 'biophony'." -- Nature

-

"This passionate amalgam of science and autobiography argues that in the wild, animals vocalize with a musicianly ear." -- New York Times Editors' Choice

-

"Krause...has recorded the sounds of more than 15,000 animal species and their natural ambience. This often poetic and thoroughly entertaining book reflects his passion." -- San Francisco Chronicle

-

"The Great Animal Orchestra speaks to us of an ancient music to which so many of us are deaf. Bernie Krause is, above all, an artist. I have watched him recording the calls of chimpanzees, the singing of the insects and birds, and seen his deep love for the harmonies of nature. In this book he helps us to hear and appreciate the often hidden musicians in a new way. But he warns that these songs, an intrinsic part of the natural world and essential to human well being, are vanishing, one by one, snuffed out by human actions. Read The Great Animal Orchestra, tell your friends about it. And as Bernie urges, let us all do our part to preserve the age old sounds of nature." -- Jane Goodall

-

"This fascinating book awakens our ancient ears to the source of all music. Read it, and you'll yearn to muffle our din-and hear anew." -- Alan Weisman, author of THE WORLD WITHOUT US

-

"Bernie Krause and his niche theory are the real thing. His originality, research, and above all basic knowledge of the sound environments in nature are impressive. The idea of music originating in the sound communication systems of wild animals is a sound and provocative hypothesis. I admire also his attention to the preservation of ancestral-level cultures for their own value but also as a testing ground for theory on human behavioral evolution." -- E.O. Wilson

-

"Krause always reveals wondrous stories of the meaning of music and sounds of our natural environment. Bernie's research into the subtleties of animal and insect sounds is unparalleled, but it is his description of the radical changes that are taking place on this planet that really makes on stop and wonder... Listen carefully, for the sounds you hear may never be the same again." -- Sir George Martin

-

"Krause shows us the music of the natural world - long may his work continue!" -- Pete Seeger

-

"Bernie Krause has admirably produced not only a comprehensive overview of the art of nature recording, but also shows his heartfelt understanding and appreciation of natural soundscapes, a threatened heritage in our modern world." -- Dr. Roger Payne, author of Songs of the Humpback Whale

-

"This book will get you to wake up and listen to the natural world." -- San Francisco Chronicle

-

"If a picture is worth a thousand words, what is a sound recording worth? Perhaps much more... We say we want peace and quiet, but Bernie knows better. What we really want is something worth listening to. There is plenty of it out there. Nobody knows how to find it better than Bernie Krause." -- Jean Michel Cousteau

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

Introduction

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine (Coda)

Praise

-

Featured in The New York Times Book Review’s Paperback Row

-

“The Great Animal Orchestra is about the symphony of beasts that surrounds us, a vast orchestra in the process of being silenced….A fascinating life, and devotion to a fascinating topic…Krause wakes up your ears, gives you a desire to experience these wild soundscapes.” — Jeremy Denk, New York Times Book Review

-

“Forty years travelling the world to record more than 15,000 species have given Krause a rare insight into the importance of ‘biophony’.” — Nature

-

“This passionate amalgam of science and autobiography argues that in the wild, animals vocalize with a musicianly ear.” — New York Times Editors’ Choice

-

“Krause…has recorded the sounds of more than 15,000 animal species and their natural ambience. This often poetic and thoroughly entertaining book reflects his passion.” — San Francisco Chronicle

-

“The Great Animal Orchestra speaks to us of an ancient music to which so many of us are deaf. Bernie Krause is, above all, an artist. I have watched him recording the calls of chimpanzees, the singing of the insects and birds, and seen his deep love for the harmonies of nature. In this book he helps us to hear and appreciate the often hidden musicians in a new way. But he warns that these songs, an intrinsic part of the natural world and essential to human well being, are vanishing, one by one, snuffed out by human actions. Read The Great Animal Orchestra, tell your friends about it. And as Bernie urges, let us all do our part to preserve the age old sounds of nature.” — Jane Goodall

-

“This fascinating book awakens our ancient ears to the source of all music. Read it, and you’ll yearn to muffle our din-and hear anew.” — Alan Weisman, author of THE WORLD WITHOUT US

-

“Bernie Krause and his niche theory are the real thing. His originality, research, and above all basic knowledge of the sound environments in nature are impressive. The idea of music originating in the sound communication systems of wild animals is a sound and provocative hypothesis. I admire also his attention to the preservation of ancestral-level cultures for their own value but also as a testing ground for theory on human behavioral evolution.” — E.O. Wilson

-

“Krause always reveals wondrous stories of the meaning of music and sounds of our natural environment. Bernie’s research into the subtleties of animal and insect sounds is unparalleled, but it is his description of the radical changes that are taking place on this planet that really makes on stop and wonder… Listen carefully, for the sounds you hear may never be the same again.” — Sir George Martin

-

“Krause shows us the music of the natural world – long may his work continue!” — Pete Seeger

-

“Bernie Krause has admirably produced not only a comprehensive overview of the art of nature recording, but also shows his heartfelt understanding and appreciation of natural soundscapes, a threatened heritage in our modern world.” — Dr. Roger Payne, author of Songs of the Humpback Whale

-

“This book will get you to wake up and listen to the natural world.” — San Francisco Chronicle

-

“If a picture is worth a thousand words, what is a sound recording worth? Perhaps much more… We say we want peace and quiet, but Bernie knows better. What we really want is something worth listening to. There is plenty of it out there. Nobody knows how to find it better than Bernie Krause.” — Jean Michel Cousteau