Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

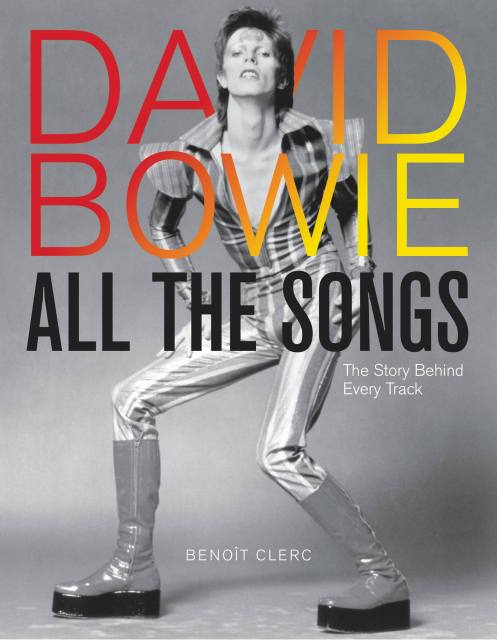

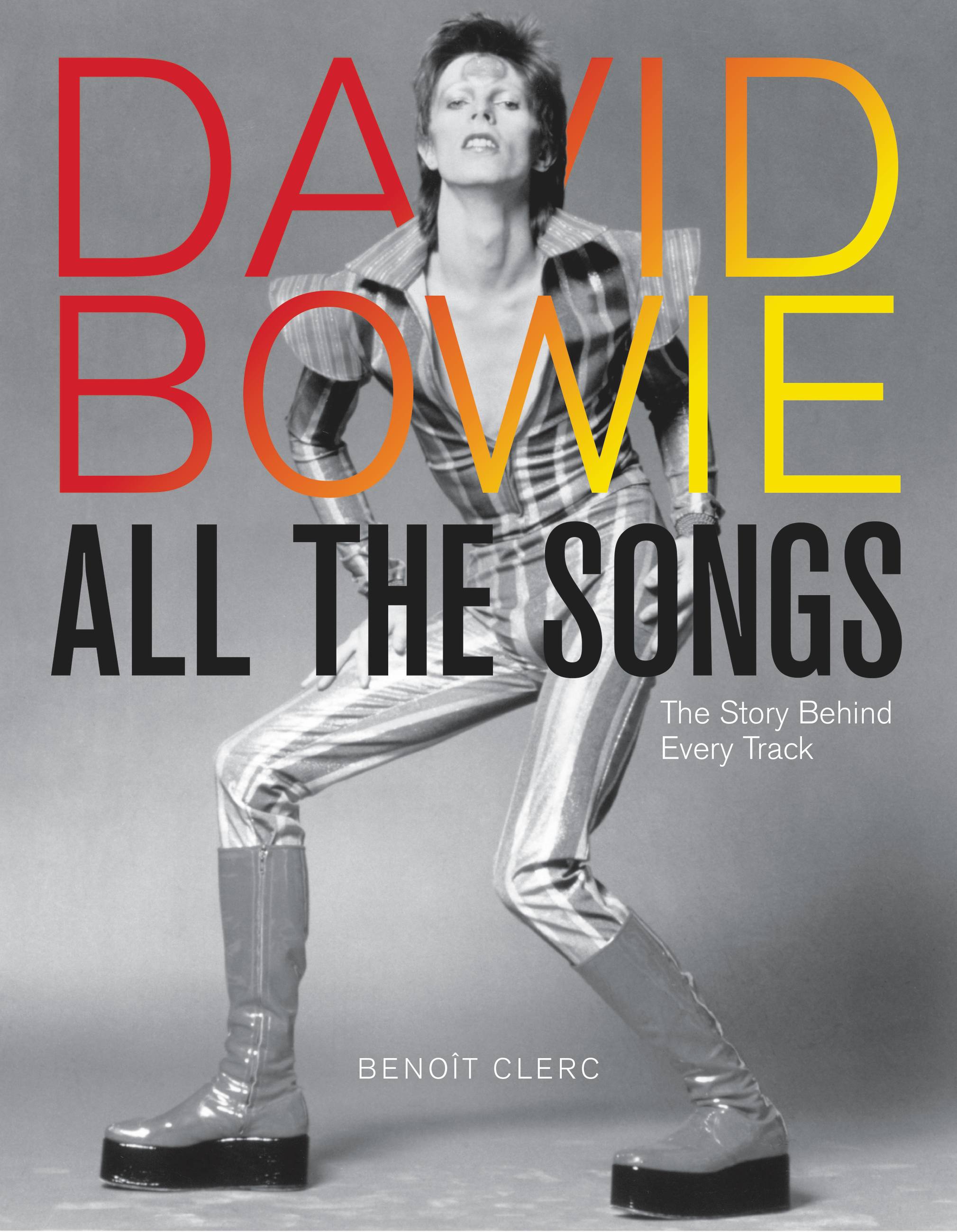

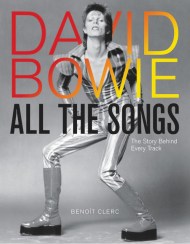

David Bowie All the Songs

The Story Behind Every Track

Contributors

By Benoît Clerc

Formats and Prices

Price

$35.99Price

$46.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $35.99 $46.99 CAD

- Hardcover $55.00 $70.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 5, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A lovingly thorough dissection of every album and every track ever released by David Bowie over the span of his nearly 50 year career, David Bowie All the Songs follows the musician from his self-titled debut album released in 1967 all the way through Blackstar, his final album.

Delving deep into Bowie's past and featuring new commentary and archival interviews with a wide range of models, actors, musicians, producers, and recording executives who all worked with and knew the so-called "Thin White Duke", David Bowie All the Songs charts the musician's course from a young upstart in 1960s London to a musical behemoth who collaborated with everyone from Queen Latifah and Bing Crosby, to Mick Jagger and Arcade Fire.

This one-of-a-kind book draws upon years of research in order to recount how each song was written, composed, and recorded, down to the instruments used and the people who played them. Featuring hundreds of vivid photographs that celebrate one of music's most visually arresting performers, David Bowie All the Songs is a must-have book for any true fan of classic rock.

Genre:

Series:

- On Sale

- Apr 5, 2022

- Page Count

- 624 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780762474721

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use