Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

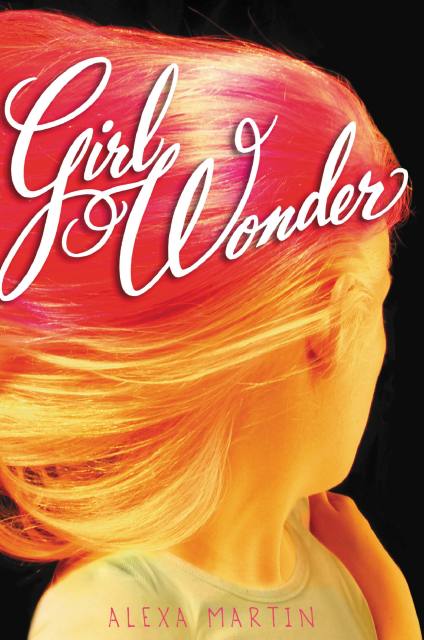

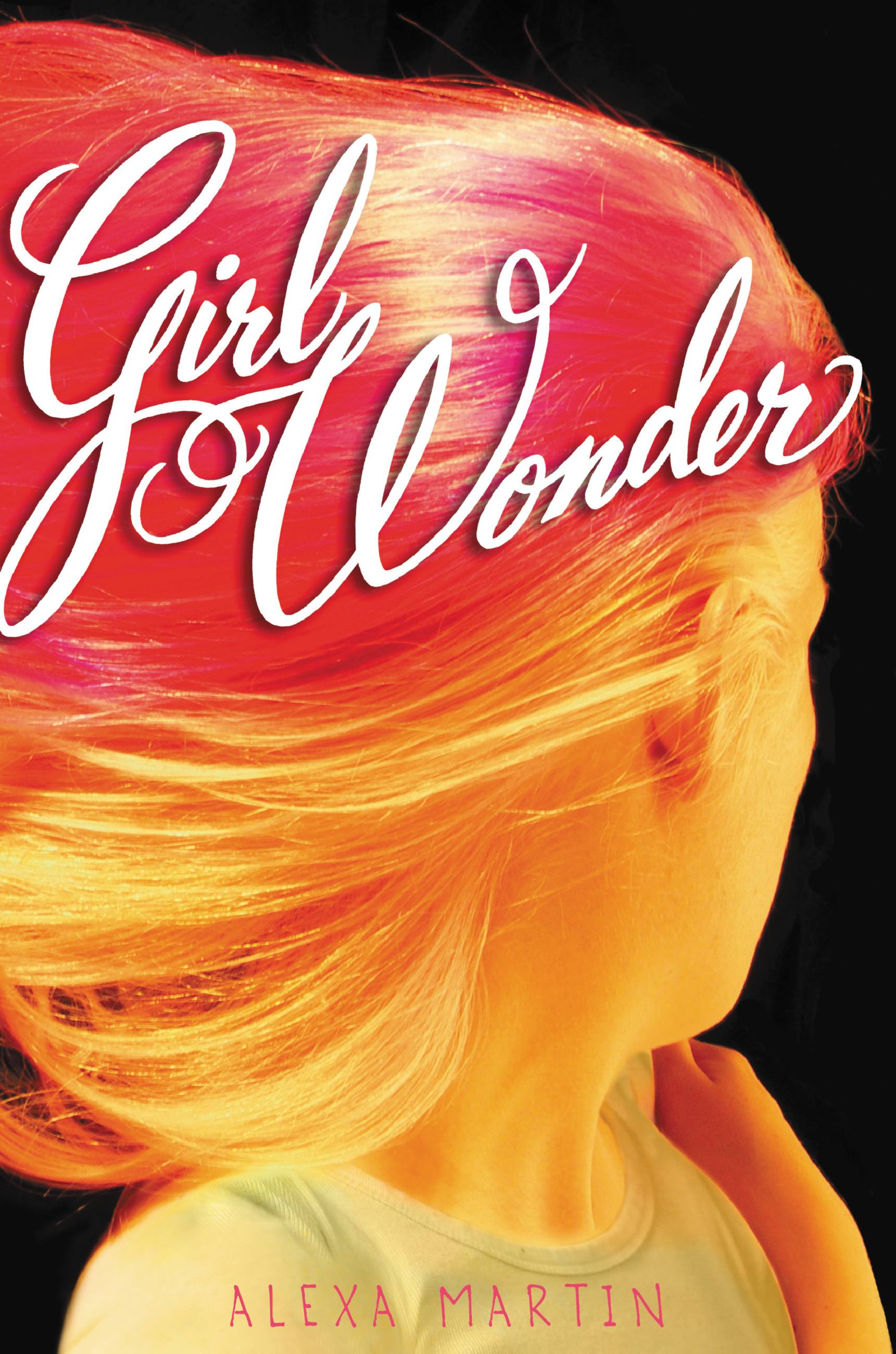

Girl Wonder

Contributors

By Alexa Martin

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $9.99 $12.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 4, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Then Amanda enters her orbit like a hot-pink meteor, offering Charlotte a ticket to popularity. Amanda is fearless, beautiful, and rich. As her new sidekick, Charlotte is brought into the elite clique of the debate team-and closer to Neal, the most perfect boy she has ever seen.

Senior year is finally looking up. . . .or is it? The more things heat up between Charlotte and Neal, the more he wants to keep their relationship a secret. Is he ashamed? Meanwhile, Amanda is starting to act strangely competitive. Could Charlotte’s new BFF be hiding something?

A riveting debut novel full of magnetic characters, romantic intrigue, and dark humor, Girl Wonder is a poignant story of first love, jealousy, and friendship that will keep readers rooting for Charlotte until the very end.

- On Sale

- May 4, 2011

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9781423152460

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use