Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

The Constitution Today

Timeless Lessons for the Issues of Our Era

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.99 $38.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 13, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

America’s Constitution, Chief Justice John Marshall famously observed in McCulloch v. Maryland, aspires “to endure for ages to come.” The daily news has a shorter shelf life, and when the issues of the day involve momentous constitutional questions, present-minded journalists and busy citizens cannot always see the stakes clearly.

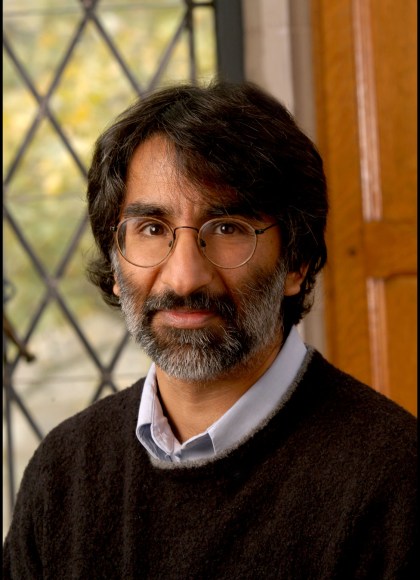

In The Constitution Today, Akhil Reed Amar, America’s preeminent constitutional scholar, considers the biggest and most bitterly contested debates of the last two decades and provides a passionate handbook for thinking constitutionally about today’s headlines. Amar shows how the Constitution’s text, history, and structure are a crucial repository of collective wisdom, providing specific rules and grand themes relevant to every organ of the American body politic. Prioritizing sound constitutional reasoning over partisan preferences, he makes the case for diversity-based affirmative action and a right to have a gun in one’s home for self-protection, and against spending caps on independent political advertising and bans on same-sex marriage. He explains what’s wrong with presidential dynasties, advocates a “nuclear option” to restore majority rule in the Senate, and suggests ways to reform the Supreme Court. And he revisits three dramatic constitutional conflicts — the impeachment of Bill Clinton, the contested election of George W. Bush, and the fight over Barack Obama’s Affordable Care Act — to show what politicians, judges, and journalists got right as events unfolded and what they missed.

Leading readers through the particular constitutional questions at stake in each episode while outlining his abiding views regarding the Constitution’s letter, its spirit, and the direction constitutional law must go, Amar offers an essential guide for anyone seeking to understand America’s Constitution and its relevance today.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 13, 2016

- Page Count

- 464 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465096343

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use