Five Reasons to Use Biochar in Your Garden

Every savvy gardener knows that your garden is only as good as the soil it’s grown in. While biochar isn’t nutrient-rich in its own right, it is a simple and very effective way to bring your garden soil to its full health and growing potential.

We’ve known for years that plants communicate with one another through their roots and the networks of soilborne fungi that colonize them. But scientists are only now discovering that those connections are just the tip of the iceberg. We may sit quietly and enjoy the peace of nature in our gardens and local woodlands, but above, around, and below us, the natural world is humming with almost infinite activity. Think of Manhattan Island made of living tissue. Truth be told, our gardens and landscapes share in the thunderous communications systems buzzing in their biology, especially in the webs of fungal mycelia that carry messages among plants.

The natural ecosystems facilitated by these communications systems are the key to a healthy soil, because they increase its biodiversity. The more life forms, the more the food sources available are utilized, and the more complex and stronger is the web of life.

Biochar is organic matter that has been roasted (pyrolyzed) at temperatures above 660°F (350°C) with very limited oxygen. Just about any organic matter — any plant or animal that was once alive — can be used as the raw material, also called feedstock, but plant material in general and wood in particular is preferred.

On the surface, it might be difficult to see how biochar could be beneficial for the soil. It isn’t a nutrient or food source for microbes or plants. Biochar doesn’t dissolve in water. It doesn’t degrade as quickly as uncharred organic matter. So if biochar isn’t a fertilizer, what is it?

Biochar …

… is a housing complex for microbes.

In pyrolysis, combustion is reduced by restricting airflow to the organic matter once it is actively burning. Heating the feedstock with very little air roasts it, rather than burns it, preserving the structure of the material down to the microscopic level. If you looked through a microscope, you’d see that a fragment of biochar made from wood is porous and consists of empty chambers. These chambers are the remnants of the xylem and phloem vessels — the channels by which once-living plants took up and delivered water and nutrients to the leaves.

Among these now-empty phloem and xylem tubules are large spaces. These “rooms” are adsorbent, holding water, oils, sugars, proteins, and other substances produced by the beneficial soil microbes that occupy them. These interior spaces also provide safe hiding places for these microbes that do so much of the work to feed and support the health of the plants with which they are growing.

… is a reservoir for water and nutrients.

Besides providing housing to soil creatures, biochar’s tubules, when in the hydrophilic state, draw in water and nutrients through capillary action. The water is then metered out to plants as needed, giving biochar-amended soils a drought tolerance they may not otherwise have. The nutrients not only feed plant roots but also feed the microbes living in the biochar housing complexes. The combined effect of better water-holding capacity and proliferation of soil life gives biochar-amended soils lightness and a natural fine tilth that plants love.

… boosts plants’ ability to take up nutrients.

While the interior structure of biochar increases the water-holding capacity of the soil, its surface acts as a reservoir for nutrients. This is one of its most important benefits for plants.

Most biochar is carbon in its stable ring form, which captures photons, electrons, and a range of ions. Because biochar was once living plant tissue, it contains more than just carbon. It also contains minerals like magnesium, potassium, iron, and manganese — positively charged plant nutrients that are called cations. Because these elements and others in the biochar carry a positive charge, they are attracted to the negatively charged surfaces of the biochar. This activity isn’t strong enough to form chemical bonds. Rather, it holds the minerals in a loose aggregation on or near the charged sites until needed to feed plant roots. This is called the cation exchange capacity (CEC) of the soil, and it has great importance for the way rich, organic, biochar-amended soils feed and support plants.

Often embedded in the carbon of the biochar are compounds that can react to create anions, negatively charged ions. One of the most important anions that feed plants is phosphate, and phosphorous can adhere to biochar’s surfaces. This reduces the amount of nutrients that leach out of the soil during rains or by irrigation.

… decreases greenhouse gases.

Another benefit of adding biochar to your soil is that its carbon will not be released as quickly as greenhouse gas. If more carbon is stored in the soil, it reduces the amount present in the atmosphere and thus reduces global warming. The process of storing carbon in soil is called soil carbon sequestration. Because of its properties, biochar doesn’t enter the chain of decomposition the way, say, decomposing cornstalks do. The natural flux of carbon through decomposition of those cornstalks ends up with a significant amount of the carbon being released as carbon dioxide — a greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change. If those cornstalks (or any other organic matter) are pyrolyzed, that very stable form of carbon will stay sequestered in the soil for centuries, and the emission of carbon dioxide can be reduced dramatically — by up to 90 percent.

Biochar also reduces the formation and outgassing of nitrous oxide, another greenhouse gas.

It is true that the combustion of any biomass — wood, straw, leaves, weeds, and so on — releases methane, a gas that’s 20 times more potent than carbon dioxide as a greenhouse gas. But the process of pyrolysis burns off methane emissions as air is allowed into a combustion chamber, helping retard the emissions of methane.

… buffers the effects of toxic elements.

Biochar can reduce the toxic effects of heavy metals in soils and in some plants grown in those soils. In one study, copper, manganese, mercury, lead, cadmium, chromium, and zinc, as well as arsenic compounds, all became less bioavailable in green beans when the beans were grown in biochar-amended soils, compared to those grown in soils not amended with biochar. We’ve known for years that soils rich in organic matter can reduce the uptake of toxins into garden crops; biochar adds another level of protection for gardeners who may not know they have toxic heavy metals in their soil.

Biochar supports enhances the mechanical and biological processes that make for great gardens. When you use it in the garden, you are seeding fertility in the soil that will last far down the corridors of time, leaving a healthy source of soil and food for generations to come.

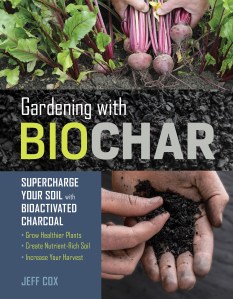

Text excerpted from Gardening with Biochar © Jeff Cox.

In this highly accessible handbook, long-time garden writer Jeff Cox explains what biochar is and provides detailed instructions for how it can be made from wood or other kinds of plant material, along with specific guidelines for using it to enrich soil, prevent erosion, and enhance plant growth. Now widely available at garden centers, biochar is also being lauded for its ability to sequester carbon in the soil, making it good for the health of the planet as well as the plants.