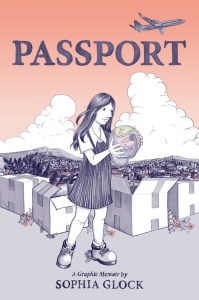

Sophia Glock on Passport

I’ve been writing comics in earnest for fifteen years I’ve always felt they are an ideal medium for memoir and there is a long history of auto-biographical comics which bears this out. Comics are visual and visceral, which encourages the brutal vulnerability required of a memoirist. Yet, before this book, I avoided drawing personal stories, just like I avoided telling certain stories to friends.

I’m not by nature a secretive person. If anything, I’m an over sharer. But there were a few stories, especially ones around my childhood, that elicited too many awkward questions. I taught myself a script to repeat about my background, one I developed over the years with tips from my parents: deflect, volley back questions, change the subject, tell partial truths. So even though I loved the raw autobiographical comics of Alison Bechdel and Marjane Satrapi, I avoided sharing my own experiences. When I did try to tell these stories, they felt stilted. The voice always came out flat, didactic, and too knowing. I shelved these attempts at talking about myself and instead I wrote about fairytales, about magic, about girls in towers. I wrote about dreams and monsters, even while the people closest to me gently suggested that some of what I had been through rivaled the fantastical details of the stories I was making up. I knew they were right, that as a comics writer I should at least try to explore my uncommon upbringing, but I had no idea how to reconcile a memoirist’s duty to tell the truth with my discomfort at discussing family secrets.

A single memory unlocked Passport for me. One day I placed a bar of chocolate in my new nightstand, in my new apartment, in my new city. I had just married and was starting a new chapter of my life, surrounded by the novelty of what was supposed to be my adulthood, and I realized in this chocolate bar, this drawer, was a rare moment of continuity which linked me to my past. It linked me to my mother, who also kept chocolate in her nightstand. I was intimately aware of her habit of storing Godiva at her bedside because as a young girl I rifled through it whenever I could, searching for an illicit treat. I didn’t just steal chocolate of course, I was also spying on her, a delicious irony considering how the act of spying defined my mother’s life.

This flashback prompted a short comic. When I finished it I realized I had discovered the voice that would allow me to write the story I had been dancing around for so long. I finally found the voice of my younger self, the voice of a young girl who senses there is more to her own reality, but does not yet know what that is; the voice of a person in a liminal state, right before the veil lifts. With this voice I had found my way in. All I had to do was listen to this girl and she would show me how to write about my childhood. Her voice was my truth, and I now knew I could write the book that would become Passport.

I am still uncomfortable discussing the details of my parents’ careers, in as much I know what they were. But the central fact of my book, and my family’s life, was that they worked, covertly, in intelligence. Their lives were organized around the collection of secret information. Their work was secret, their currency was secrets. That culture of secrecy extended into our family life. Having what many would colloquially refer to as “spies” for parents meant that I was exposed to the nature of spying from infancy. They were at once acute observers of their children, eliciting information from us we would have happily kept to ourselves, while simultaneously modeling their trade: how to observe and obfuscate. They taught us how to uncover what is hidden while hiding the most important parts of yourself. It is a certain splitting of self. It is also a way of life.

Writing memoir is difficult, because you are trying to relay a time when you had little perspective on your life, but when writing you can’t forget what you’ve learned. The very premise of my book, being the child of parents who worked in intelligence, prepared me for this task. My parents’ work and lives were indistinguishable. The practice of observation, of soliciting personal crucial information from unsuspecting targets, was something they carried into all of their waking moments. As an adolescent I mirrored this skill set to my advantage. Later, when I returned to my high school years to write about them, those skills came in handy once more. The ability to detach, analyze, observe, and record made me the artist I am today and made the writing of Passport possible.

Although the premise of my book relies on the exceptional nature of my childhood, the process of observation, revelation, and self-actualization is not exceptional at all. We all must face the secrets of our families and communities. What we do with that information takes us on the path of finding out who we are. As an adolescent, I often felt displaced and compelled to find my place in the world, but that is not unique to my experience. We all must come to terms with our own origins, but our families are not our fates. Our place in the world is determined not only by what we are given, but by what we reject, and perhaps most importantly by what we choose to take with us into our own future.

Young Sophia has lived in so many different countries, she can barely keep count. Stationed now with her family in Central America because of her parents’ work, Sophia feels displaced as an American living abroad, when she has hardly spent any of her life in America.

Everything changes when she reads a letter she was never meant to see and uncovers her parents’ secret. They are not who they say they are. They are working for the CIA. As Sophia tries to make sense of this news, and the web of lies surrounding her, she begins to question everything. The impact that this has on Sophia’s emerging sense of self and understanding of the world makes for a page-turning exploration of lies and double lives.

In the hands of this extraordinary graphic storyteller, this astonishing true story bursts to life.