Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

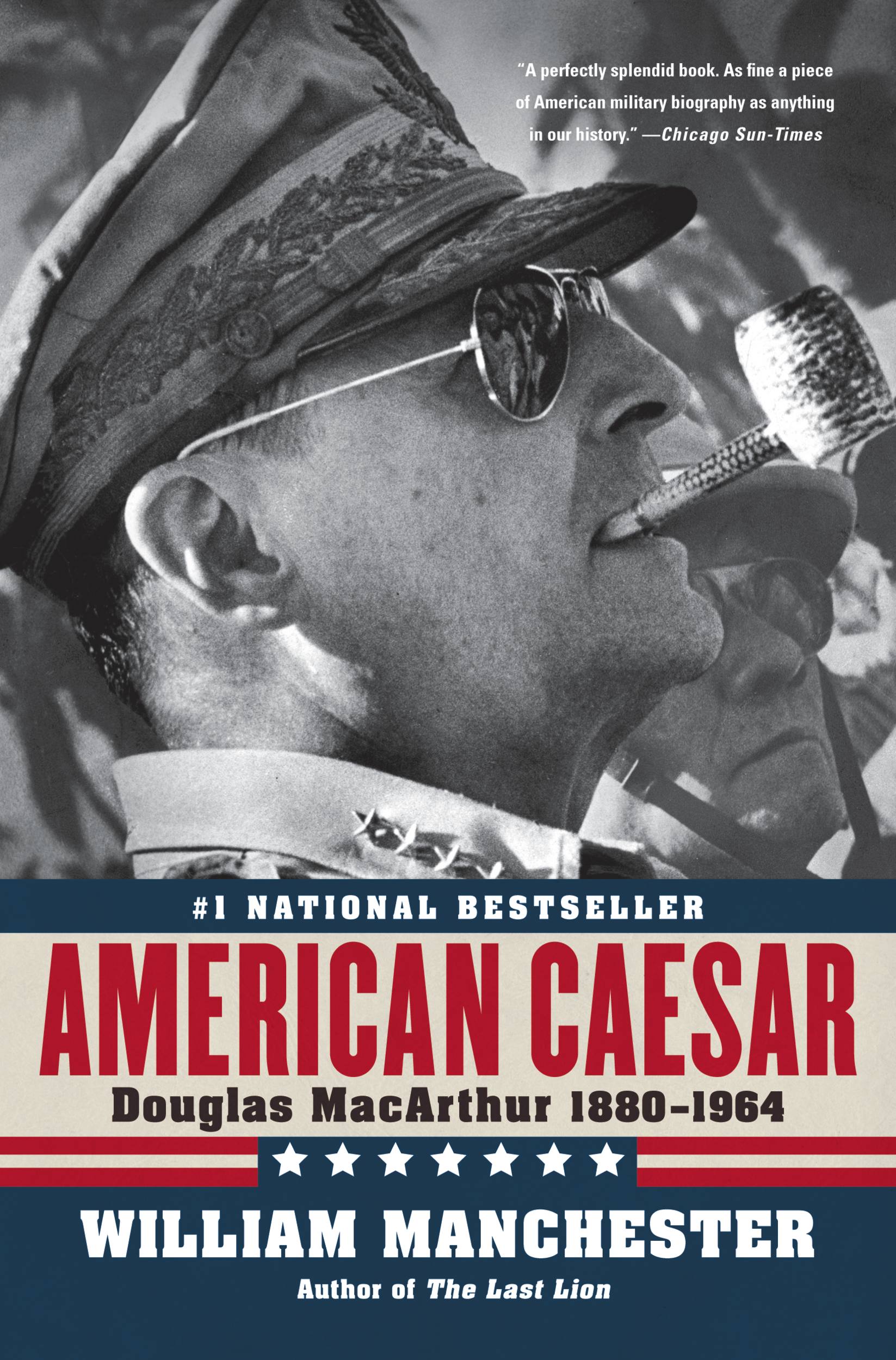

American Caesar

Douglas MacArthur 1880 - 1964

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $42.00 $53.00 CAD

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $30.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 12, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The bestselling classic that indelibly captures the life and times of one of the most brilliant and controversial military figures of the twentieth century.

“Electric…Tense with the feeling that this is the authentic MacArthur…Splendid reading.” — New York Times

American Caesar examines the exemplary army career, the stunning successes (and lapses) on the battlefield, and the turbulent private life of the soldier-hero whose mystery and appeal created a uniquely American legend.

Genre:

- On Sale

- May 12, 2008

- Page Count

- 816 pages

- Publisher

- Back Bay Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316032421

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use