Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

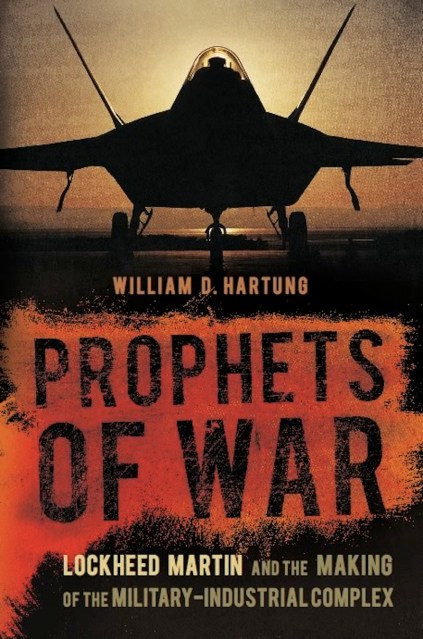

Prophets of War

Lockheed Martin and the Making of the Military-Industrial Complex

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 28, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

As a full-service weapons maker, Lockheed Martin receives over 25 billion per year in Pentagon contracts. From aircraft and munitions, to the abysmal Star Wars missile defense program, to the spy satellites that the NSA has used to monitor Americans’ phone calls without their knowledge, Lockheed Martin’s reaches into all areas of US defense and American life. William Hartung’s meticulously researched history follows the company’s meteoric growth and explains how this arms industry giant has shaped US foreign policy for decades.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Dec 28, 2010

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568586502

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use