Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

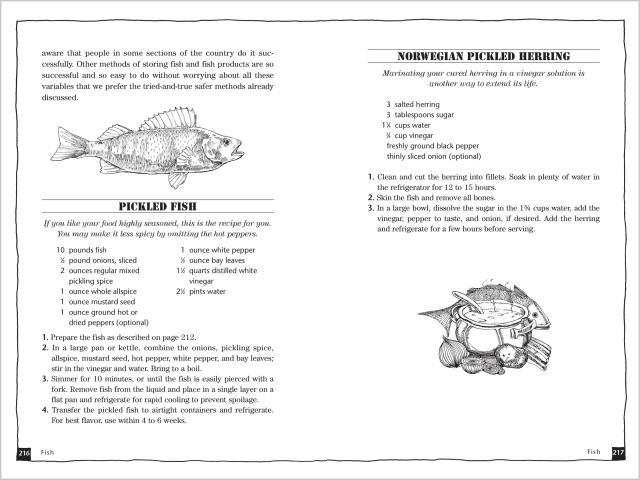

A Guide to Canning, Freezing, Curing & Smoking Meat, Fish & Game

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.95Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.95 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 15, 2002. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Preserve your meat properly and enjoy unparalleled flavor when you’re ready to eat it. This no-nonsense reference book covers all the major meat preserving techniques and how to best implement them. You’ll learn how to corn beef, pickle tripe, smoke sausage, cure turkey, and much more, all without using harsh chemicals. You’ll soon be frying up delicious homemade bacon for breakfast and packing your travel bag with tender jerky for snack time.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Aug 15, 2002

- Page Count

- 192 pages

- Publisher

- Storey

- ISBN-13

- 9781580174572

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use