Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

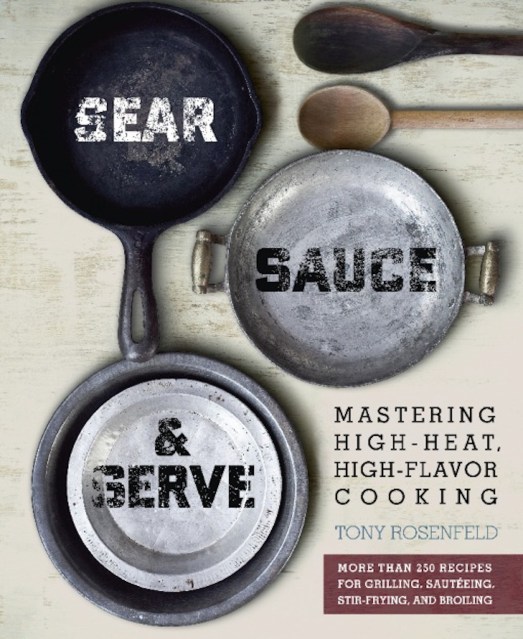

Sear, Sauce, and Serve

Mastering High-Heat, High-Flavor Cooking

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $11.99 $15.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 3, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Following this formula, Sear, Sauce, and Serve empowers readers to become a calm and thoroughly proficient cook, running the show in their own kitchens every night of the week. Rosenfeld teaches the principles of cooking over high heat with different types of foods — beef, chicken, fish, or vegetables — and provides more than 250 sauce recipes for while you sear and after you sear. Helpful illustrations guide you through the instructions.

High-heat cooking saves you time and the easy teaching methods encourage healthy home cooking. There is even a chapter on using affordable cuts of meat to fit any budget. By mastering the techniques you are free to be creative to come up with your own recipe to fit your mood.

Genre:

- On Sale

- May 3, 2011

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762442270

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use