Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

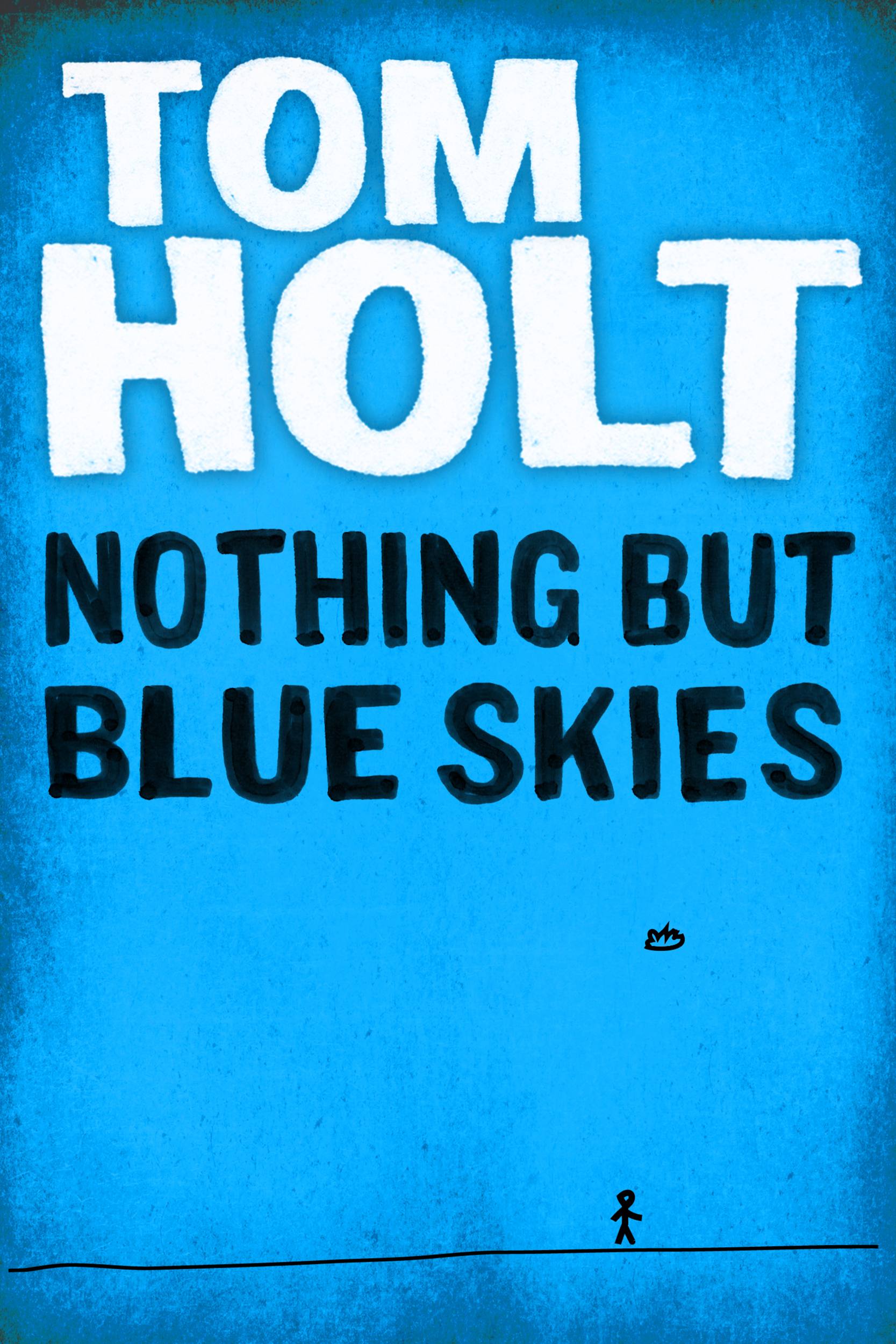

Nothing But Blue Skies

Contributors

By Tom Holt

Formats and Prices

Price

$3.99Format

Format:

ebook (Digital original) $3.99This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 4, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

There are many reasons why British summers are either non-existent or, alternatively, held on a Thursday. Many of these reasons are either scientific, mad, or both-but all of them are wrong, especially the scientific ones. The real reason why it rains perpetually from January 1st to December 31st is, of course, irritable Chinese Water Dragons. Karen is one such legendary creature. Ancient, noble, nearly indestructible and, for a number of wildly improbable reasons, working as a real estate agent, Karen is irritable quite a lot of the time. But now things have changed, and Karen’s no longer irritable. She’s furious.

- On Sale

- Sep 4, 2012

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Orbit

- ISBN-13

- 9780316233361

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use