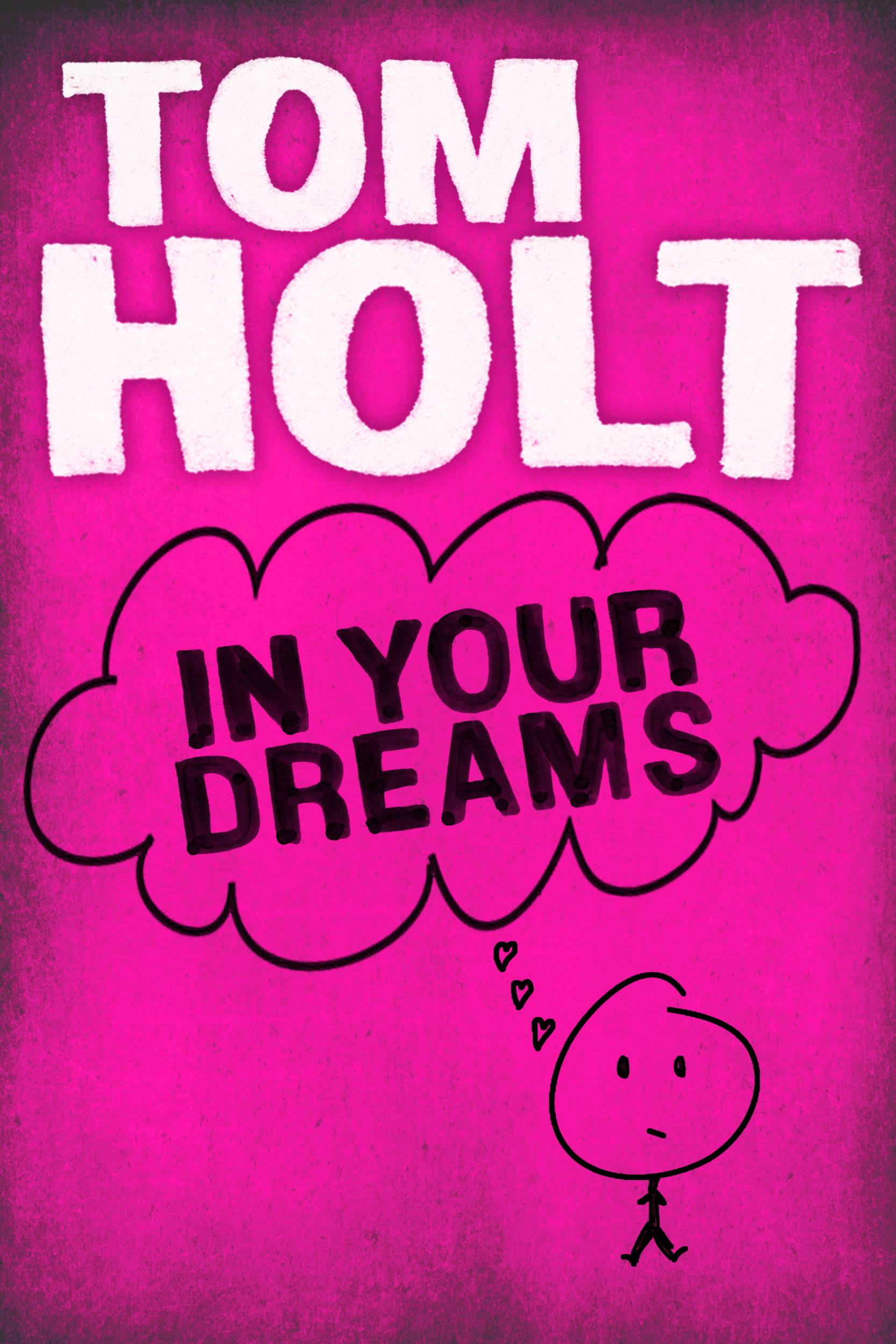

In Your Dreams

Contributors

By Tom Holt

Formats and Prices

Price

$5.99Format

Format:

ebook (Digital original) $5.99This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 4, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

“Tom Holt may be the most imaginative satirist to land on our shores since Douglas Adams.” — Christopher Moore, New York Times bestselling author

It's the kind of trick that deeply sinister companies like J.W. Wells & Co. pull all the time. Especially with employees who are too busy mooning over the office intern to think about what they're getting into. And it's why, right about now, Paul Carpenter is wishing he'd paid much less attention to the gorgeous Melze, and rather more to a little bit of job description small-print referring to "pest" control.

The J.W. Wells & Co. Series:

The Portable Door

In Your Dreams

Earth, Air, Fire and Custard

You Don't Have to Be Evil to Work Here, But It Helps

The Better Mousetrap

May Contain Traces of Magic

Other titles from Tom Holt:

Doughnut

When It's A Jar

The Outsorcerer's Apprentice

The Good, the Bad and the Smug

The Management Style of the Supreme Beings

An Orc on the Wild Side

Holt Writing as K. J. Parker:

Sixteen Ways to Defend a Walled City

How To Rule An Empire and Get Away With It

A Practical Guide to Conquering the World

- On Sale

- Sep 4, 2012

- Page Count

- 480 pages

- Publisher

- Orbit

- ISBN-13

- 9780316233170

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use