Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

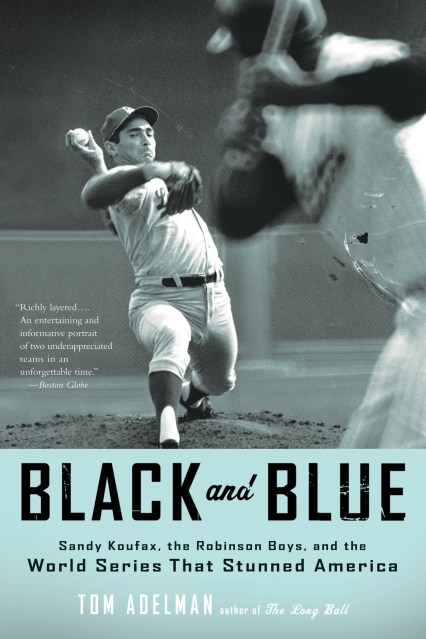

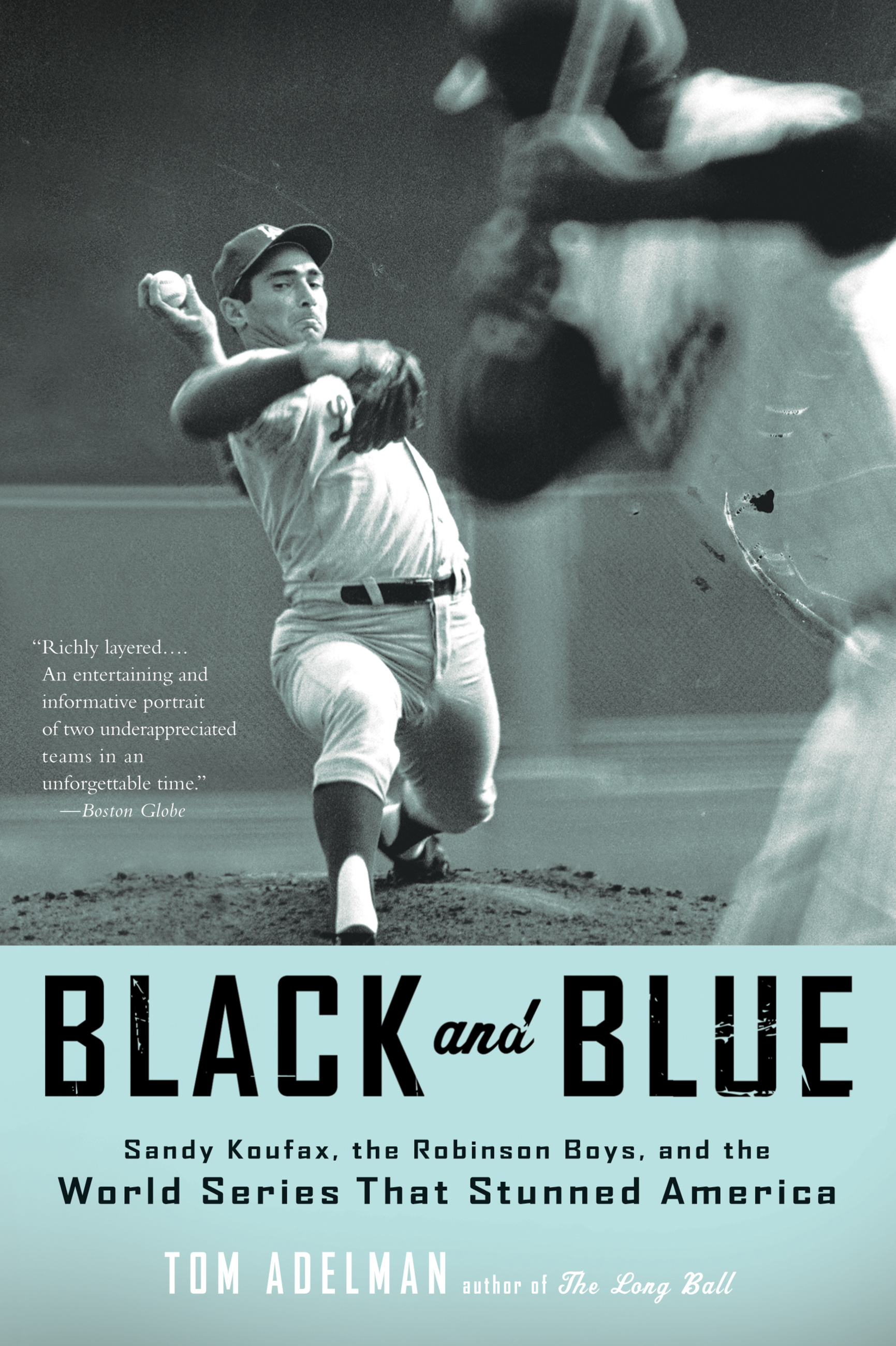

Black and Blue

Sandy Koufax, the Robinson Boys, and the World Series That Stunned America

Contributors

By Tom Adelman

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 30, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Baltimore 1966. Suffering through a summer of heated racial animosity, baseball fans look hungrily to the Orioles to bring new respect to their once-great city. Their young team of no-name kids and promising prospects appears to have been strengthened by the recent addition of veteran slugger Frank Robinson – but the former National League MVP is bad news (it is rumored), washed up and unreliable.

To lay these rumors to rest, Robby must play harder than he’s ever played before. In his first year in the league, against unfamiliar pitchers in new ballparks, he resoundingly proves his worth — to his city, his team, and himself — by delivering a Triple Crown performance. Aided by a hilarious and memorable cast of characters — the gentlemanly southerner Brooks Robinson and the wickedly inventive prankster Moe Drabowsky, a pitching staff of unknown kids like Jim Palmer and Dave McNally, and a gargantuan yet nimble fielder called Boog” — Frank Robinson delivers his new team to its first World Series. But before they take it all, the Orioles must unseat the reigning champion Los Angeles Dodgers.

With America’s cities in mounting turmoil, Los Angeles seems like another world altogether, a sunny land of surfers and movie stars. Comfortably dwelling in this higher plane is pitching ace Sandy Koufax, arguably the greatest lefthander in baseball history, behind whom the Dodgers have won two of the previous three World Series, replacing the Yankees as the sport’s dominant team. Though battling agonizing arthritis throughout the season, the godlike Koufax has nonetheless persevered to win twenty-seven games in 1966, a personal best. Few outside Baltimore give the Orioles more than a fighting chance against such series veterans as Koufax, Don Drysdale, Maury Wills, Tommy Davis, and the rest. Experts are betting that the Dodgers can sweep it in four.

“What transpires instead astonishes the nation, as the greatest pitching performance in World Series history is capped by a redemption beyond imagining.” — Book Jacket

Genre:

- On Sale

- May 30, 2010

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316075435

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use