Promotion

Sign up for our newsletters to receive 20% off! Shop now. Exclusions apply.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

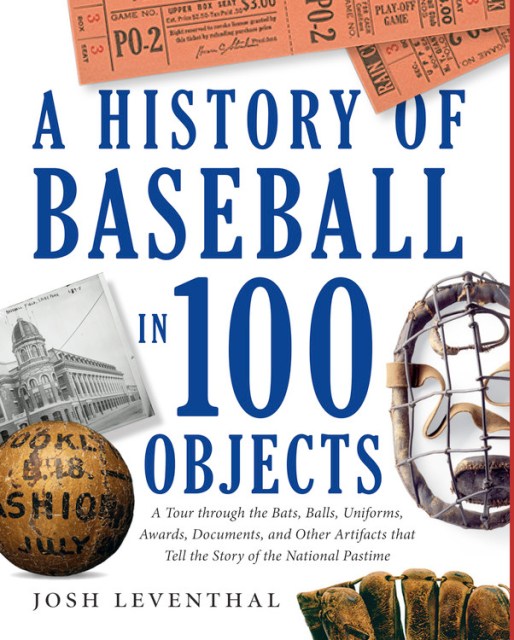

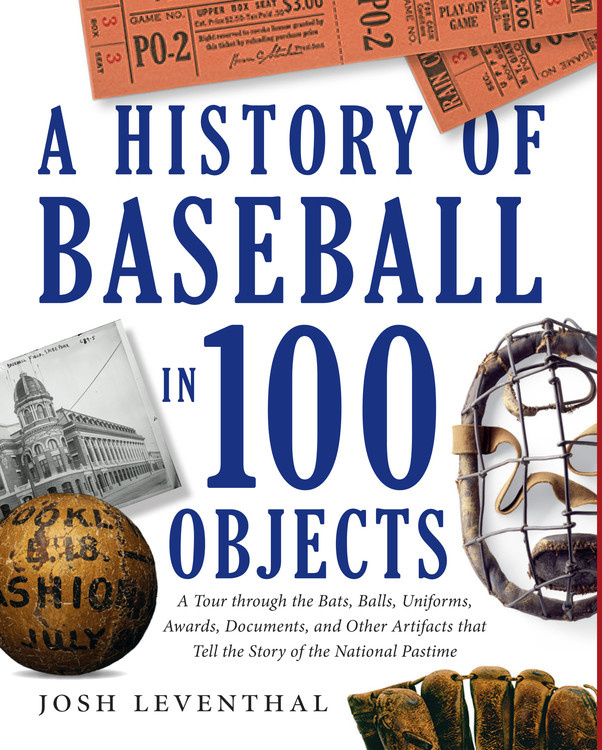

History of Baseball in 100 Objects

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$29.95Format

Format:

- Hardcover $29.95

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 5, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A History of Baseball in 100 Objects is a visual and historical record of the game as told through essential documents, letters, photographs, equipment, memorabilia, food and drink, merchandise and media items, and relics of popular culture, each of which represents the history and evolution of the game.

Among these objects are the original ordinance banning baseball in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, in 1791 (the earliest known reference to the game in America); the “By-laws and Rules of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club,” 1845 (the first codified rules of the game); Fred Thayer’s catcher’s mask from the 1870s (the first use of this equipment in the game); a scorecard from the 1903 World Series (the first World Series); Grantland Rice’s typewriter (the role of sportswriters in making baseball the national pastime); Babe Ruth’s bat, circa 1927 (the emergence of the long ball); Pittsburgh Crawford’s team bus, 1935 (the Negro Leagues); Jackie Robinson’s Montreal Royals uniform, 1946 (the breaking of the color barrier); a ticket stub from the 1951 Giants-Dodgers playoff game and Bobby Thomson’s “Shot Heard ‘Round The World” (one of baseball’s iconic moments); Sandy Koufax’s Cy Young Award, 1963 (the era of dominant pitchers); a “Reggie!” candy bar, 1978 (the modern player as media star); Rickey Henderson’s shoes, 1982 (baseball’s all-time-greatest base stealer); the original architect’s drawing for Oriole Park at Camden Yards (the ballpark renaissance of the 1990s); and Barry Bond’s record-breaking bat (the age of Performance Enhancing Drugs).

A full-page photograph of the object is accompanied by lively text that describes the historical significance of the object and its connection to baseball’s history, as well as additional stories and information about that particular period in the history of the game.

- On Sale

- May 5, 2015

- Page Count

- 496 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9781579129910

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use