Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

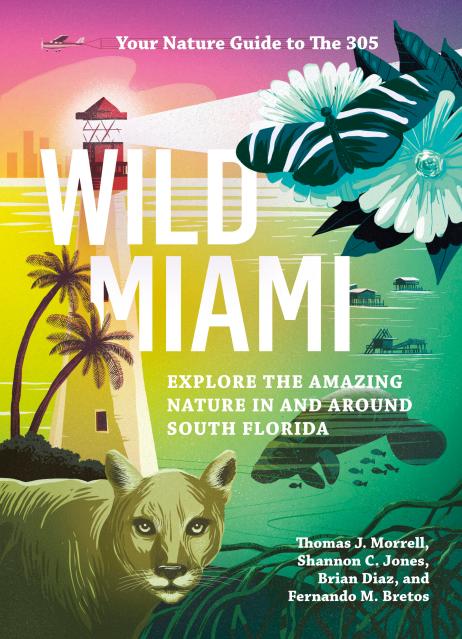

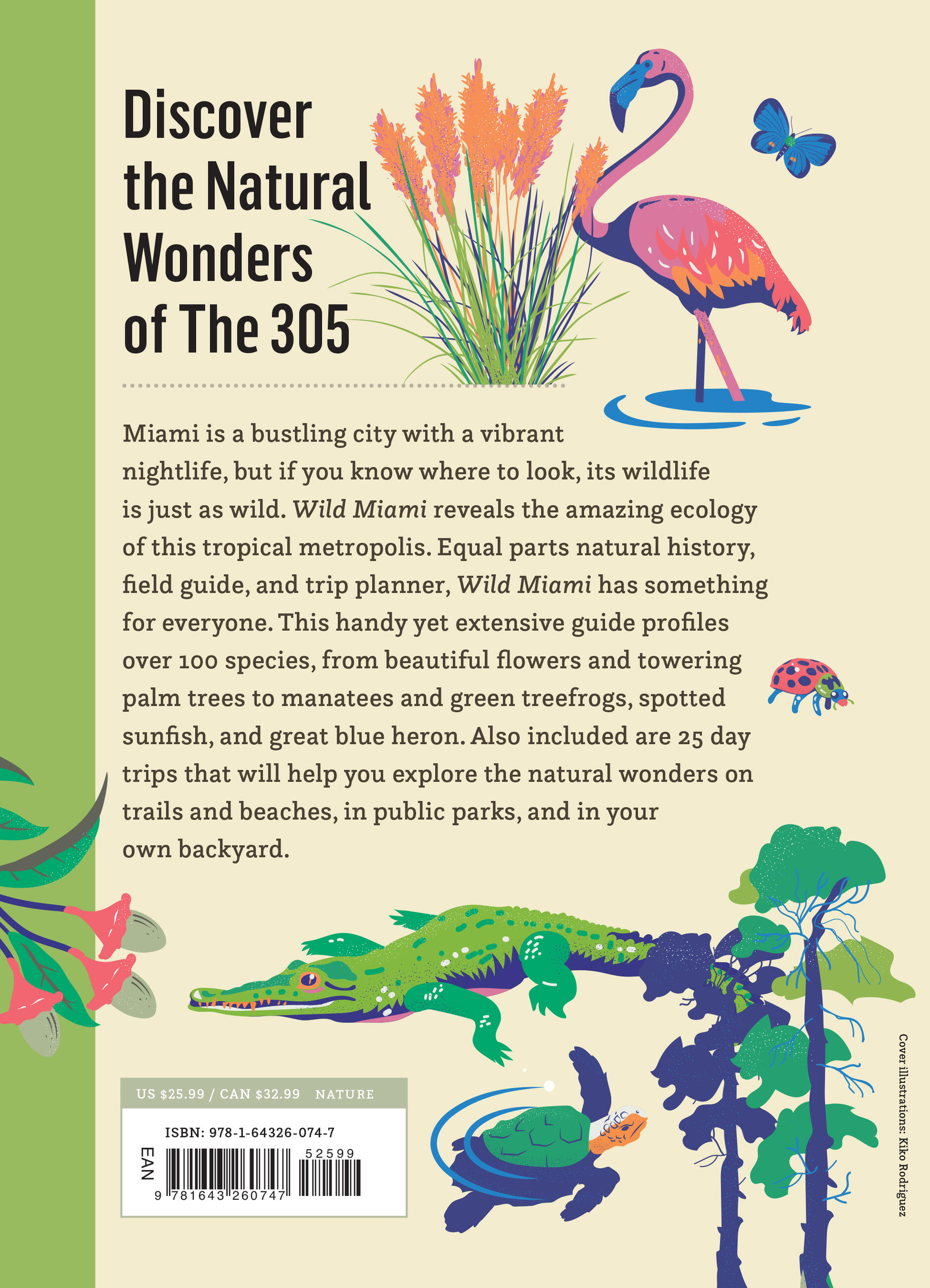

Wild Miami

Explore the Amazing Nature in and Around South Florida

Contributors

By TJ Morrell

By Brian Diaz

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 3, 2023

- Page Count

- 376 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781643260747

Price

$25.99Price

$32.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $25.99 $32.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 3, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Miami may be a bustling city with a vibrant nightlife, but its wildlife is just as wild, if you know where to look. Wild Miami reveals the amazing ecology of this tropical metropolis. Equal parts natural history, field guide, and trip planner, Wild Miami has something for everyone. This handy yet extensive guide looks at the factors that shape local nature and profiles over 100 local species, from beautiful flowers and towering palm trees to manatees and green treefrogs, spotted sunfish, and great blue heron. Also included are descriptions of day trips that help you explore natural wonders on hiking trails and beaches, in public parks, and in your own backyard.

Genre:

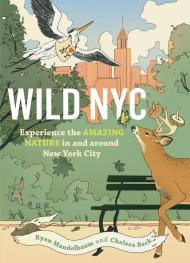

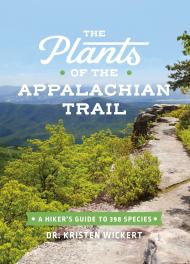

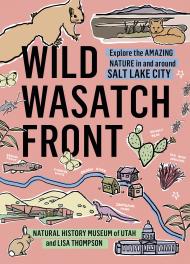

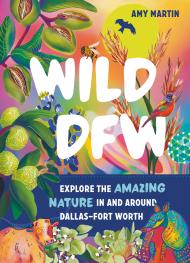

Series:

-

“The most notable and engaging features of this work are its incredible color photography and its vibrant layout. Authored by four passionate scientists and conservation professionals, the pictures and their descriptions bring these species and their habitats to life. These alone make the book mandatory. Readers, both leisurely browsers and students, and native Miamians, Floridians, and citizens all over the world will likely find it engaging and enriching.”Library Journal