Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

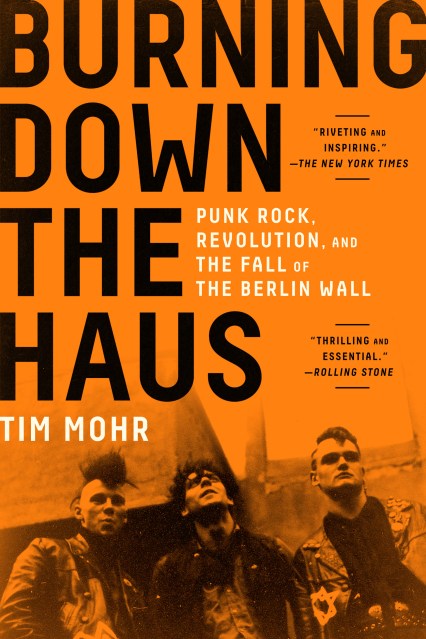

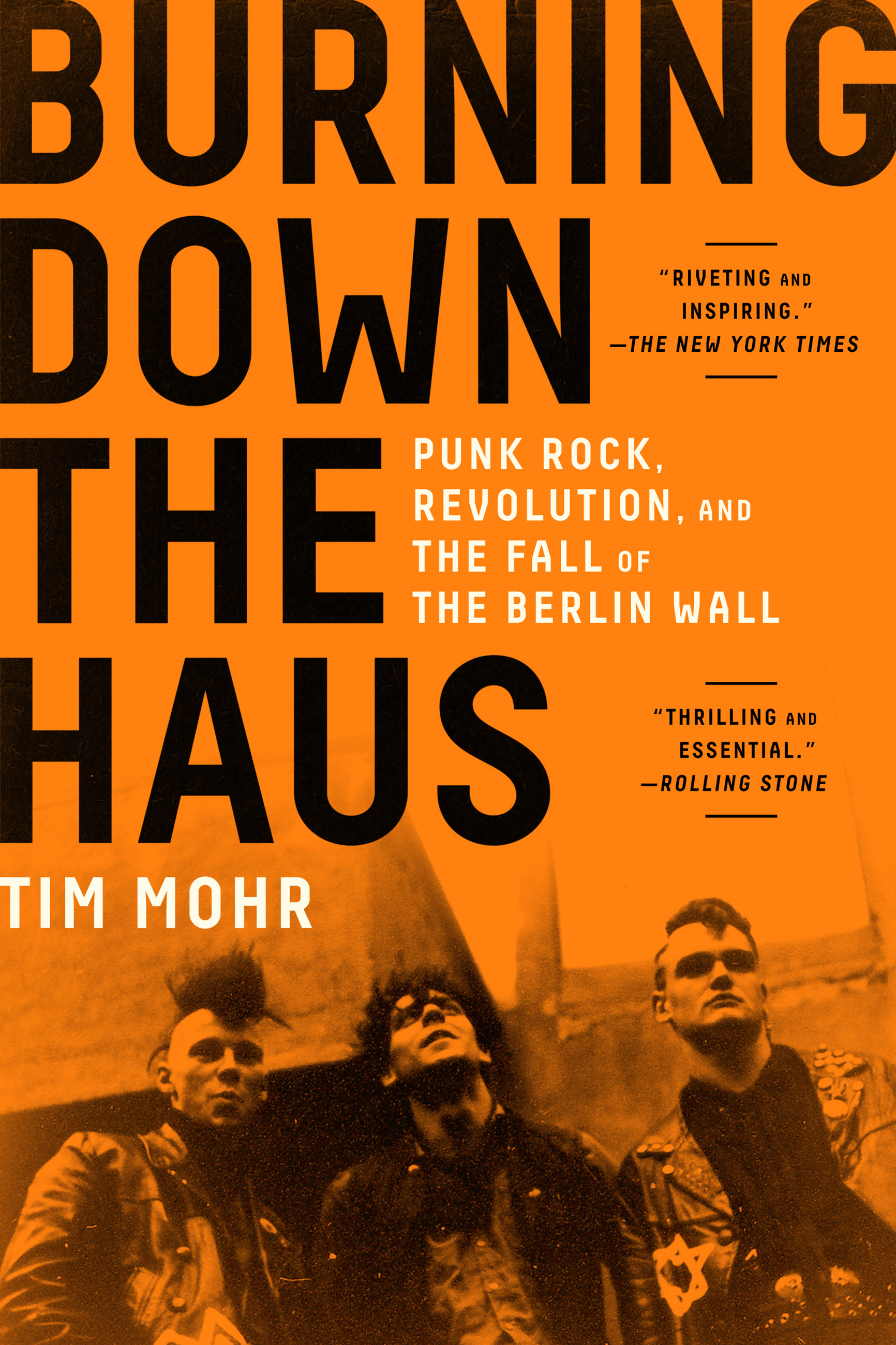

Burning Down the Haus

Punk Rock, Revolution, and the Fall of the Berlin Wall

Contributors

By Tim Mohr

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $16.95 $22.95 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 11, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

NAMED ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR BY Rolling Stone * BookPage * Amazon * Rough Trade

Longlisted for the Carnegie Medal for Excellence

“[A] riveting and inspiring history of punk’s hard-fought struggle in East Germany.” —The New York Times Book Review

“A thrilling and essential social history that details the rebellious youth movement that helped change the world.” —Rolling Stone

“Original and inspiring . . . Mr. Mohr has written an important work of Cold War cultural history.” —The Wall Street Journal

“Wildly entertaining . . . A thrilling tale . . . A joy in the way it brings back punk’s fury and high stakes.”—Vogue

It began with a handful of East Berlin teens who heard the Sex Pistols on a British military radio broadcast to troops in West Berlin, and it ended with the collapse of the East German dictatorship. Punk rock was a life-changing discovery. The buzz-saw guitars, the messed-up clothing and hair, the rejection of society and the DIY approach to building a new one: in their gray surroundings, where everyone’s future was preordained by some communist apparatchik, punk represented a revolutionary philosophy—quite literally, as it turned out.

But as these young kids tried to form bands and became more visible, security forces—including the dreaded secret police, the Stasi—targeted them. They were spied on by friends and even members of their own families; they were expelled from schools and fired from jobs; they were beaten by police and imprisoned. Instead of conforming, the punks fought back, playing an indispensable role in the underground movements that helped bring down the Berlin Wall.

This secret history of East German punk rock is not just about the music; it is a story of extraordinary bravery in the face of one of the most oppressive regimes in history. Rollicking, cinematic, deeply researched, highly readable, and thrillingly topical, Burning Down the Haus brings to life the young men and women who successfully fought authoritarianism three chords at a time—and is a fiery testament to the irrepressible spirit of revolution.

Longlisted for the Carnegie Medal for Excellence

“[A] riveting and inspiring history of punk’s hard-fought struggle in East Germany.” —The New York Times Book Review

“A thrilling and essential social history that details the rebellious youth movement that helped change the world.” —Rolling Stone

“Original and inspiring . . . Mr. Mohr has written an important work of Cold War cultural history.” —The Wall Street Journal

“Wildly entertaining . . . A thrilling tale . . . A joy in the way it brings back punk’s fury and high stakes.”—Vogue

It began with a handful of East Berlin teens who heard the Sex Pistols on a British military radio broadcast to troops in West Berlin, and it ended with the collapse of the East German dictatorship. Punk rock was a life-changing discovery. The buzz-saw guitars, the messed-up clothing and hair, the rejection of society and the DIY approach to building a new one: in their gray surroundings, where everyone’s future was preordained by some communist apparatchik, punk represented a revolutionary philosophy—quite literally, as it turned out.

But as these young kids tried to form bands and became more visible, security forces—including the dreaded secret police, the Stasi—targeted them. They were spied on by friends and even members of their own families; they were expelled from schools and fired from jobs; they were beaten by police and imprisoned. Instead of conforming, the punks fought back, playing an indispensable role in the underground movements that helped bring down the Berlin Wall.

This secret history of East German punk rock is not just about the music; it is a story of extraordinary bravery in the face of one of the most oppressive regimes in history. Rollicking, cinematic, deeply researched, highly readable, and thrillingly topical, Burning Down the Haus brings to life the young men and women who successfully fought authoritarianism three chords at a time—and is a fiery testament to the irrepressible spirit of revolution.

Genre:

-

“[A] riveting and inspiring history of punk’s hard-fought struggle in East Germany. The book chronicles, with cinematic detail, the commitment and defiance required of East German punks as they were forced to navigate constant police harassment and repression.”

—The New York Times Book Review

“A thrilling and essential social history that details the rebellious youth movement that helped change the world.”

—Rolling Stone

“Burning Down the Haus deftly chronicles the formation of East Germany’s punk scene within a fragmented country under constant monitoring by a secret police agency, the Stasi. This is a work that encapsulates a particular musical world but, more crucially, shows how the society around it shaped the scene in idiosyncratic ways.”

—Pitchfork

“Wildly entertaining . . . A thrilling tale . . . A joy in the way it brings back punk’s fury and high stakes.”

—Vogue

“Gripping.”

—Billboard

“The new book Burning Down the Haus fastidiously traces the self-discovery of punks in the socialist dictatorship of East Germany, and the violence and repression they endured on the way to freedom.”

—NPR

“Burning Down the Haus is a gripping, powerful story of self-expression in the face of adversity . . . We can see echoes of the time it describes in groups like Pussy Riot, who risk imprisonment and possible assassination in President Vladimir Putin’s Russia. The story of East German punk is one of rock and roll’s greatest unheard tales of courage. Or it was until Tim Mohr came along.”

—The Houston Chronicle

“Remarkable . . . revelatory . . . amazing.”

—Longreads

“Original and inspiring . . . Mr. Mohr has written an important work of Cold War cultural history.”

—The Wall Street Journal

“Mohr takes readers on a fascinating trip through the 1980s, focusing on East German teenagers that embraced the punk lifestyle and ultimately would play a role in the fall of the Berlin Wall. Mohr is a great storyteller and manages to make history read like you are there directly witnessing it.”

—The Hype Magazine

“What makes this book such a fascinating read is that Mohr has recreated the period almost as an oral history . . . it also brings the era and the reality of the times to life beautifully. Burning Down the Haus not only dispels the myth that the West and capitalism were responsible for bringing down the Berlin Wall, it also provides the example of how the oppressed can effect change from the bottom up – something as pertinent today as it was in East Germany in the 80s. This is a beautifully written and important book about the power of ordinary people to make a difference and how punk is more than just a type of music.”

—Blogcritics.com

“Mohr pens an inspiring history of a punk scene that literally tore down a symbol of division and oppression.”

—Library Journal

“Lively . . . Compelling . . . A front-row seat to the events of the ’80s. This take on punk evolution is engaging, enlightening, and well worth checking out.”

—Publishers Weekly, starred review

“Translator, editor, and former Berlin DJ Mohr energetically details the origins of East German punks . . . Mohr tells a frantic and exciting true story of music versus dictatorship, and the infamous wall it helped bring down.”

—Booklist, starred review

“An appealing, lively cultural history worth reading in an era of corporate punk nostalgia.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Incendiary . . . Compulsively readable and beautifully researched, Burning Down the Hausrecords the critical role that punks played in the German resistance movements of the 1980s, up to and beyond the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 . . . inspiring.”

—BookPage

“Mohr takes readers on a fascinating trip through the 1980s, focusing on East German teenagers that embraced the punk lifestyle and ultimately would play a role in the fall of the Berlin Wall. Mohr is a great storyteller and manages to make history read like you are there directly witnessing it.”

—The Hype Magazine

“Burning Down the Haus stands as a testament to the DIY ethos as a response to oppression, which, in this day and age, may be exactly what American society needs.”

—Harvard Crimson

“Burning Down the Haus is not just an immersion into the punk rock scene of East Berlin, it’s the story of the cultural and political battles that have shaped the world we live in today. Tim Mohr delivers the soundtrack for the revolution that we’ve all been waiting for.”

—DW Gibson, author of The Edge Becomes the Center: An Oral History of Gentrification in the Twenty-First Century

“In East Germany, where non-conformity meant jail time, punks’ ripped clothes and spiked hair were a show of courage and defiance. Squatting in derelict apartments and burning their lyrics before the secret police could get ahold of them, these teenagers wrote the soundtrack for a rebellion that helped bring down the Berlin Wall. Tim Mohr tells the story of their DIY revolution with the thoroughness of a historian and the panache of a cultural insider. Burning Down the Haus is a riveting cultural history that also serves as a rallying call against authoritarianism everywhere.”

—Ruth Franklin, author of the NBCC Award-winning Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life

“Equal parts terrifying and exhilarating, Burning Down the Haus is a fabulously alive history of punk rock behind the Iron Curtain, where simply dressing like a punk could get you hauled in by Stasi, the dreaded East German secret police. Mohr ties the fearless music-driven resistance to authoritarianism and mass surveillance in the 1980s to our current fraught times, showing how even the most formidable forms of oppression can be shaken by highly motivated, creative kids with riotous rage and a driving beat. A thrilling, inspiring read.”

—Rob Spillman, editor of Tin House and author of All Tomorrow’s Parties

“You say you want a revolution? Tim Mohr’s spellbinding Burning Down the Haus reveals how a bunch of young East German punks in the 1980s made their wild music into a clarion loud enough to topple the Berlin Wall. With a sharp eye for the prosaic brutality of the repressive state and an ear locked on the furies in the music, Mohr has crafted an unforgettable story that is part cultural history, part political thriller and entirely true.”

—Peter Ames Carlin, author of Homeward Bound: The Life of Paul Simon

“Berlin has always been a crazy city, and a dramatic stage for the epic struggle between powerful ideological forces and the individual desire to be free. In case you weren’t sure just how political music, fashion, and a certain attitude can be: read this book. Burning Down the Haus is wonderful.”

—Norman Ohler, author of Blitzed

“This is a crazily inspiring, strange, beautiful story that deserves to be remembered, and Mohr is a wonderfully compassionate writer. What a combination!”

—Johann Hari, New York Times bestselling author of Chasing the Scream and Lost Connections

“The best punk book since Please Kill Me.”

—Legs McNeil, author of Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk

“Tim Mohr’s book details a fascinating period of time in the history of punk music. I am so glad he documented that moment in history for punk rock and for the world.”

—Greg Graffin, singer/songwriter for Bad Religion and author of Population Wars and Anarchy Evolution

“The true story of how teenage kicks turned into political opposition. With meticulous research and impassioned prose, Tim Mohr brings to life the saga of a bunch of East German punk rock kids who broke the state that wanted to break them. A book to warm an old punk’s heart.”

—Claire Dederer, author of Love and Trouble

PRAISE FOR THE GERMAN EDITION OF BURNING DOWN THE HAUS

“A wonderful book.”

—Berliner Zeitung

“A historical drama that takes your breath away.”

—Neustadt-Gefluester (Dresden)

“Mohr digs into the subject of East German punk like nobody before.”

—Rolling Stone Germany

“Cinematic...Makes the reader feel a witness to the events . . . A lively, enthralling adventure story; the tone combines a dramatic Hollywood epic with a meticulous documentary.”

—Falter (Vienna)

“You get taken in quickly, and just as quickly you have a lively image of the situation . . . The storytelling style is like having a movie in your head.”

—Lutz Schramm (German radio personality)

“A wonderful, atmospheric look at a hidden world.”

—Classic Rock

- On Sale

- Sep 11, 2018

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Algonquin Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781616208844

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use