Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

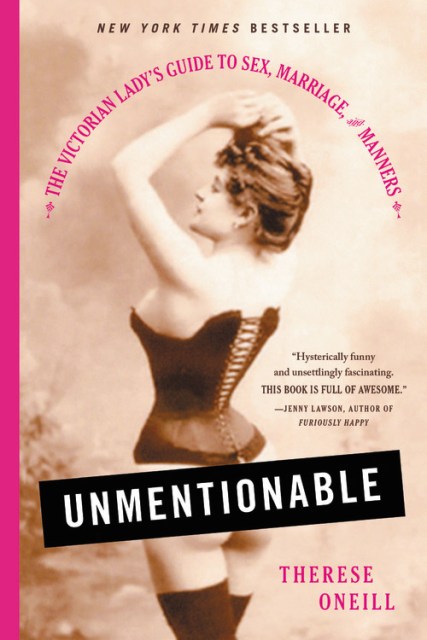

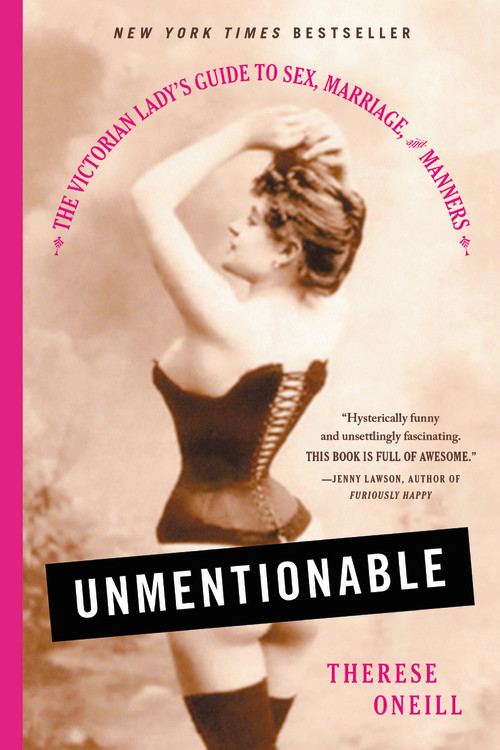

Unmentionable

The Victorian Lady's Guide to Sex, Marriage, and Manners

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 8, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Have you ever wished you could live in an earlier, more romantic era? Ladies, welcome to the 19th century, where there’s arsenic in your face cream, a pot of cold pee sits under your bed, and all of your underwear is crotchless. (Why? Shush, dear. A lady doesn’t question.)

Unmentionable is your hilarious, illustrated, scandalously honest (yet never crass) guide to the secrets of Victorian womanhood, giving you detailed advice on: What to wear Where to relieve yourself How to conceal your loathsome addiction to menstruating What to expect on your wedding night How to be the perfect Victorian wife Why masturbating will kill you And more!

Irresistibly charming, laugh-out-loud funny, and featuring nearly 200 images from Victorian publications, Unmentionable will inspire a whole new level of respect for Elizabeth Bennett, Scarlet O’Hara, Jane Eyre, and all of our great, great grandmothers. (And it just might leave you feeling ecstatically grateful to live in an age of pants, super absorbency tampons, epidurals, anti-depressants, and not dying of the syphilis your husband brought home.)

Unmentionable is your hilarious, illustrated, scandalously honest (yet never crass) guide to the secrets of Victorian womanhood, giving you detailed advice on: What to wear Where to relieve yourself How to conceal your loathsome addiction to menstruating What to expect on your wedding night How to be the perfect Victorian wife Why masturbating will kill you And more!

Irresistibly charming, laugh-out-loud funny, and featuring nearly 200 images from Victorian publications, Unmentionable will inspire a whole new level of respect for Elizabeth Bennett, Scarlet O’Hara, Jane Eyre, and all of our great, great grandmothers. (And it just might leave you feeling ecstatically grateful to live in an age of pants, super absorbency tampons, epidurals, anti-depressants, and not dying of the syphilis your husband brought home.)

Genre:

- On Sale

- May 8, 2018

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Back Bay Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316357906

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use