By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

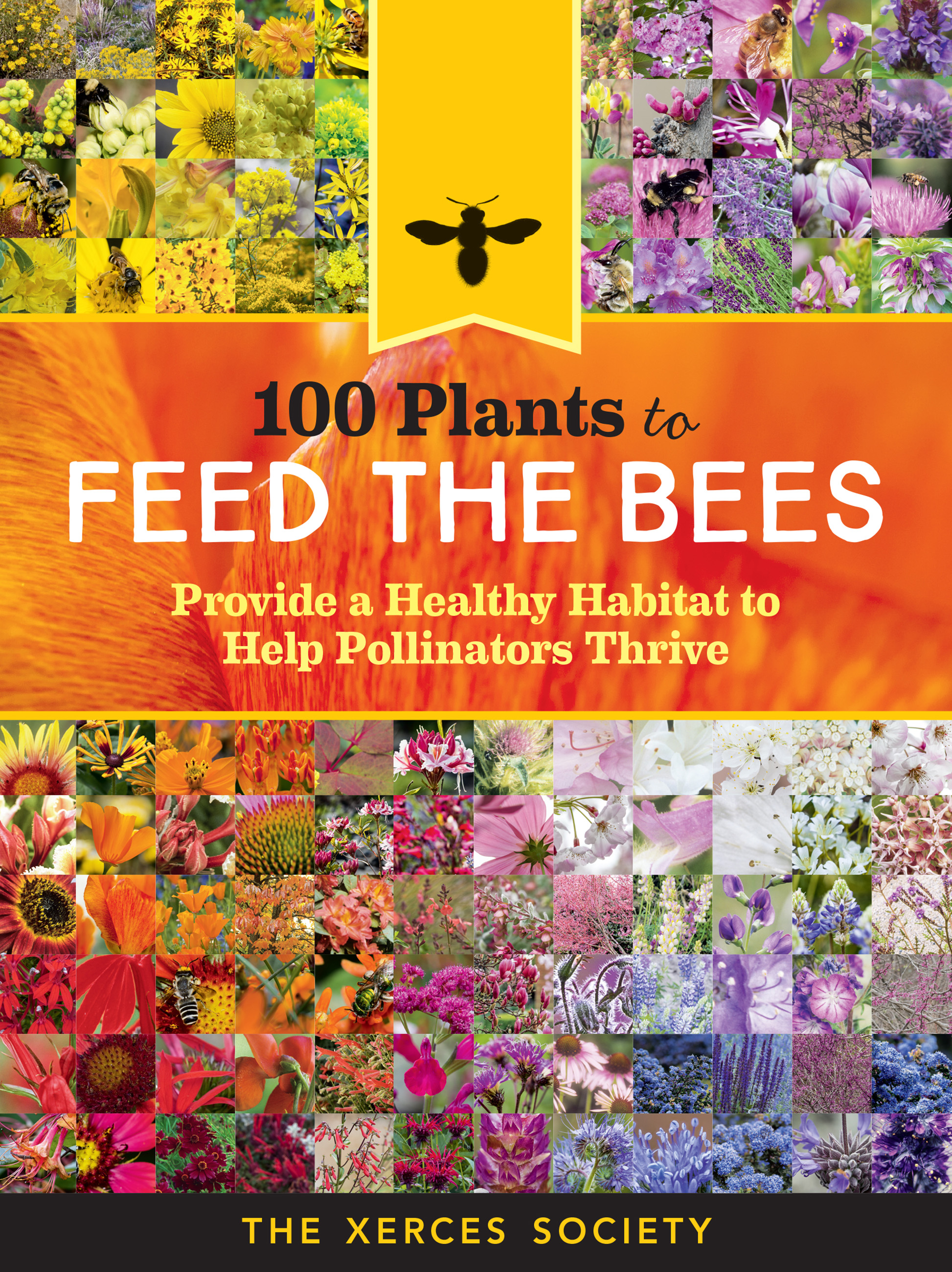

100 Plants to Feed the Bees

Provide a Healthy Habitat to Help Pollinators Thrive

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 29, 2016

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Storey

- ISBN-13

- 9781612127026

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $26.95 $33.95 CAD

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 29, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The international bee crisis is threatening our global food supply, but this user-friendly field guide shows what you can do to help protect our pollinators. The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation offers browsable profiles of 100 common flowers, herbs, shrubs, and trees that support bees, butterflies, moths, and hummingbirds. The recommendations are simple: pick the right plants for pollinators, protect them from pesticides, and provide abundant blooms throughout the growing season by mixing perennials with herbs and annuals! 100 Plants to Feed the Bees will empower homeowners, landscapers, apartment dwellers — anyone with a scrap of yard or a window box — to protect our pollinators.

-

2017 GWA Media Awards Silver Medal winner

“A wonderful and much-needed book that will inspire and inform the creation of bee-friendly wildflower gardens. Perhaps we can turn our gardens, neighborhoods, towns, and cities into vast, colorful havens for bees, butterflies, and other vital insects!”

— Dave Goulson, biologist, founder of the Bumblebee Conservation Trust, and author of A Sting in the Tale

“If you’re ready to help save the bees, this is a great place to start. No matter where you live, this well-organized companion shows you the best plants to use.”

— Joe Lamp’l, creator, executive producer, and host of Growing a Greener World®

“The ever-helpful Xerces Society shows us how to bring back our threatened species, one gorgeous garden at a time. Everybody wins!”

— Dar Williams, singer, songwriter, and environmental activist

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use