Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

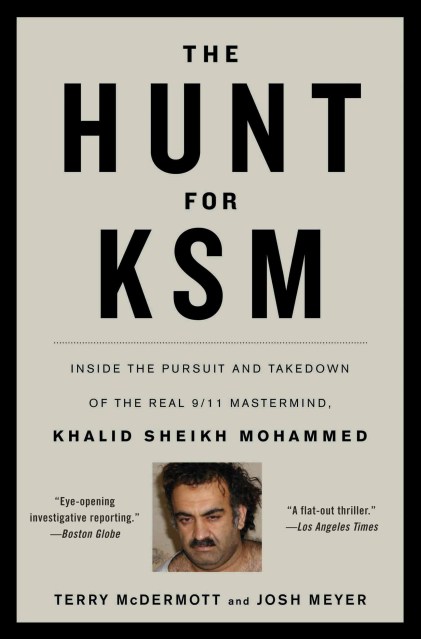

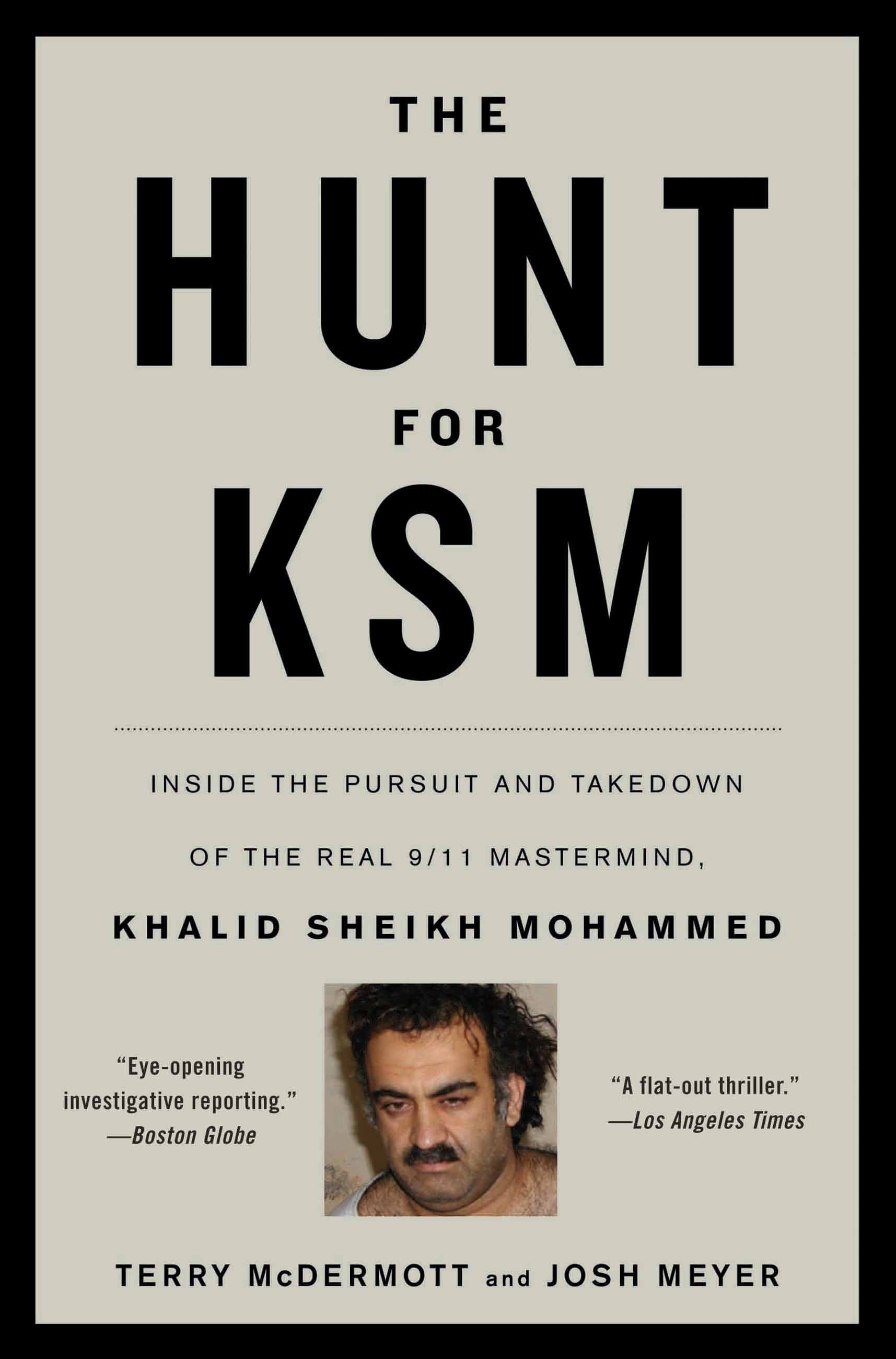

The Hunt for KSM

Inside the Pursuit and Takedown of the Real 9/11 Mastermind, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed

Contributors

By Josh Meyer

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$14.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $14.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 26, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Only minutes after United 175 plowed into the World Trade Center’s South Tower, people in positions of power correctly suspected who was behind the assault: Osama bin Laden and Al Qaeda. But it would be 18 months after September 11 before investigators would capture the actual mastermind of the attacks, the man behind bin Laden himself.

That monster is the man who got his hands dirty while Osama fled; the man who was responsible for setting up Al Qaeda’s global networks, who personally identified and trained its terrorists, and who personally flew bomb parts on commercial airlines to test their invisibility. That man withstood waterboarding and years of other intense interrogations, not only denying Osama’s whereabouts but making a literal game of the proceedings, after leading his pursuers across the globe and back. That man is Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, and he is still, to this day, the most significant Al Qaeda terrorist in captivity.

In The Hunt for KSM, Terry McDermott and Josh Meyer go deep inside the US government’s dogged but flawed pursuit of this elusive and dangerous man. One pair of agents chased him through countless false leads and narrow escapes for five years before 9/11. And now, drawing on a decade of investigative reporting and unprecedented access to hundreds of key sources, many of whom have never spoken publicly — as well as jihadis and members of KSM’s family and support network — this is a heart-pounding trip inside the dangerous, classified world of counterterrorism and espionage.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 26, 2012

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316202732

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use