Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

Madam Speaker

Nancy Pelosi and the Lessons of Power

Contributors

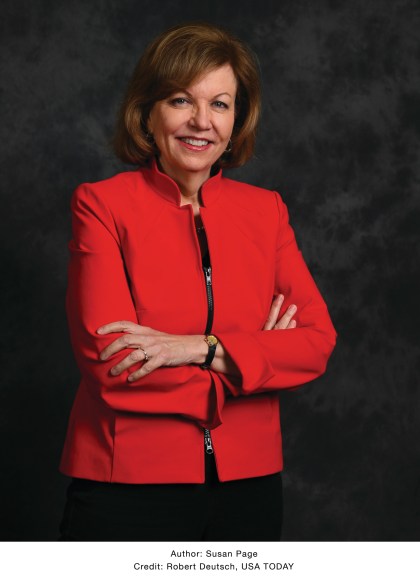

By Susan Page

Formats and Prices

Price

$32.50Price

$40.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $32.50 $40.00 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 20, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The definitive biography of Nancy Pelosi, the most powerful woman in American political history, written by New York Times bestselling author and USA Today Washington bureau chief Susan Page.

Featuring more than 150 exclusive interviews with those who know her best—and a series of in-depth, news-making interviews with Pelosi herself—MADAM SPEAKER is unprecedented in the scope of its exploration of Nancy Pelosi’s remarkable life and of her indelible impact on American politics.

Before she was Nancy Pelosi, she was Nancy D’Alesandro. Her father was a big-city mayor and her mother his political organizer; when she encouraged her young daughter to become a nun, Nancy told her mother that being a priest sounded more appealing. She didn’t begin running for office until she was forty-six years old, her five children mostly out of the nest. With that, she found her calling.

Nancy Pelosi has lived on the cutting edge of the revolution in both women’s roles and in the nation’s movement to a fiercer and more polarized politics. She has established herself as a crucial friend or formidable foe to U.S. presidents, a master legislator, and an indefatigable political warrior. She took on the Democratic establishment to become the first female Speaker of the House, then battled rivals on the left and right to consolidate her power. She has soared in the sharp-edged inside game of politics, though she has struggled in the outside game—demonized by conservatives, second-guessed by progressives, and routinely underestimated by nearly everyone.

All of this was preparation for the most historic challenge she would ever face, at a time she had been privately planning her retirement. When Donald Trump was elected to the White House, Nancy Pelosi became the Democratic counterpart best able to stand up to the disruptive president and to get under his skin. The battle between Trump and Pelosi, chronicled in this book with behind-the-scenes details and revelations, stands to be the titanic political struggle of our time.

-

“Long considered one of America’s finest journalists, Susan Page’s newest book cements her reputation as one of our foremost political biographers. In exploring the remarkable life of Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Susan has painted a compelling portrait of determination, resilience, and patriotism that is the essence of American democracy.”Former Secretary of State Madeleine K. Albright

-

"Impressive in scope, elegant in style, and extremely judicious in its use of evidence, Susan Page's MADAM SPEAKER is a must-read biographical portrait of the indomitable Nancy Pelosi. Page, one of America's most admired journalists, has a gift for delivering fresh behind-the-scenes anecdotes and recapturing watershed historical moments in colorful prose. Every page sparkles with revelations. Pelosi is the true power broker of our time. Highly recommended!"Douglas Brinkley, bestselling author of AMERICAN MOONSHOT: John F. Kennedy and the Great Space Race

-

"In this story of power, resolve and intrigue, Susan Page has a subject equal to her inordinate talents. She takes us behind the scenes with the Speaker of the House—the most powerful woman in American history—and shows us how Nancy Pelosi conquered a world of guys."John A. Farrell, New York Times bestselling author of RICHARD NIXON: THE LIFE

-

“Nancy Pelosi is a tough, ruthless, and energetic practitioner of the acquisition and use of political power. Anyone seeking to understand the House of Representatives and the House Democratic Party has to start with Speaker Pelosi. Susan Page has written that lesson plan for all to read.”Newt Gingrich

-

"With her biography of First Lady Barbara Bush and her new book about Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Susan Page has distinguished herself as a chronicler of women public figures who defied odds, raised eyebrows, and ultimately found that being true to themselves and not worrying about what others thought or said about them was the key to success and happiness as they defined it. As with her first biography, MADAM SPEAKER will be a resource to historians and anyone who wants to understand the influence this powerful, sometimes controversial, occasionally ruthless, and fiercely determined woman has had on our national life."Dana Perino, New York Times bestselling author of AND THE GOOD NEWS IS...

-

"Scoopy and insightful."The New York Times

-

“[MADAM SPEAKER provides] a much deeper understanding of, and appreciation for, the work it takes for a woman to harness, maintain and wield authority that was once reserved exclusively for men."Washington Post

-

"Even longtime watchers of House Speaker Nancy Nancy Pelosi will learn something new about the most powerful woman in the country—and how she got that way—from...MADAM SPEAKER."Los Angeles Times

-

"Page delivers a worthwhile and documented read...MADAM SPEAKER makes clear that the speakership was not a job Pelosi spent a lifetime craving but it is definitely a role she wanted and, more importantly, mastered."The Guardian

-

"MADAM SPEAKER traces Pelosi’s life and work in a readable, engaging biography that takes us from Pelosi’s Baltimore upbringing through her current term as speaker in the Biden administration. [A] valuable overview of a singular American politician. The definitive biography of the House Speaker."USA Today

-

“Insightful book on a consequential woman in Washington. It’s a terrific read.”Peter Baker, The New York Times

-

“I can’t imagine what a pleasure it must have been to be working on this.”Mika Brzezinski, MSNBC

-

“Great biography...[Page’s] new book is excellent.”Jake Tapper, CNN

-

“...great book.”Andrea Mitchell, MSNBC

-

“... very interesting, definitive biography... go out and buy it.”Jonathan Karl, ABC News

-

“A fascinating read...I think we all thought we knew a lot about Nancy Pelosi, but [Page] managed to find out a lot more."Judy Woodruff, PBS NewsHour

-

“A balanced, informative biography."Kirkuss

- On Sale

- Apr 20, 2021

- Page Count

- 448 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781538750698

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use