Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

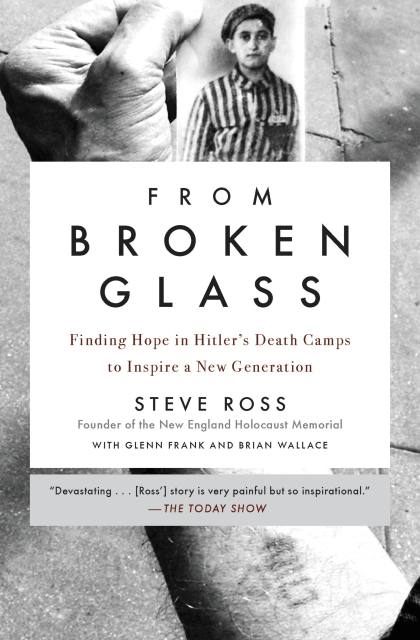

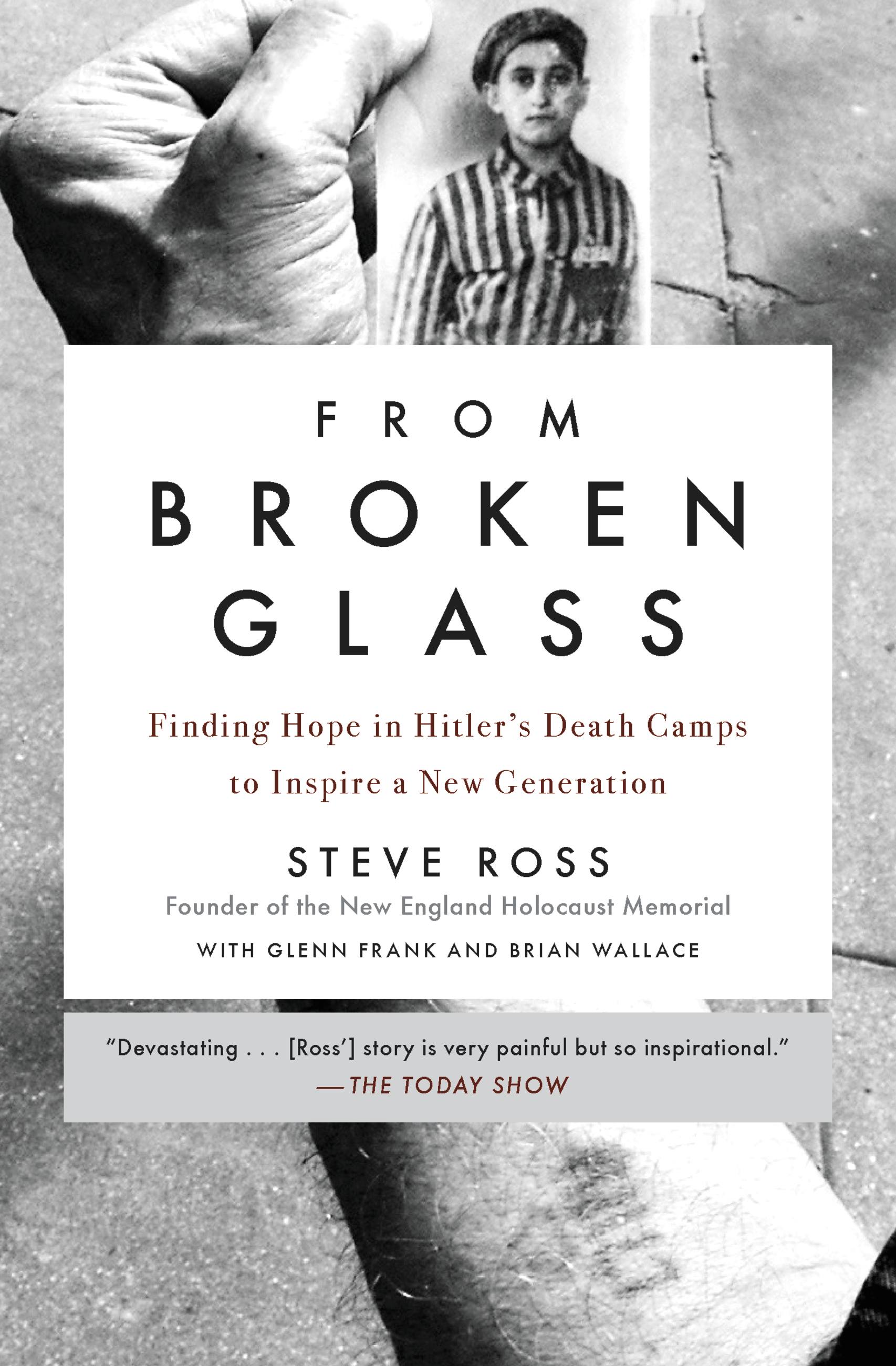

From Broken Glass

My Story of Finding Hope in Hitler's Death Camps to Inspire a New Generation

Contributors

By Steve Ross

With Glenn Frank

With Brian Wallace

Foreword by Ray Flynn

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$14.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $14.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.49 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 15, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

On August 14, 2017, two days after a white-supremacist activist rammed his car into a group of anti-Fascist protestors, killing one and injuring nineteen, the New England Holocaust Memorial was vandalized for the second time in as many months. At the base of one of its fifty-four-foot glass towers lay a pile of shards. For Steve Ross, the image called to mind Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass in which German authorities ransacked Jewish-owned buildings with sledgehammers.

Ross was eight years old when the Nazis invaded his Polish village, forcing his family to flee. He spent his next six years in a day-to-day struggle to survive the notorious camps in which he was imprisoned, Auschwitz-Birkenau and Dachau among them. When he was finally liberated, he no longer knew how old he was, he was literally starving to death, and everyone in his family except for his brother had been killed.

Ross learned in his darkest experiences–by observing and enduring inconceivable cruelty as well as by receiving compassion from caring fellow prisoners–the human capacity to rise above even the bleakest circumstances. He decided to devote himself to underprivileged youth, aiming to ensure that despite the obstacles in their lives they would never experience suffering like he had. Over the course of a nearly forty-year career as a psychologist working in the Boston city schools, that was exactly what he did. At the end of his career, he spearheaded the creation of the New England Holocaust Memorial, a site millions of people including young students visit every year.

Equal parts heartrending, brutal, and inspiring, From Broken Glass is the story of how one man survived the unimaginable and helped lead a new generation to forge a more compassionate world.

Genre:

-

"Devastating...For decades Ross worked with truants and dropouts in some of Boston's toughest neighborhoods. He had the uncanny ability to get struggling kids back in school and onto good jobs and even into college. His pitch: If he could survive what he did, you could survive anything...[Ross'] story is very painful but so inspirational."The Today Show

-

"From Broken Glass is a captivating and deeply personal story of a young boy's experience in the Holocaust, and the ways that event shaped his life as an adult in America. Ross's remarkably detailed account stands as a testament to the resilience of the human spirit. It is relevant to this day, a reminder of what can happen when we lose sight of the humanity of others in society."Senator Dianne Feinstein

-

"While Ross's is a work of history, it feels timely....Donald Trump's presidency has coincided with a marked uptick in anti-Semitic crimes, including the smashing of two glass panels at the memorial in Boston last year....One of the most striking things about the book is how [Ross] manages to maintain hope."The Boston Globe

-

"Striking, fierce, and ultimately uplifting, From Broken Glass is the moving story of how one man found his moral purpose in the crucible of the Holocaust and waged a life-long war against prejudice in all its forms. Just when we need it most, Steve Ross offers our nation a rallying cry for how we can overcome the hatred that divides us."Robert Trestan, New England Regional Director, Anti-DefamationLeague

-

"Remarkable...a profound and compelling addition to the literature of the Holocaust at a time when it is more critical than ever to understand both the horrifying depths to which its perpetrators sank and the astonishing capacity for generosity and compassion of the heartbreakingly few survivors. No matter how many memoirs of that terrible time you have read, you will find something new in these pages. There are scenes--a Ukrainian child's shiny black boots spattered with blood, a father eating his beloved small son's mouthful of bread--that will haunt me forever. And there are moments also of inspiring tenacity, nearly incomprehensible open-heartedness that I hope never to forget."Ayelet Waldman, bestselling author of Love and Treasure

-

"[Ross] heal[ed] others to heal himself from the horrors of the Holocaust...But the theme that comes through most in From Broken Glass is how utterly impossible it is for those who suffered this greatest of human traumas to ever forget, to fix that which broke them more than seventy years ago."The Washington Post

-

"From Broken Glass reminds us of the depths to which humanity can sink and the heights that the human spirit can reach. Steve Ross tells a remarkable story of survival and shows us how a person of good will and character can persevere through unspeakable tragedy and live a life of generosity and kindness."Frank S. HollemanIII, former U.S. Deputy Secretary of Education

-

"Steve Ross emerges as a resilient character who is determined not to allow the enemies of the past to re-emerge in the present unchallenged; his book opens with a cri de coeur on Charlottesville, and it ends with a defiant testimonial: 'I am a survivor.' A worthy memoir of dark times, full of practical lessons for resistance and community organizing today."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Throughout his childhood, Steve Ross was given every reason to hate, fear, and withdraw, but instead he has spent his life building a kinder, gentler, more hopeful world. You cannot read Steve's story and resist his contagious optimism for a better tomorrow."Congressman JoeKennedy III

-

"Inspiring...Ross's tale is darkly impressive....hope and resilience live within this man."The Improper Bostonian

-

"Steve Ross is a quiet leader for our city in the things we care about--helping people overcome obstacles, mentoring youth, providing the power of example....As he did this work, Ross brought people together across all kinds of historic boundaries--neighborhoods, races, religions. From Broken Glass is inspiring beyond words."Marty Walsh, Mayor of Boston

-

"A timely and beautiful book."Gary Shteyngart, New York Times bestselling author of Little Failure

-

"From Broken Glass is an opportunity to spend time in the presence of an extraordinary man. No one I know of has ever responded to unimaginable brutality with such generosity of deed and spirit, recounted here with understated eloquence."Congressman BarneyFrank, New York Times bestselling author of Frank: A Life in Politicsfrom the Great Society to Same-Sex Marriage

-

"Steve Ross's tireless work has helped ensure that the horrors of the Holocaust are never repeated."Israel Arbeiter,survivor of Auschwitz

-

"This moving memoir recounts how Ross, who was born Szmulek Rozental in Poland in 1931, created meaning for himself after the Holocaust..An inspirational account of hope overcoming horror."Publishers Weekly

-

"An introspective memoir about the power of perseverance and compassion....This account will inspire others to work in their communities to help the 'forgotten.'...a necessary and timely addition to Holocaust memoirs."Library Journal

- On Sale

- May 15, 2018

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316513081

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use