Promotion

Sign up for our newsletters to receive 20% off! Shop now. Exclusions apply.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

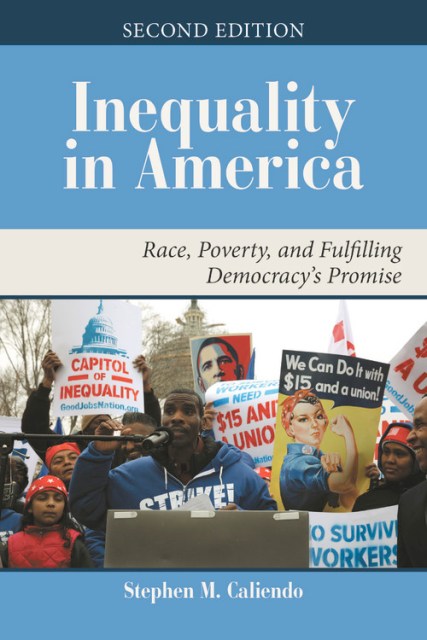

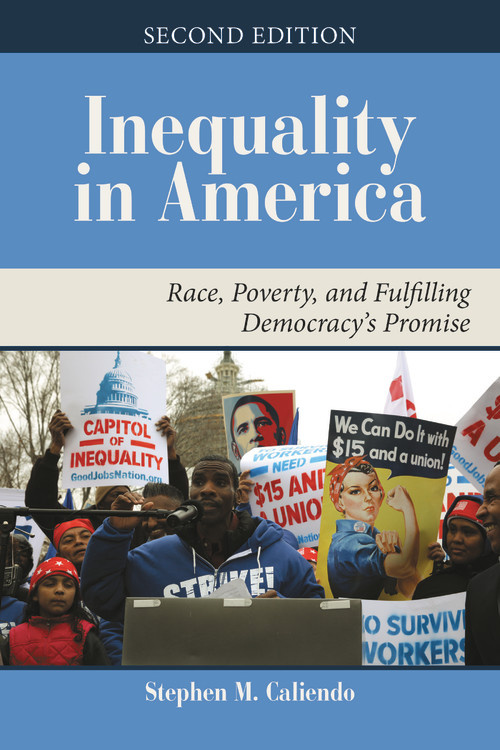

Inequality in America

Race, Poverty, and Fulfilling Democracy's Promise

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$33.00Format

Format:

- Trade Paperback $33.00

- ebook $19.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 18, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Why does inequality have such a hold on American society and public policy? And what can we, as citizens, do about it? Inequality in America takes an in-depth look at race, class and gender-based inequality, across a wide range of issues from housing and education to crime, employment and health. Caliendo explores how individual attitudes can affect public opinion and lawmakers’ policy solutions. He also illustrates how these policies result in systemic barriers to advancement that often then contribute to individual perceptions. This cycle of disadvantage and advantage can be difficult-though not impossible-to break. “Representing” and “What Can I Do?” feature boxes throughout the book highlight key public figures who have worked to combat inequality and encourage students to take action to do the same.

The second edition has been thoroughly revised to include the most current data and to cover recent issues and events like the 2016 elections and the Black Lives Matter movement. It now also includes a brand-new chapter on crime and criminal justice and an expanded discussion of immigration. Concise and accessible, Inequality in America paves the way for students to think critically about the attitudes, behaviors and structures of inequality.

- On Sale

- Jul 18, 2017

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Avalon Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780813350530

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use