Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

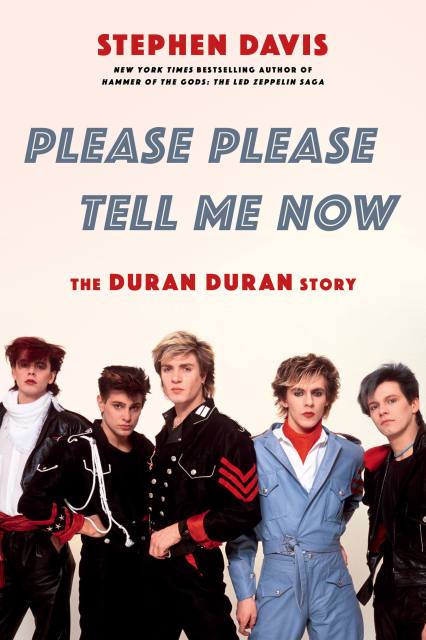

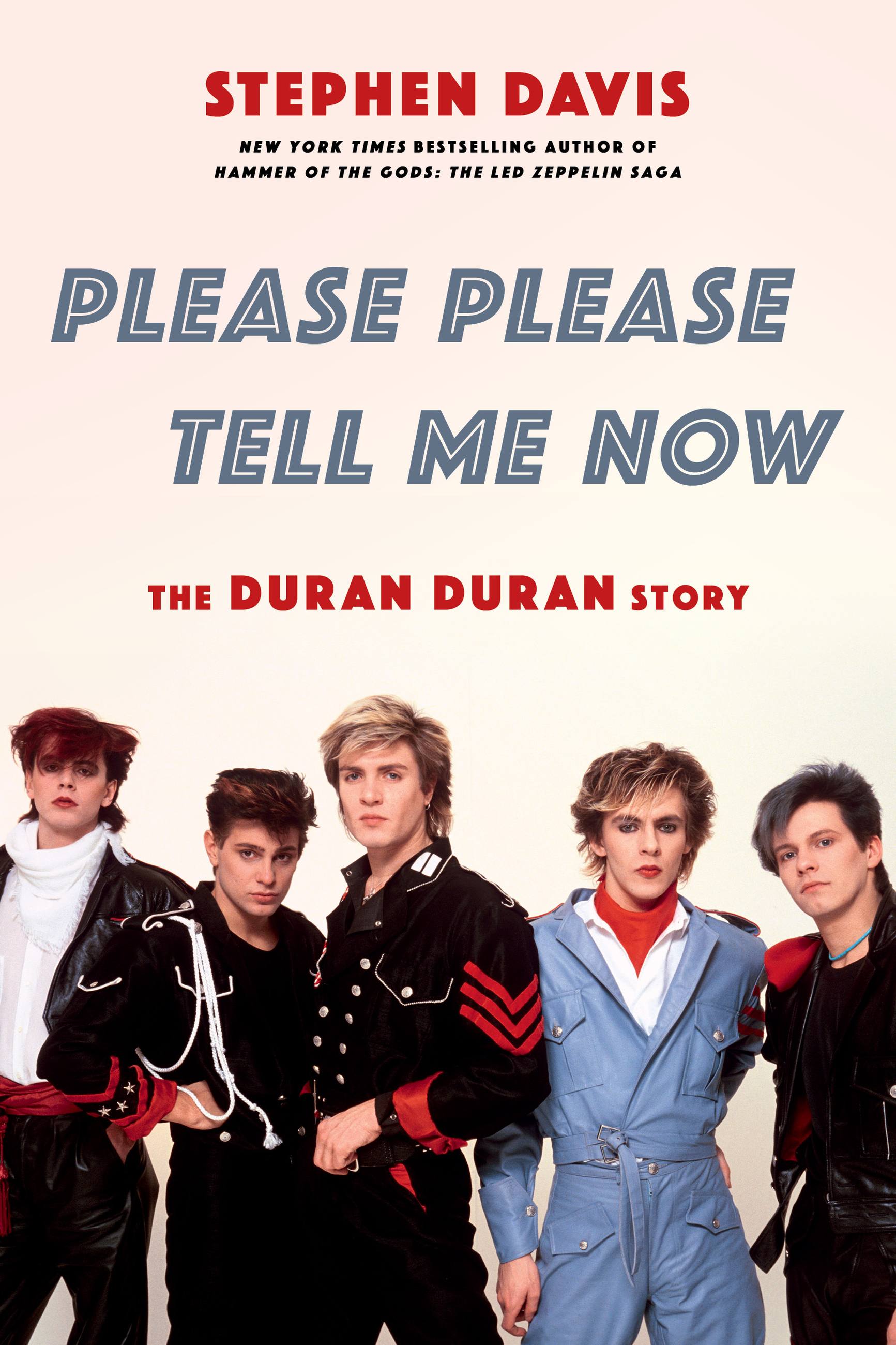

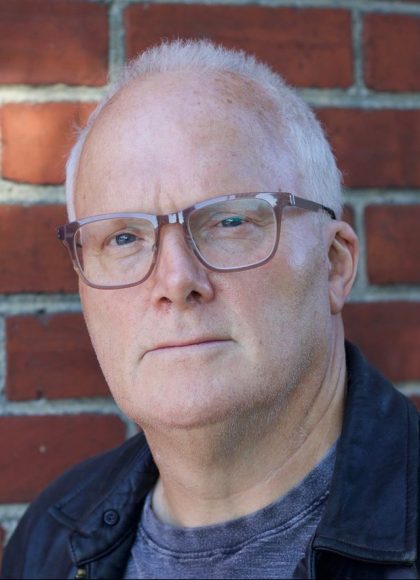

Please Please Tell Me Now

The Duran Duran Story

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$18.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 28, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In Please Please Tell Me Now, bestselling rock biographer Stephen Davis tells the story of Duran Duran, the quintessential band of the 1980s. Their pretty boy looks made them the stars of fledgling MTV, but it was their brilliant musicianship that led to a string of number one hits. By the end of the decade, they had sold 60 million albums; today, they've sold over 100 million albums—and counting.

Davis traces their roots to the austere 1970s British malaise that spawned both the Sex Pistols and Duran Duran—two seemingly opposite music extremes. Handsome, British, and young, it was Duran Duran that headlined Live Aid, not Bob Dylan or Led Zeppelin. The band moved in the most glamorous circles: Nick Rhodes became close with Andy Warhol, Simon LeBon with Princess Diana, and John Taylor dated quintessential British bad girl Amanda De Cadanet. With timeless hits like "Hungry Like the Wolf," "Girls on Film," "Rio," "Save a Prayer," and the bestselling James Bond theme in the series' history, "A View to Kill," Duran Duran has cemented its legacy in the pop pantheon—and with a new album and a worldwide tour on the way, they show no signs of slowing down anytime soon.

Featuring exclusive interviews with the band and never-before-published photos from personal archives, Please Please Tell Me Now offers a definitive account of one of the last untold sagas in rock and roll history—a treat for diehard fans, new admirers, and music lovers of any age.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jun 28, 2022

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780306846083

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use