Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

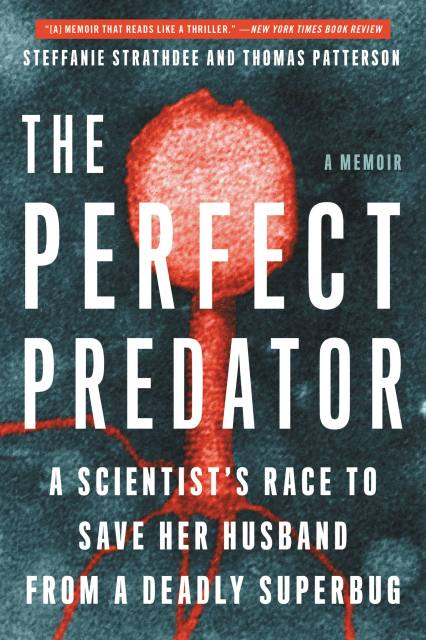

The Perfect Predator

A Scientist's Race to Save Her Husband from a Deadly Superbug: A Memoir

Contributors

With Teresa Barker

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $39.00 $49.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 26, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

“A memoir that reads like a thriller.” –New York Times Book Review

“A fascinating and terrifying peek into the devastating outcomes of antibiotic misuse–and what happens when standard health care falls short.” –Scientific AmericanEpidemiologist Steffanie Strathdee and her husband, psychologist Tom Patterson, were vacationing in Egypt when Tom came down with a stomach bug. What at first seemed like a case of food poisoning quickly turned critical, and by the time Tom had been transferred via emergency medevac to the world-class medical center at UC San Diego, where both he and Steffanie worked, blood work revealed why modern medicine was failing: Tom was fighting one of the most dangerous, antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the world.Frantic, Steffanie combed through research old and new and came across phage therapy: the idea that the right virus, aka “the perfect predator,” can kill even the most lethal bacteria. Phage treatment had fallen out of favor almost 100 years ago, after antibiotic use went mainstream. Now, with time running out, Steffanie appealed to phage researchers all over the world for help. She found allies at the FDA, researchers from Texas A&M, and a clandestine Navy biomedical center — and together they resurrected a forgotten cure.A nail-biting medical mystery, The Perfect Predator is a story of love and survival against all odds, and the (re)discovery of a powerful new weapon in the global superbug crisis.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Feb 26, 2019

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316418072

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use