Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

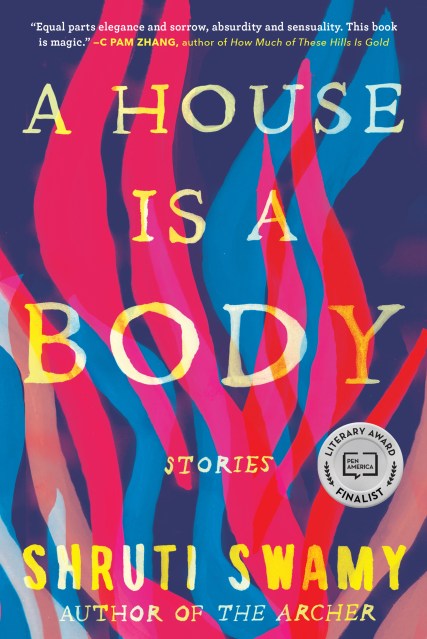

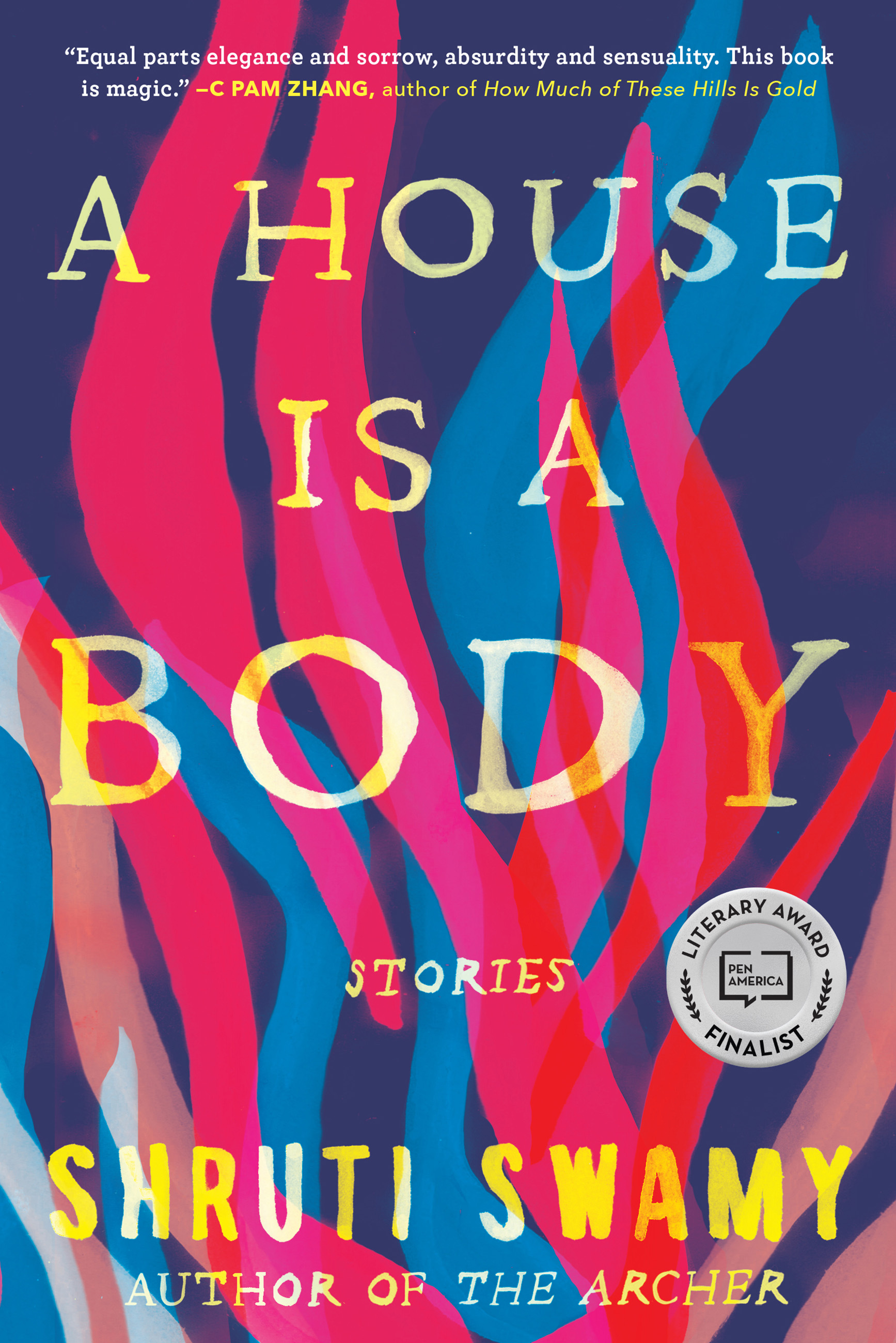

A House Is a Body

Stories

Contributors

By Shruti Swamy

Formats and Prices

Prices

- Sale Price $2.99

- Regular Price $10.99

- Discount (73% off)

Prices

- Sale Price $2.99 CAD

- Regular Price $13.99 CAD

- Discount (79% off)

Format

Format:

- ebook $2.99 $2.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $15.95 $21.95 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 11, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Finalist for the Los Angeles Times Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction

“A House Is a Body will not simply be talked about as one of the greatest short story collections of the 2020s; it will change the way all stories—short and long—are told, written, and consumed. There is nothing, no emotion, no tiny morsel of memory, no touch, that this book does not take seriously. Yet, A House Is a Body might be the most fun I’ve ever had in a short story collection.” —Kiese Laymon, author of Heavy

Dreams collide with reality, modernity with antiquity, and myth with identity in the twelve arresting stories of A House Is a Body. Set in the United States and India, Swamy’s characters grapple with motherhood, relationships, and their bodies to reveal small but intense internal moments of beauty, pain, and power that contain the world.

In “Earthly Pleasures,” a young painter living alone in San Francisco begins a secret romance with one of India’s biggest celebrities, and desire and ego are laid bare. In “A Simple Composition,” a husband’s professional crisis leads to his wife’s discovery of a dark, ecstatic joy. And in the title story, an exhausted mother watches, hypnotized by fear, as a California wildfire approaches her home. Immersive and assured, provocative and probing, these are stories written with the edge and precision of a knife blade.

A House Is a Body introduces a bold and original voice in fiction, from a writer at the start of a stellar career.

Don't miss Shruti Swamy's debut novel, The Archer (available September 7, 2021), which has already been longlisted for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize.

Genre:

-

An Electric Lit Favorite Short Story Collection of 2020

“A House Is A Body might be the most fun I've ever had in a short story collection.”

—Kiese Laymon, author of Heavy

“Stunning.”

—Ms.

“Swamy’s debut short story collection is rich, mesmeric . . . These are nuanced and quietly powerful stories about our most urgent and deeply felt experiences—grief, love, and desire.”

—BuzzFeed (29 Summer Books You Won't Be Able to Put Down)

“Equal parts elegance and sorrow, absurdity and sensuality. This book is magic.”

—C Pam Zhang, author of How Much of These Hills Is Gold

“Swamy connects the narratives through her clean prose, punctuating moments both surreal and eerily realistic.”

—Time ("Here Are the 12 New Books You Should Read in August")

“In this story collection that hops back and forth between India and the U.S., Shruti Swamy delivers a meticulous investigation of the pleasures, pains, and confusions that bodies afford—especially when those bodies belong to people of color. In the hypnotic, almost Lynchian title story (which previously appeared in The Paris Review), a Californian woman watches as a wildfire steadily advances on her home. These are closely observed stories that often turn into provocative studies about the absurdity of our entanglement with others.”

—The Millions

“Two-time O. Henry Award winner Shruti Swamy shows impressive range within the deceptively narrow confines (200 pages) of her debut short story collection, A House Is A Body . . . Swamy’s words readily dazzle, and the collection’s themes, including a haunting exploration of sibling rivalry, reveal themselves gradually.”

—The AV Club ("5 New Books to Read in August")

“The 12 stories that make up Shruti Swamy's A House Is a Body are mesmerizing in their richness . . . Swamy captures the full breadth of the human experience.”

—PopSugar ("26 Incredible New Books Coming Your Way This August")

“[Swamy] writes with sureness and grace. Her writing is more poetry than prose . . . The stories are rewarding for the elegance and lilt of the writing. Swamy takes you on an easy, well-articulated rides set in India, Germany, and the United States . . . If you love words, the way they can be used to describe objects and actions, the ways they can be assembled for effect, buy A House Is a Body. You will be rewarded.”

—New York Journal of Books

“The winner of two O. Henry Prizes, Shruti Swamy will publish her first short-story collection this summer, and you won't want to miss out on reading it. The 12 stories in A House Is a Body move between India and the U.S., focusing on women's interior lives and the ways in which their identities differ from the perceptions and presumptions of those around them.”

—Bustle

"Swamy’s pulsating prose produces riveting narratives. Her stories twist in subtle yet unexpected ways . . . The fallible characters in Swamy’s ravishing book are always falling into something and bravely grasping what they can on their way down in a frenetic attempt to pull themselves back up. A dazzling and exquisitely crafted collection."

—Kirkus Reviews, starred review

“Spanning the geographical and social distance between India and the U.S., Swamy’s 12 tales illuminate her characters’ imperfections and struggles, ultimately forming an attuned and mystical exploration into the enigmas of being human.”

—Booklist

"Swamy writes with a cool precision that draws the reader into her debut collection . . the plots unspool in lovely lucid prose that has a poetic omniscience . . . Swamy is off to a strong start."

—Publishers Weekly

“This is one of the books I'll turn to again and again, to study the tapestry of the prose, which is so beautiful and original. And there is such a deep curiosity at work here. I couldn't stop reading once I'd begun, couldn't part with this clear, exquisite, intelligent mind, contemplating an endlessly troubled and intimate world. It made me love reading all over again.”

—Rebecca Lee, author of Bobcat and Other Stories

“I’ve been reading Shruti Swamy’s stories for a long time and so for me to have them here together is cause for great celebration. These stories are written with such rare patience and a restraint that they are at times, almost unbearably tense. That’s a story writer. Not a book to read in a hurry. Take your time, as Swamy did. No need for hyperbole, either. The beauty and timeless grace of these stories will always speak for themselves.”

—Peter Orner, author of Maggie Brown Others: Stories

"Shruti Swamy writes with a confidence and rich understanding that recalls such renowned storytellers as Katherine Anne Porter and Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. Her collection A House is a Body is the perfect book for lovers of the short story and for all those willing to lose themselves in Swamy’s thoroughly developed fictional worlds. Shruti Swamy is a rare talent and A House is a Body is a gorgeous debut."

—Laura Furman, author of The Mother Who Stayed and former series editor of The O'Henry Prize Stories

"Powered by intense imagery and jolts of frank sexuality, Shruti Swamy’s A House Is a Body blurs the line between fantastical and naturalistic storytelling with its tales of love, loss, and life lived across cultures . . . mesmerizing."

—Foreword Reviews, starred review

- On Sale

- Aug 11, 2020

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Algonquin Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781643750606

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use