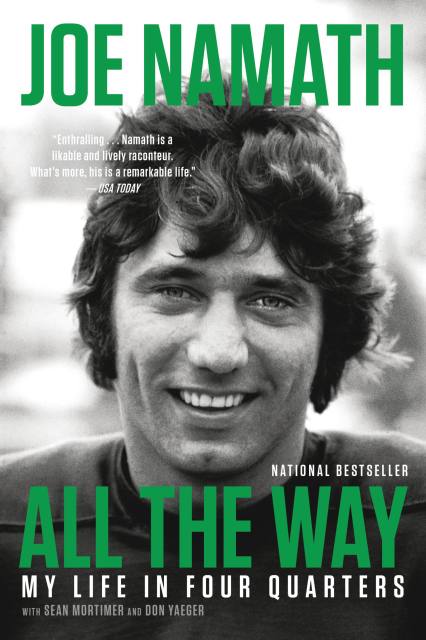

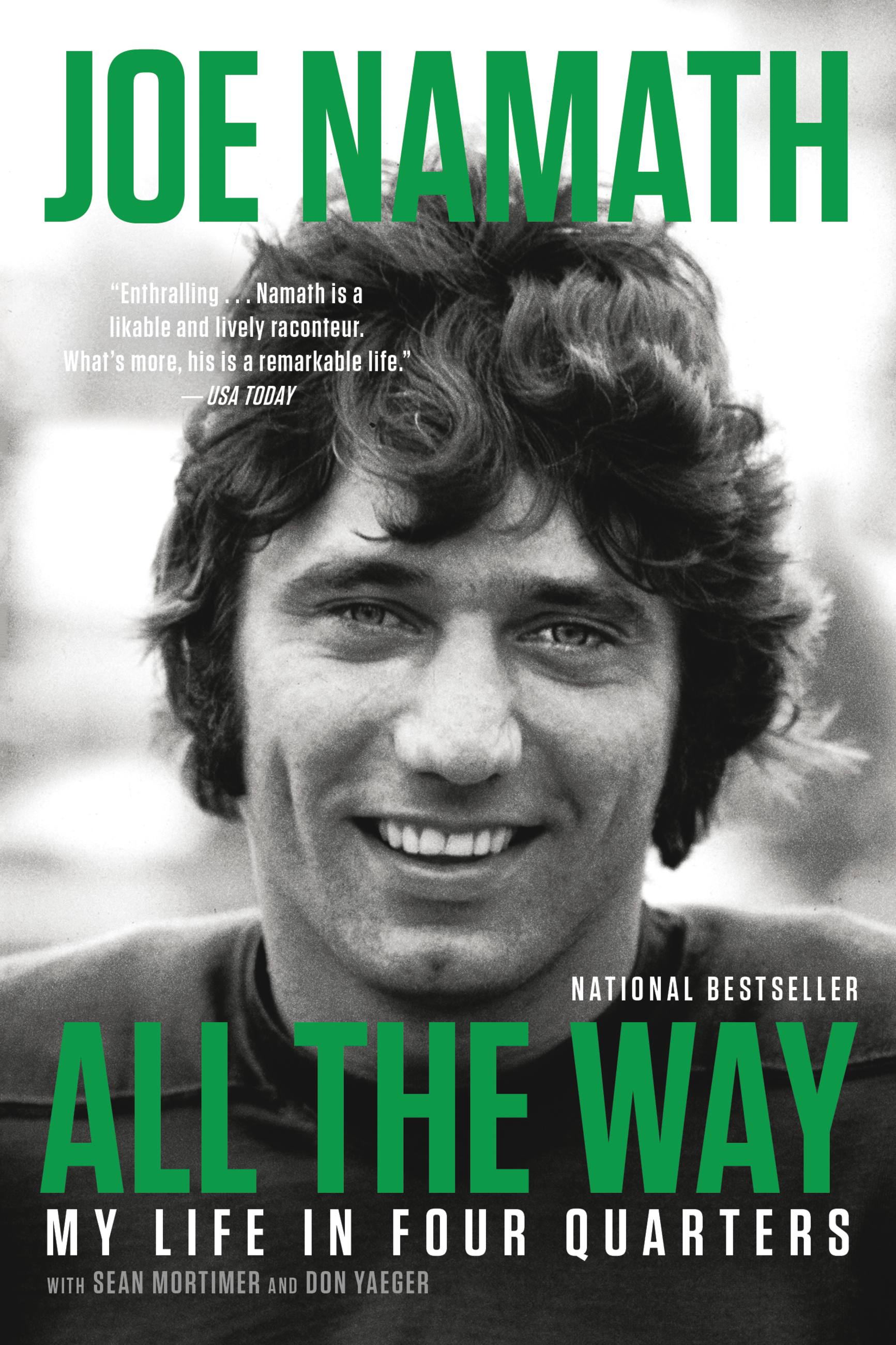

All the Way

My Life in Four Quarters

Contributors

With Sean Mortimer

With Don Yaeger

By Joe Namath

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 7, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Three days before the 1969 Super Bowl, Joe Namath promised the nation that he would lead the New York Jets to an 18-point underdog victory against the seemingly invincible Baltimore Colts. When the final whistle blew, that promise had been kept.

Namath was instantly heralded as a gridiron god, while his rugged good looks, progressive views on race, and boyish charm quickly transformed him – in an era of raucous rebellion, shifting social norms, and political upheaval – into both a bona fide celebrity and a symbol of the commercialization of pro sports. By 26, with a championship title under his belt, he was quite simply the most famous athlete alive.

Although his legacy has long been cemented in the history books, beneath the eccentric yet charismatic personality was a player plagued by injury and addiction, both sex and substance. When failing knees permanently derailed his career, he turned to Hollywood and endorsements, not to mention a tumultuous marriage and fleeting bouts of sobriety, to try and find purpose. Now 74, Namath is ready to open up, brilliantly using the four quarters of Super Bowl III as the narrative backbone to a life that was anything but charmed.

As much about football and fame as about addiction, fatherhood, and coming to terms with our own mortality, All the Way finally reveals the man behind the icon.

-

"Even casual sports fans will find this an enthralling read. For all his flaws - and the author does not hide them - Namath is a likable and lively raconteur. What's more, his is a remarkable life. He not only beat the Colts, he whooped alcoholism, evolved into a doting grandfather and endures the many side affects of gridiron fame with nary a complaint."USA Today

-

"So here we have it: a reflective football icon-76 years old, incredibly-and an elder statesman...he tells a good yarn, guaranteed."The Wall Street Journal

-

"As exciting as it is personal."247Sports

-

"I have read everything about Namath for years....But this new book is different, better than all of the ones before it in a sense. All the Way: My Life in Four Quarters is told in Namath's words. And those words are powerful and instructive.Ron Cook, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

-

"A pleasure for fans who remember way back to Namath's glory days-and an entertainment for those who are new to the gridiron hero."Kirkus

-

"Namath is refreshingly candid throughout...[his] razor-sharp recollections bring a bygone era of football to vivid life in this illuminating volume."Publishers Weekly

- On Sale

- May 7, 2019

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316421096

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use