Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

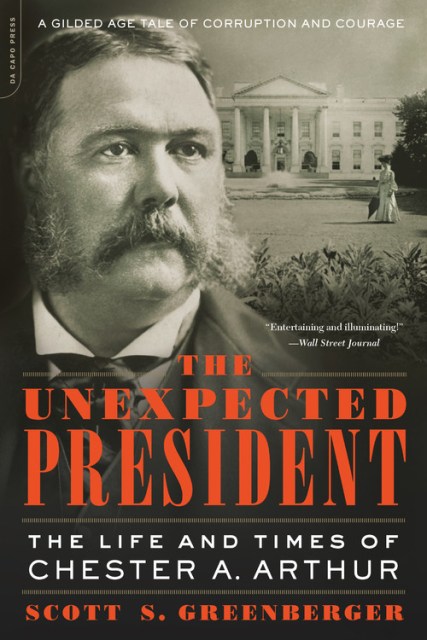

The Unexpected President

The Life and Times of Chester A. Arthur

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 4, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Despite his promising start as a young man, by his early fifties Chester A. Arthur was known as the crooked crony of New York machine boss Roscoe Conkling. For years Arthur had been perceived as unfit to govern, not only by critics and the vast majority of his fellow citizens but by his own conscience. As President James A. Garfield struggled for his life, Arthur knew better than his detractors that he failed to meet the high standard a president must uphold.

And yet, from the moment President Arthur took office, he proved to be not just honest but brave, going up against the very forces that had controlled him for decades. He surprised everyone — and gained many enemies — when he swept house and took on corruption, civil rights for blacks, and issues of land for Native Americans.

A mysterious young woman deserves much of the credit for Arthur’s remarkable transformation. Julia Sand, a bedridden New Yorker, wrote Arthur nearly two dozen letters urging him to put country over party, to find “the spark of true nobility” that lay within him. At a time when women were barred from political life, Sand’s letters inspired Arthur to transcend his checkered past–and changed the course of American history.

This beautifully written biography tells the dramatic, untold story of a virtually forgotten American president. It is the tale of a machine politician and man-about-town in Gilded Age New York who stumbled into the highest office in the land, only to rediscover his better self when his nation needed him.

Genre:

-

"Chester A. Arthur, who knew? Scott Greenberger redeems our most forgotten president from the margins of history with verve and narrative skill. Arthur lived a life full of twists. His biography is a story of a moral tumble and a brave quest for redemption. Greenberger propels us towards his subject, finding the pathos in his fascinating life, and quietly demands that we give him his proper due."--Franklin Foer, former editor of The New Republic and author of World Without Mind: The Existential Threat of Big Techand How Soccer Explains the World

-

"Shipwrecks. A crazed assassin. The frantic machinations of a deadlocked political convention. In this penetrating tale of madness, blundering, intrigue, and corruption at the height of the Gilded Age--that era that helped mold our own--Scott Greenberger gives us a keen and vivid portrait of President Chester Arthur, the most accidental of American chief executives, and the remarkable turns of fate that brought him to the White House."--John A. Farrell, author of Richard Nixon: The Life

-

"Scott Greenberger's sparkling narrative brings to life Chester Arthur's remarkable journey from lighthearted and cynical scion of New York's potent Republican machine to probity-minded president focused on the national interest. It's a poignant tale, as well as an important historical one, and it is captured here in vivid prose that dances upon a foundation of probing research."--Robert W. Merry, author of A Country of Vast Designs

-

"Scott S. Greenberger has crafted a riveting tale of nineteenth-century history from what others have skipped over as a mere historical curiosity. Crisply written and richly evocative, The Unexpected President is an inspiring account of how a political hack was transformed in meeting the expectation of the presidency and rendered a virtuous service to the nation. This is a remarkable work of historical discovery about a forgotten politician whose rise above the politics of his time could be a model for our age."--James McGrath Morris, author of Pulitzer: A Life in Politics, Print, and Power

-

"[Greenberger's] vibrant narrative and fetching personal profiles transform a biography about a largely overlooked political figure into a suspensefully, well, unexpectedly gratifying read."Sam Roberts, New York Times

-

"An entertaining, illuminating biography of the 21st president and the political world in which he lived."Wall Street Journal

-

"A great historical read and a great glimpse of a colorful, pivotal, oft-overlooked, slice of U.S. history."Austin American-Statesman

-

"Greenberger has done a fine job with what will likely be the definitive book on the 21st president."Houston Press

-

"Thoroughly accessible to lay readers and scholars alike...highly recommended."Midwest Book Review

-

"Richly researched, sourced and annotated, this book principally reveals a neglected president's varied career."Washington Times

-

"By sheer authorly enthusiasm, [Greenberger] manages to rescue Arthur from his own reputation as an obscure placeholder and put him before readers as a man who came abruptly into his own best convictions."Christian Science Monitor

-

"A solidly researched and fast-paced monograph that reminds us that there was more to Arthur than the sideburns."The Weekly Standard

-

"Greenberger convincingly presents a machine politician transformed by the responsibility of high office."Boston Globe

-

"An excellent page-turning biography."The Bowery Boys

-

"Greenberger employs his reportorial talent to tell a story with a strong narrative arc and makes Chester Arthur come alive on the page."The Bennington Banner

-

"[The Unexpected President] reminds readers of the importance of the choice for this office."Choice

- On Sale

- Jun 4, 2019

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306922701

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use