Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

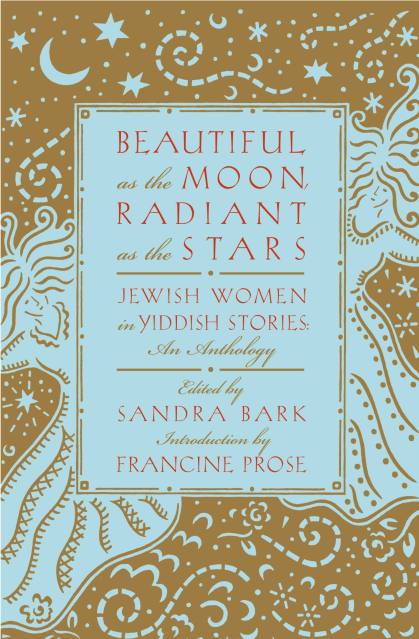

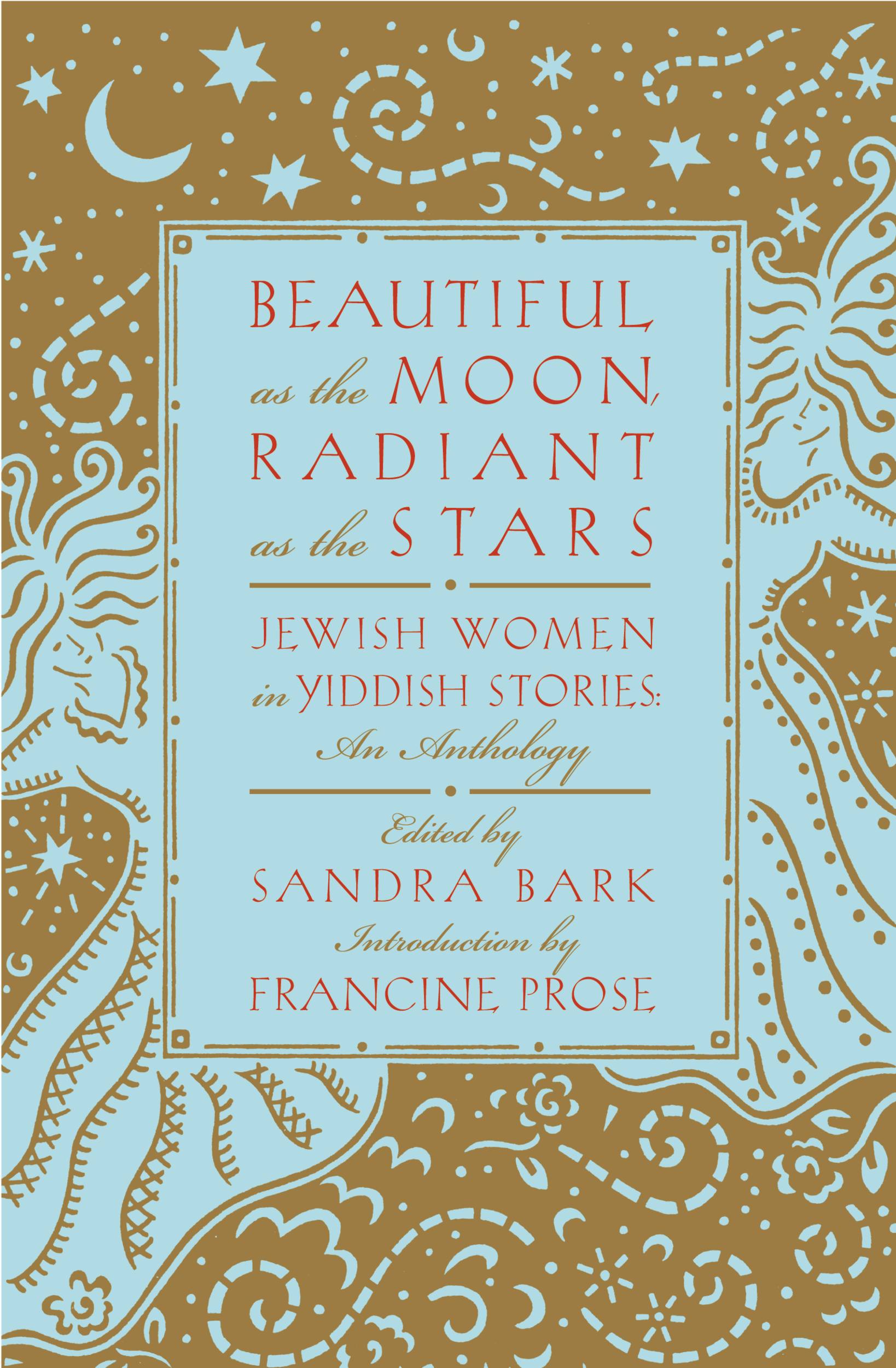

Beautiful as the Moon, Radiant as the Stars

Jewish Women in Yiddish Stories - An Anthology

Contributors

By Sandra Bark

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $9.99 $12.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 3, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

This book is certain to appeal to the millions of Jewish women interested in Jewish literature and the writings of Cynthia Ozick, Francine Prose, and Grace Paley. Beautifully packaged, it is an ideal Mother’s Day or Bat-Mitzvah gift.

This volume contains translations of Yiddish stories from eminent scholars–including an Isaac Bashevis Singer story that has never before been published in English–and well-known tales that Jewish readers everywhere love.

As bestsellers such as Everything is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer and For the Relief of Unbearable Urges by Nathan Englander have demonstrated, there is a strong interest in Jewish stories.

Yiddish culture and music have seen a resurgence in recent years. NPR’s All Things Considered aired a series of highly acclaimed documentaries about the Yiddish Radio Project and Klezmer musicians regularly play at top alternative venues.

This volume contains translations of Yiddish stories from eminent scholars–including an Isaac Bashevis Singer story that has never before been published in English–and well-known tales that Jewish readers everywhere love.

As bestsellers such as Everything is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer and For the Relief of Unbearable Urges by Nathan Englander have demonstrated, there is a strong interest in Jewish stories.

Yiddish culture and music have seen a resurgence in recent years. NPR’s All Things Considered aired a series of highly acclaimed documentaries about the Yiddish Radio Project and Klezmer musicians regularly play at top alternative venues.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 3, 2007

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780446510363

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use