Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

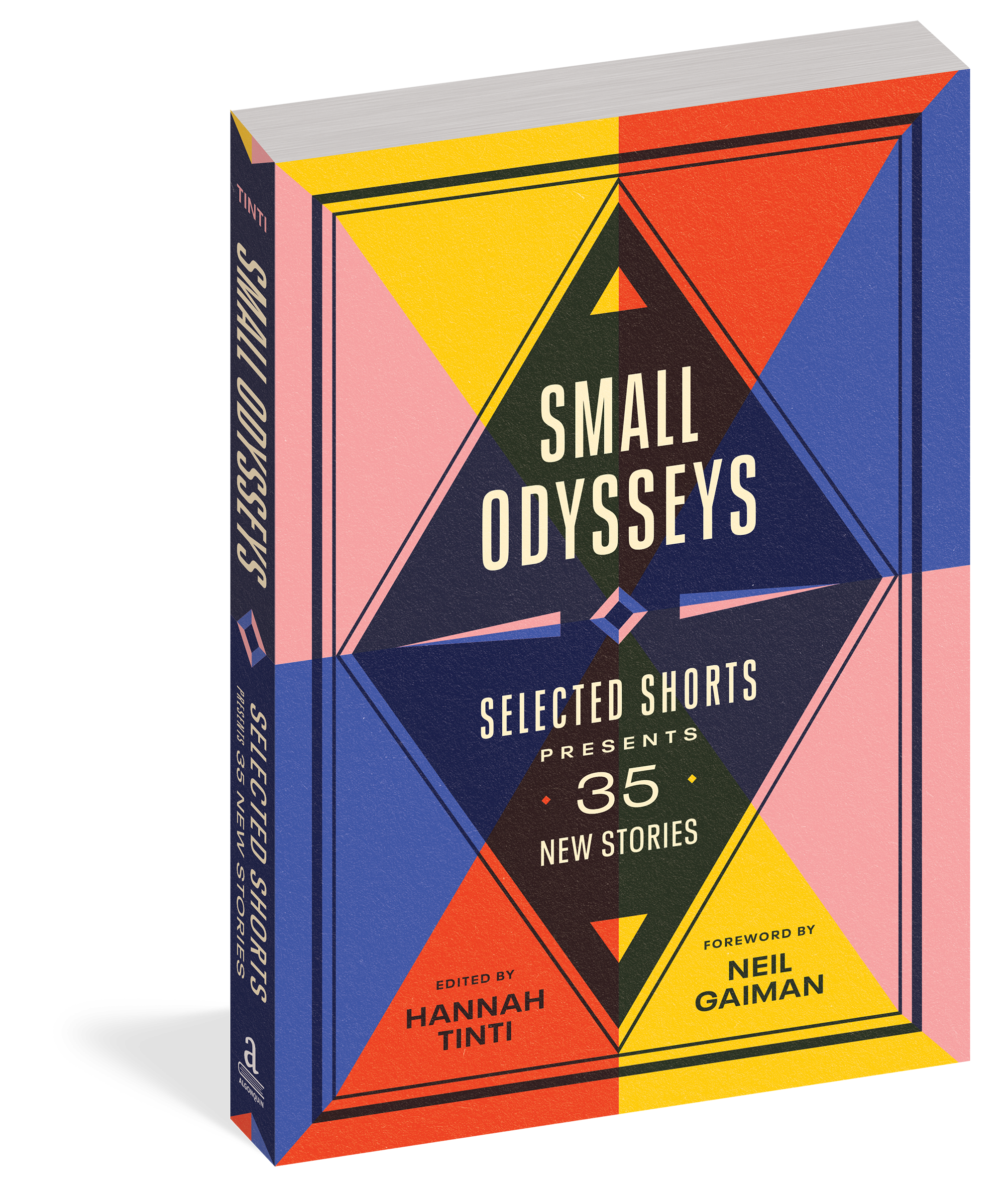

Small Odysseys

Selected Shorts Presents 35 New Stories

Contributors

Edited by Hannah Tinti

Foreword by Neil Gaiman

Formats and Prices

Price

$19.95Price

$24.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.95 $24.95 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 15, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

“Lovers of the short story, rejoice! There’s something for everyone in this anniversary collection . . . The collection makes the argument that time and again, it is stories that save us.” —Booklist

Thirty-five literary luminaries come together in this stunning collection of all-new works.

A must-have for any lover of literature, Small Odysseys sweeps the reader into the landscape of the contemporary short story, featuring never-before-published works by many of our most preeminent authors as well as up-and-coming superstars.

On their journey through the book, readers will encounter long-ago movie stars, a town full of dandelions, and math lessons from Siri. They will attend karaoke night, hear a twenty-something slacker’s breathless report of his failed recruiting by the FBI, and travel with a father and son as they channel grief into running a neighborhood bakery truck. They will watch the Greek goddess Persephone encounter the end of the world, and witness another apocalypse through a series of advertisements for a touchless bidet. And finally, they will meet an aging loner who finds courage and resilience hidden in the most unexpected of places—the next generation.

Published in partnership with beloved literary radio program and live show Selected Shorts in honor of its thirty-fifth anniversary, this collection of thirty-five stories captures its spirit in print for the first time.

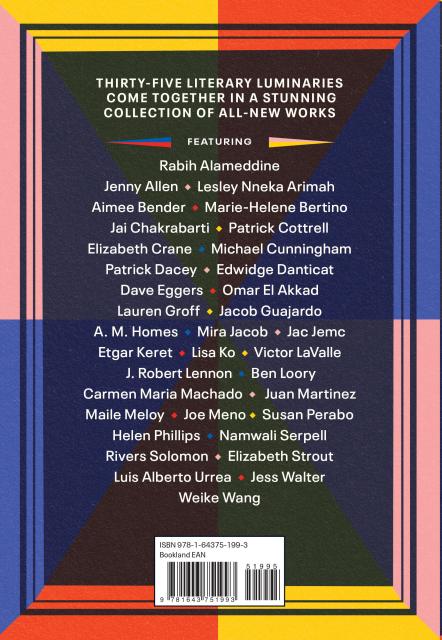

FEATURING

Rabih Alameddine * Jenny Allen * Lesley Nneka Arimah * Aimee Bender * Marie-Helene Bertino * Jai Chakrabarti * Patrick Cottrell * Elizabeth Crane * Michael Cunningham * Patrick Dacey * Edwidge Danticat * Dave Eggers * Omar El Akkad * Lauren Groff * Jacob Guajardo * A.M. Homes * Mira Jacob * Jac Jemc * Etgar Keret * Lisa Ko * Victor LaValle * J. Robert Lennon * Ben Loory * Carmen Maria Machado * Juan Martinez * Maile Meloy * Joe Meno * Susan Perabo * Helen Phillips * Namwali Serpell * Rivers Solomon * Elizabeth Strout * Luis Alberto Urrea * Jess Walter * Weike Wang

-

“Lovers of the short story, rejoice! There’s something for everyone in this anniversary collection . . . Author notes following each story add depth and understanding to these equally delightful and devastating literary ‘snacks’ . . . Overall, the collection makes the argument that time and again, it is stories that save us.”

—Booklist

“In her introduction, editor Hannah Tinti recalls the magic of listening to Selected Shorts on the radio in her early twenties . . . With Small Odysseys, she affords readers similar access to the transcendency of a story well-told.”

—Poets Writers

“Tinti delivers a dynamic anthology drawn from the Selected Shorts public radio program . . . Short story fans will enjoy the abundance of talent on offer.”

—Publishers Weekly

“A wide-ranging anthology of original stories from some of today's top authors . . . Well-curated, eclectic, and thoughtful.”

—Kirkus Reviews

- On Sale

- Mar 15, 2022

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Algonquin Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781643751993

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use