Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

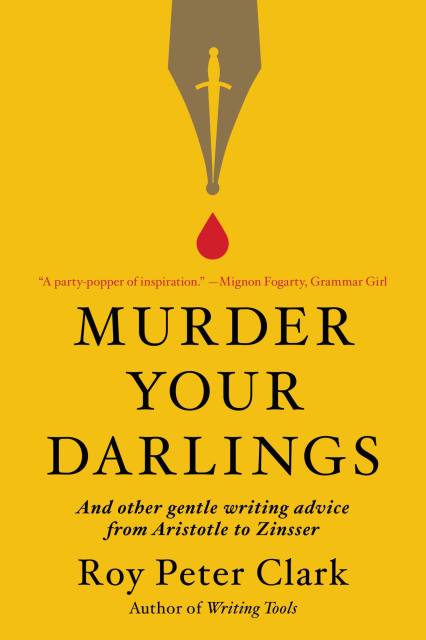

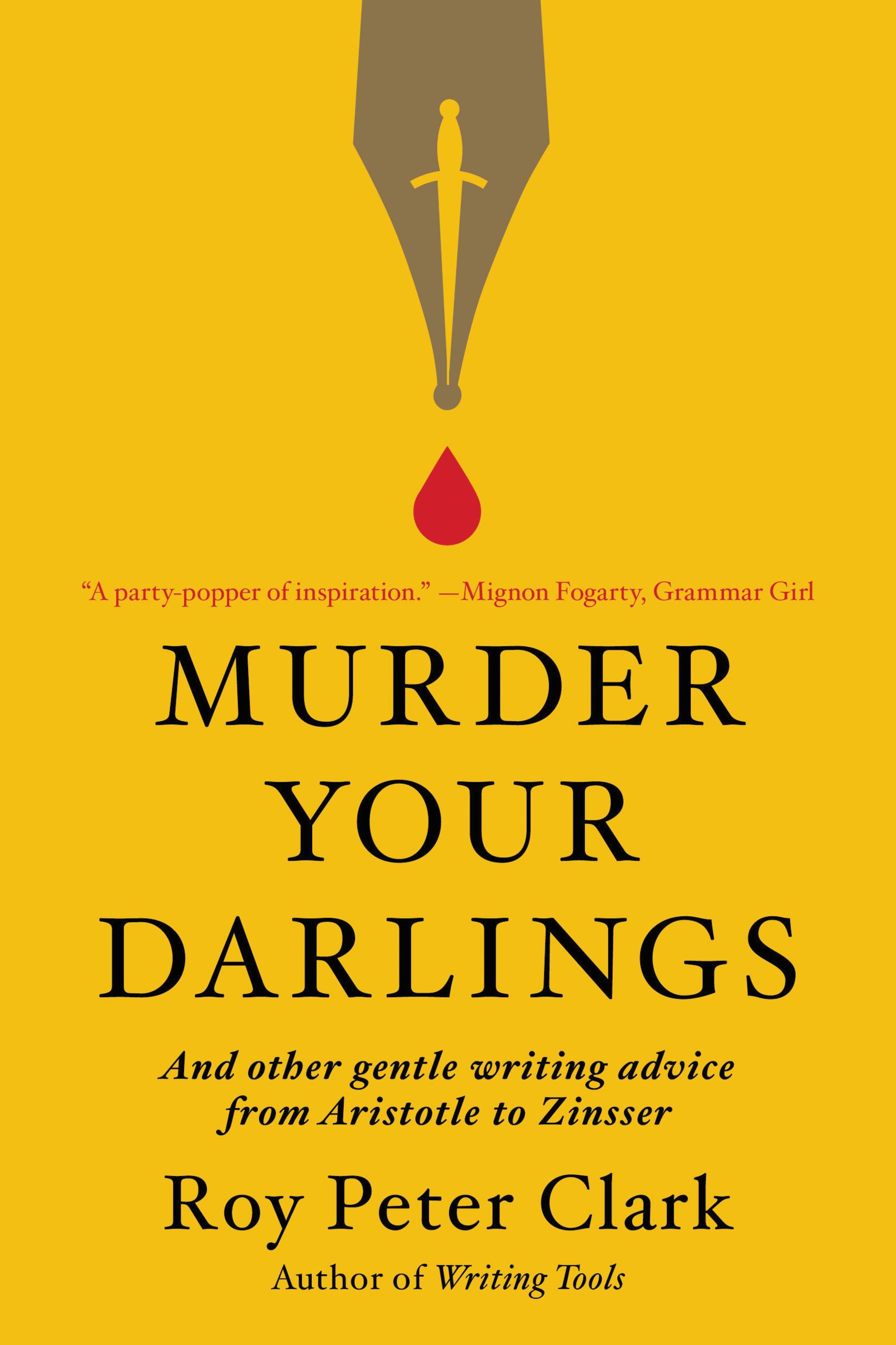

Murder Your Darlings

And Other Gentle Writing Advice from Aristotle to Zinsser

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 21, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

From one of America's most influential teachers, a collection of the best writing advice distilled from fifty language books — from Aristotle to Strunk and White.

With so many excellent writing guides lining bookstore shelves, it can be hard to know where to look for the best advice. Should you go with Natalie Goldberg or Anne Lamott? Maybe William Zinsser or Stephen King would be more appropriate. Then again, what about the classics — Strunk and White, or even Aristotle himself?

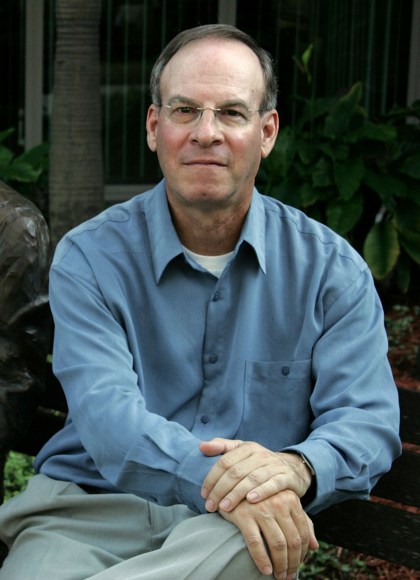

Thankfully, your search is over. In Murder Your Darlings, Roy Peter Clark, who has been a beloved and revered writing teacher to children and Pulitzer Prize winners alike for more than thirty years, has compiled a remarkable collection of more than 100 of the best writing tips from fifty of the best writing books of all time.

With a chapter devoted to each key strategy, Clark expands and contextualizes the original author's suggestions and offers anecdotes about how each one helped him or other writers sharpen their skills. An invaluable resource for writers of all kinds, Murder Your Darlings is an inspiring and edifying ode to the craft of writing.

With so many excellent writing guides lining bookstore shelves, it can be hard to know where to look for the best advice. Should you go with Natalie Goldberg or Anne Lamott? Maybe William Zinsser or Stephen King would be more appropriate. Then again, what about the classics — Strunk and White, or even Aristotle himself?

Thankfully, your search is over. In Murder Your Darlings, Roy Peter Clark, who has been a beloved and revered writing teacher to children and Pulitzer Prize winners alike for more than thirty years, has compiled a remarkable collection of more than 100 of the best writing tips from fifty of the best writing books of all time.

With a chapter devoted to each key strategy, Clark expands and contextualizes the original author's suggestions and offers anecdotes about how each one helped him or other writers sharpen their skills. An invaluable resource for writers of all kinds, Murder Your Darlings is an inspiring and edifying ode to the craft of writing.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jan 21, 2020

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Little Brown Spark

- ISBN-13

- 9780316481861

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use