Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

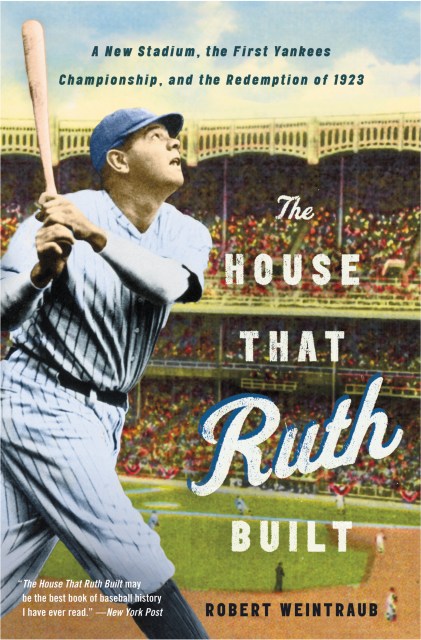

The House That Ruth Built

A New Stadium, the First Yankees Championship, and the Redemption of 1923

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 4, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The untold story of Babe Ruth’s Yankees, John McGraw’s Giants, and the extraordinary baseball season of 1923.

Before the 27 World Series titles — before Joe DiMaggio, Mickey Mantle, and Derek Jeter — the Yankees were New York’s shadow franchise. They hadn’t won a championship, and they didn’t even have their own field, renting the Polo Grounds from their cross-town rivals the New York Giants. In 1921 and 1922, they lost to the Giants when it mattered most: in October.

But in 1923, the Yankees played their first season on their own field, the newly-built, state of the art baseball palace in the Bronx called “the Yankee Stadium.” The stadium was a gamble, erected in relative outerborough obscurity, and Babe Ruth was coming off the most disappointing season of his career, a season that saw his struggles on and off the field threaten his standing as a bona fide superstar.

It only took Ruth two at-bats to signal a new era. He stepped up to the plate in the 1923 season opener and cracked a home run to deep right field, the first homer in his park, and a sign of what lay ahead. It was the initial blow in a season that saw the new stadium christened “The House That Ruth Built,” signaled the triumph of the power game, and established the Yankees as New York’s — and the sport’s — team to beat.

From that first home run of 1923 to the storybook World Series matchup that pitted the Yankees against their nemesis from across the Harlem River — one so acrimonious that John McGraw forced his Giants to get to the Bronx in uniform rather than suit up at the Stadium — Robert Weintraub vividly illuminates the singular year that built a classic stadium, catalyzed a franchise, cemented Ruth’s legend, and forever changed the sport of baseball.

Before the 27 World Series titles — before Joe DiMaggio, Mickey Mantle, and Derek Jeter — the Yankees were New York’s shadow franchise. They hadn’t won a championship, and they didn’t even have their own field, renting the Polo Grounds from their cross-town rivals the New York Giants. In 1921 and 1922, they lost to the Giants when it mattered most: in October.

But in 1923, the Yankees played their first season on their own field, the newly-built, state of the art baseball palace in the Bronx called “the Yankee Stadium.” The stadium was a gamble, erected in relative outerborough obscurity, and Babe Ruth was coming off the most disappointing season of his career, a season that saw his struggles on and off the field threaten his standing as a bona fide superstar.

It only took Ruth two at-bats to signal a new era. He stepped up to the plate in the 1923 season opener and cracked a home run to deep right field, the first homer in his park, and a sign of what lay ahead. It was the initial blow in a season that saw the new stadium christened “The House That Ruth Built,” signaled the triumph of the power game, and established the Yankees as New York’s — and the sport’s — team to beat.

From that first home run of 1923 to the storybook World Series matchup that pitted the Yankees against their nemesis from across the Harlem River — one so acrimonious that John McGraw forced his Giants to get to the Bronx in uniform rather than suit up at the Stadium — Robert Weintraub vividly illuminates the singular year that built a classic stadium, catalyzed a franchise, cemented Ruth’s legend, and forever changed the sport of baseball.

- On Sale

- Apr 4, 2011

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316175173

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use