Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

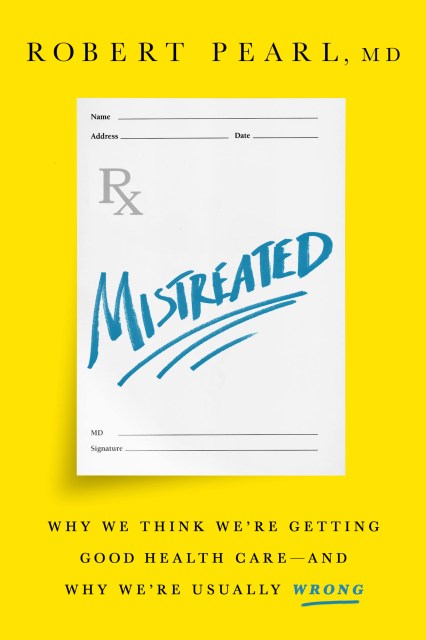

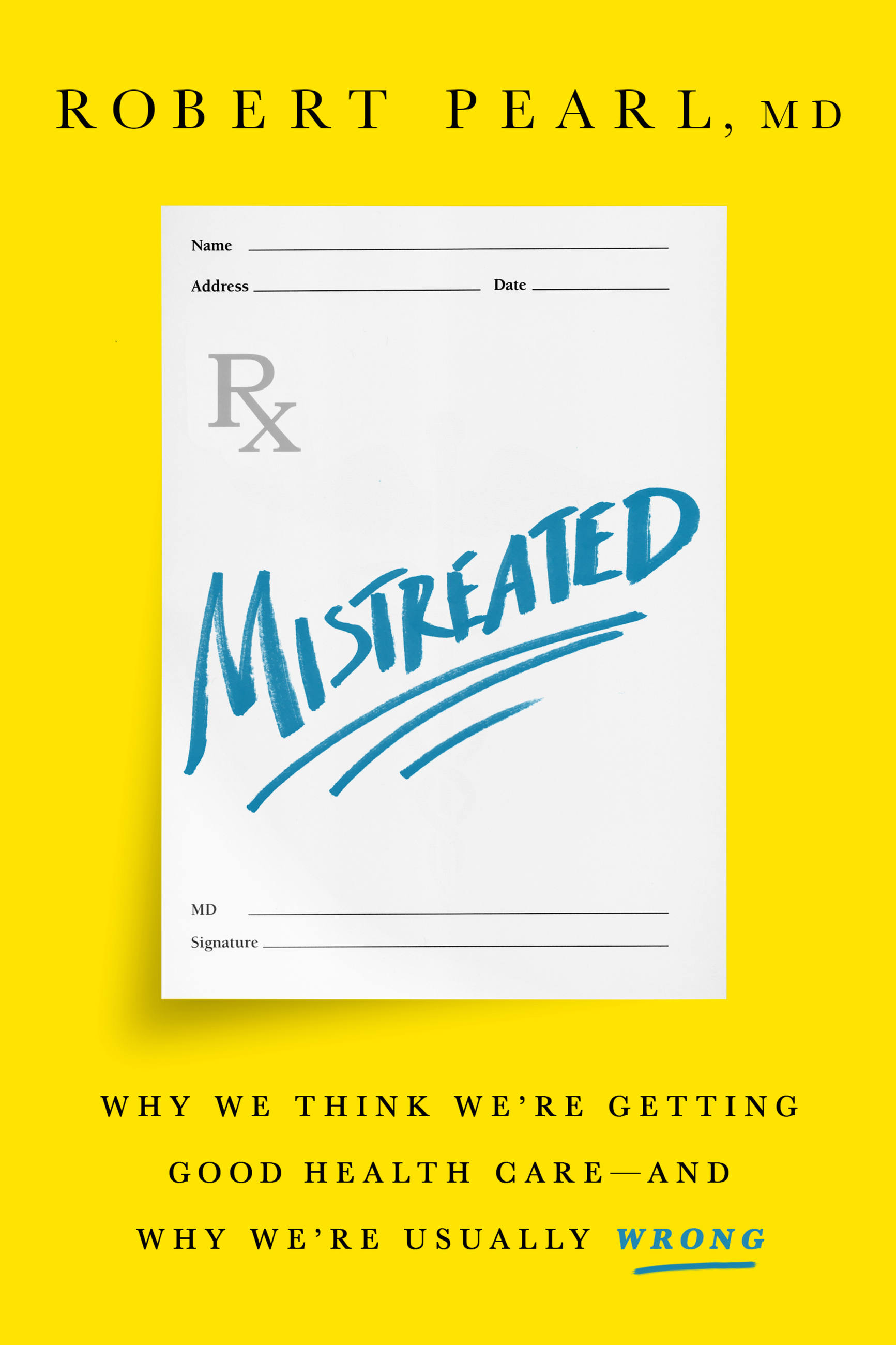

Mistreated

Why We Think We're Getting Good Health Care -- and Why We're Usually Wrong

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 2, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Do you know how to tell good health care from bad health care? Guess again. As patients, we wrongly assume the “best” care is dependent mainly on the newest medications, the most complex treatments, and the smartest doctors. But Americans look for health-care solutions in the wrong places. For example, hundreds of thousands of lives could be saved each year if doctors reduced common errors and maximized preventive medicine.

For Dr. Robert Pearl, these kinds of mistakes are a matter of professional importance, but also personal significance: he lost his own father due in part to poor communication and treatment planning by doctors. And consumers make costly mistakes too: we demand modern information technology from our banks, airlines, and retailers, but we passively accept last century’s technology in our health care.

Solving the challenges of health care starts with understanding these problems. Mistreated explains why subconscious misperceptions are so common in medicine, and shows how modifying the structure, technology, financing, and leadership of American health care could radically improve quality outcomes. This important book proves we can overcome our fears and faulty assumptions, and provides a roadmap for a better, healthier future.

Genre:

-

"Mistreated is a powerful read, an incredible insight into American health care, a mix of poignant personal memoir by a son, the clinical perspective of an experienced surgeon, and the vision and understanding that comes from being the CEO of one of the largest and best health care organizations in the country. Robert Pearl is all those things, and with Mistreated he proves he is also a wonderful writer."Abraham Verghese, MD, professor of medicine,Stanford University, and author of Cutting for Stone

-

"Robert Pearl argues that the troubles of the American health care system begin with a problem of perception: conceptual misunderstandings that warp priorities and distort choices. Mistreated is a brilliant and original analysis from one of medicine's most insightful leaders. The doctor is in."MalcolmGladwell, bestselling author of David and Goliath

-

"Mistreated is a timely and necessary book on how to fix our broken health system from one of our most important voices in health care. Dr. Robert Pearl's diagnosis isn't pretty. Morale in health care is low, costs are unmanageable, and health and survival are often worse than in other high-income countries. But Pearl is a leader who transformed his own health system to have very different results for patients and clinicians alike. And he offers that experience to show everyone the way."AtulGawande, bestselling author of Being Mortal

-

"Pundits like to speculate about the future of health care, but Dr. Robert Pearl has been busy creating it . . . at scale. As CEO of the nation's largest medical group, he and his colleagues at Kaiser Permanente have created a system serving 10 million members that is low cost, but with nation-leading quality outcomes and high patient satisfaction. They haven't just bent the cost curve, they've wrestled it into submission. If you want to understand how to fix health care, listen to him: he knows."Chip Heath, coauthor of Switch and Decisive

-

"Relying on his long history as one of the country's most innovative and powerful physician-leaders, Dr. Robert Pearl lays bare the shortsightedness of the broken US health care system: why we resist better science, newer technology, and reform. He offers a vision of how to improve our medical care, informed and tested in his own real world practice."-Elisabeth Rosenthal, editor in chief of Kaiser HealthNews

-

"Drawing on psychological research and his diverse roles as physician, business professor, and chief executive, Dr. Pearl diagnoses the problems of the American health care system and offers simple yet important solutions. In a health care system undergoing rapid changes, Mistreated is an essential and trusted guide to the future."EzekielJ. Emanuel, author of Reinventing American Health Care

-

"Mistreated is the honest conversation we need to have about the beautiful but broken craft of medicine."Marty Makary, MD, New York Times-bestselling authorof Unaccountable

-

"A respected expert gets personal. The result is a gripping drama set in our troubled health care system-and happily a roadmap for fixing it."CeciConnolly, president and CEO of the Alliance of Community Health Plans

-

"This is an important book. With clear and engaging examples, Mistreated reviews the fl aws in our traditional fragmented health care system, showing that context and perception matter more in health care than logic and data. This powerful insight can help our nation transform American medicine and make it the best in the world. A must-read for anyone who has ever been or will be a patient-and that is all of us."AlainEnthoven, professor emeritus, Graduate School of Business at Stanford

-

"Mistreated provides a poignant and powerful portrait of what causes our health system to fail despite our best intentions. Starting with the painful story of his father's untimely death due to medical error, Dr. Pearl honors his father's memory by teaching us how to build a system that creates health and prevents harm."Ian Morrison, PhD, author, consultant, and futurist

-

"Dr. Pearl combines facts, evidence, and real-life experiences that demystify the complex American health care system and offer ways to improve it. His vast and varied experiences in medicine lend particular weight to his ideas for constructive change."JohnIglehart, founding editor of Project HOPE

- On Sale

- May 2, 2017

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610397667

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use