Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

Storynomics

Story-Driven Marketing in the Post-Advertising World

Contributors

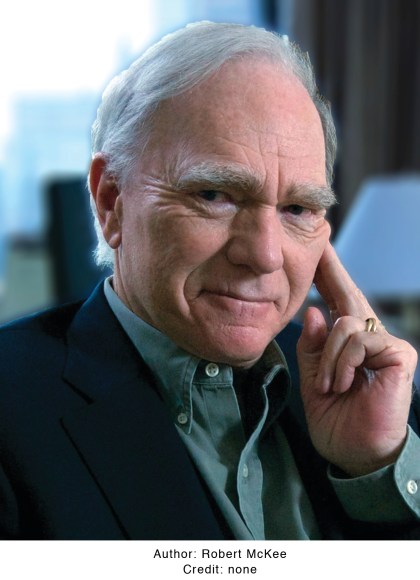

By Robert Mckee

By Thomas Gerace

Formats and Prices

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $39.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 20, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Based on the hottest, most in-demand seminar offered by the legendary story master Robert McKee — Storynomics translates the lessons of storytelling in business into economic and leadership success.

Robert McKee’s popular writing workshops have earned him an international reputation. The list of alumni with Academy Awards and Emmy Awards runs off the page. The cornerstone of his program is his singular book, Story, which has defined how we talk about the art of story creation.

Now in Storynomics, McKee partners with digital marketing expert and Skyword CEO Tom Gerace to map a path for brands seeking to navigate the rapid decline of interrupt advertising. After successfully guiding organizations as diverse as Samsung, Marriott International, Philips, Microsoft, Nike, IBM, and Siemens to transform their marketing from an ad-centric to story-centric approach, McKee and Gerace now bring this knowledge to business leaders and entrepreneurs alike.

Drawing from dozens of story-driven strategies and case studies taken from leading B2B and B2C brands, Storynomics demonstrates how original storytelling delivers results that surpass traditional advertising. How will brands and their customers connect in the future? Storynomics provides the answer.

Robert McKee’s popular writing workshops have earned him an international reputation. The list of alumni with Academy Awards and Emmy Awards runs off the page. The cornerstone of his program is his singular book, Story, which has defined how we talk about the art of story creation.

Now in Storynomics, McKee partners with digital marketing expert and Skyword CEO Tom Gerace to map a path for brands seeking to navigate the rapid decline of interrupt advertising. After successfully guiding organizations as diverse as Samsung, Marriott International, Philips, Microsoft, Nike, IBM, and Siemens to transform their marketing from an ad-centric to story-centric approach, McKee and Gerace now bring this knowledge to business leaders and entrepreneurs alike.

Drawing from dozens of story-driven strategies and case studies taken from leading B2B and B2C brands, Storynomics demonstrates how original storytelling delivers results that surpass traditional advertising. How will brands and their customers connect in the future? Storynomics provides the answer.

Genre:

-

PRAISE FOR STORYNOMICS AND ROBERT MCKEEp.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Helvetica Neue'; color: #454545}Simon Mulcahy, Chief Marketing Officer, Salesforce

"Essential reading for any company looking to build a loyal audience through great storytelling." -

"Storynomics should be required training for every marketer -- regardless of level or industry. It is truly a special treat to learn from these masters of storytelling."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Helvetica Neue'; color: #454545}David Beebe, Emmy-winning Producer, Brand Storyteller; Former VP, Global Creative and Content Marketing & Founder of Marriott Content Studio, Marriott International

-

"We have worked with Robert McKee for over five years and his Storynomics techniques have opened the door to our innovation and growth. A must read!"p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Helvetica Neue'; color: #454545}Robert J. DeKoch, President & COO, The BOLDT Company

-

"If you want a clear and concise look at how modern brands are connecting with their customers today, Storynomics is it."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Helvetica Neue'; color: #454545}Brian Moody, Executive Editor, Autotrader

-

"Some look at recent upheavals in the marketing landscape and see shrinking opportunities, rising costs, and distracted, indifferent audiences. Storynomics is written for another group: those who see in these changes an opportunity to tell a deeper, more personal story to their audiences."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Helvetica Neue'; color: #454545}Pat Partridge, Chief Marketing Officer, Western Governors University

-

"McKee is the world's best-known and most respected lecturer of Storytelling Arts."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Helvetica Neue'; color: #454545}Wall Street Journal

-

"McKee and Gerace are storytelling whizzes who give great advice and great supporting stories. Their tips and recommendations are simple to follow with a step-by-step methodology."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Helvetica Neue'; color: #454545}Eduardo Arteaga, AVP of Digital Marketing, US Bancorp

-

"Between ad blockers, skippable commercials, and everything in between, marketers need to evolve to market in a form that is accepted by potential customers. Storynomics provides a blueprint marketing strategy that helps you connect to your audience in a meaningful way."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Helvetica Neue'; color: #454545}Jessica Snavely, Director Performance Marketing, Automattic

- On Sale

- Mar 20, 2018

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781455541973

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use