Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

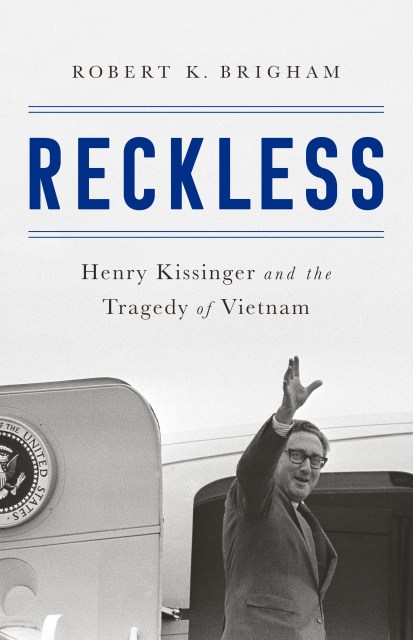

Reckless

Henry Kissinger and the Tragedy of Vietnam

Contributors

Read by Jeff Bottoms

Formats and Prices

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Hardcover $37.00 $47.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 4, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The American war in Vietnam was concluded in 1973 after eight years of fighting, bloodshed, and loss. Yet the terms of the truce that ended the war were effectively identical to what had been offered to the Nixon administration four years earlier. Those four years cost America and Vietnam thousands of lives and billions of dollars, and they were the direct result of the supposed master plan of the most important voice in American foreign policy: Henry Kissinger.

Using newly available archival material from the Nixon Presidential Library, Kissinger’s personal papers, and material from the archives in Vietnam, Robert K. Brigham punctures the myth of Kissinger as an infallible mastermind. Instead, he constructs a portrait of a rash, opportunistic, and suggestible politician. It was personal political rivalries, the domestic political climate, and strategic confusion that drove Kissinger’s actions. There was no great master plan or Bismarckian theory that supported how the US continued the war or conducted peace negotiations. Its length was doubled for nothing but the ego and poor judgment of a single figure.

This distant tragedy, perpetuated by Kissinger’s actions, forever changed both countries. Now, perhaps for the first time, we can see the full scale of that tragedy and the machinations that fed it.

Genre:

-

"One of the most compelling elements of the book is Brigham's portrayal of Kissinger's manipulation of an emotionally insecure Nixon. The president often responded by expressing doubts about Kissinger's methods, but he did Kissinger's bidding more often than not out of desperation to win over the American electorate during the 1972 election cycle."Kirkus Reviews

-

"A welcome, much-needed reexamination of the secret negotiations that led to America's withdrawal from the Vietnam War. Using impressive new research, Robert K. Brigham skillfully analyzes the origins of the 1973 Paris Agreement and persuasively debunks the myth of Henry Kissinger as a diplomat of rare ability."George C. Herring, author of America's Longest War: The United States andVietnam, 1950-1975

-

"Robert K. Brigham, drawing on many previously unpublished official transcripts and records, makes a scholarly and convincing case that Henry Kissinger's policymaking on Vietnam during the Nixon Administration was 'reckless.' Both in the secret peace negotiations with the North Vietnamese in Paris and in ordering massive bombing raids on their forces in Cambodia and Laos, and on Hanoi itself, Kissinger was ignorant of their determination to reunite their country at all costs. Ultimately, with no consultation with the US-supported regime in Saigon, he negotiated a peace agreement that freed US prisoners of war and completed the American military withdrawal in 1973, but allowed North Vietnamese military forces to remain in territory they had occupied in South Vietnam-dooming it, as President Nguyen Van Thieu knew it would, to defeat, which came two years later."Craig R. Whitney, Saigon correspondent andbureau chief of the New York Times,1971-1973

-

"Brigham offers a persuasive argument that [Kissinger] lied, misled, and deceptively outmaneuvered other policy makers in setting Vietnam War policy from 1969 to 1975, with disastrous results.... This all-but-total condemnation...confirms what many Kissinger skeptics have believed for decades and may change the minds of some who have believe him to be a foreign policy guru."Publishers Weekly

-

"Vietnam-era scholars and informed audiences fascinated by Kissinger will welcome the author's insights."Library Journal

-

"Brigham makes a strong case that Kissinger's war policy-making was 'a total failure'....Making good use of new primary source material...he destroys Kissinger's carefully and deceptively cultivated image as a foreign policy guru....[Reckless] should change the minds of those who have believed Kissinger's deceptive, self-aggrandizing re-writing of Vietnam War history."Vietnam Veterans of America Magazine

-

"It's a clapback 15 years in the making, and offers insight into how Kissinger's machinations were less brilliance than guesswork and ego, with disastrous results....[Reckless] squarely assigns the blame."Progressive Populist

- On Sale

- Sep 4, 2018

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781549142123

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use