Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

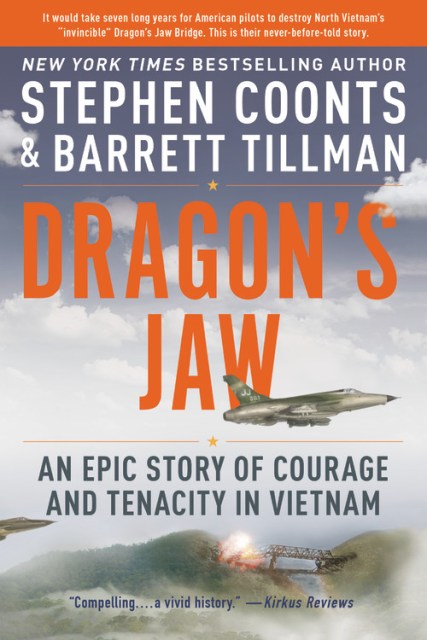

Dragon's Jaw

An Epic Story of Courage and Tenacity in Vietnam

Contributors

By Barrett Tillman

Formats and Prices

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 11, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Every war has its "bridge"–Old North Bridge at Concord, Burnside's Bridge at Antietam, the railway bridge over Burma's River Kwai, the bridge over Germany's Rhine River at Remagen, and the bridges over Korea's Toko Ri. In Vietnam it was the bridge at Thanh Hoa, called Dragon's Jaw. For many years hundreds of young US airmen flew sortie after sortie against North Vietnam's formidable and strategically important bridge, dodging a heavy concentration of anti-aircraft fire, surface-to-air missiles and enemy fighters. Many American airmen were shot down, killed, or captured and taken to the infamous POW prisons in Hanoi. But after each air attack, when the smoke cleared and the debris settled, the bridge stubbornly remained standing. For the North Vietnamese it became a symbol of their invincibility; for US war planners an obsession; for US airmen a testament to American mettle and valor. Using after-action reports, official records, and interviews with surviving pilots, as well as previously untapped Vietnamese sources, Dragon's Jaw chronicles American efforts to destroy the bridge, strike by bloody strike, putting readers into the cockpits, under fire. The story of the Dragon's Jaw is a story rich in bravery, audacity, sometimes luck and sometimes tragedy. The "bridge" story of Vietnam is an epic tale of war against a determined foe.

Genre:

-

"Master military storytellers Coonts and Tillman have impressively combined their literary firepower to craft a detailed and eminently readable tale about the long sought take-down of the notorious Thanh Hoa Bridge. Dragon'sJaw reads like the powerful thriller that it is--but it's no fiction!"Christina Olds, coauthor of Fighter Pilot

-

"Vietnam War naval aviator Stephen Coonts and top military historian Barrett Tillman describe the long bombing campaign against one of the hardest targets in history, the Thanh Hoa Bridge. Almost mystically preserved after years of attacks, the bridge ultimately fell to American courage, skill, and persistence. This book is especially valuable for its presentation of the Vietnamese point of view."Colonel Walter J. Boyne, USAF (Ret), former direction of the National Air and Space Museum

-

"In this path-breaking book, Vietnam A-6 Intruder pilot Stephen Coonts and noted military aviation historian Barrett Tillman have joined their formidable backgrounds and skills to lay bare the underlying strategy, planning, and execution of the campaign-within-an-air campaign to drop this formidable and deadly target. Readers will learn what it was like to fly against it, the price America paid in lost and captured airmen and destroyed airplanes, and the bankruptcy and lasting efforts of Johnson-era Vietnam strategy."Dr. Richard P. Hallion, aerospace historian and former Historian of the US Air Force

-

"A powerful story about the quest to drop the Thanh Hoa Bridge during the Vietnam War and how Washington made it even more challenging for our aircrews. Riveting action! Unmatched authenticity as Steve Coonts flew many harrowing missions in that war. A must-read for all naval aviators, past, present, and future!"Admiral Jay L. Johnson, USN (Ret), Vietnam F-8 pilot and former Chief of Naval Operations

-

"The Thanh Hoa Bridge is emblematic of the American experience in Vietnam. The bridge's mythical status arose from years of failed attempts to destroy it, as well as the tenacious Vietnamese defenses surrounding it. It's all here—the professionalism, the sacrifice, the maddening political decision-making, and even Vietnamese accounts. This book has it all, in a manner that made Flight of the Intruder and On Yankee Station famous!"Peter Fey, author of Bloody Sixteen: The USS Oriskany and Air Wing 16 During the Vietnam War

-

“A vivid history of the long campaign against the Dragon’s Jaw Bridge; especially recommended for aficionados of air warfare.”Kirkus Reviews

- On Sale

- May 11, 2021

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780306903458

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use