Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

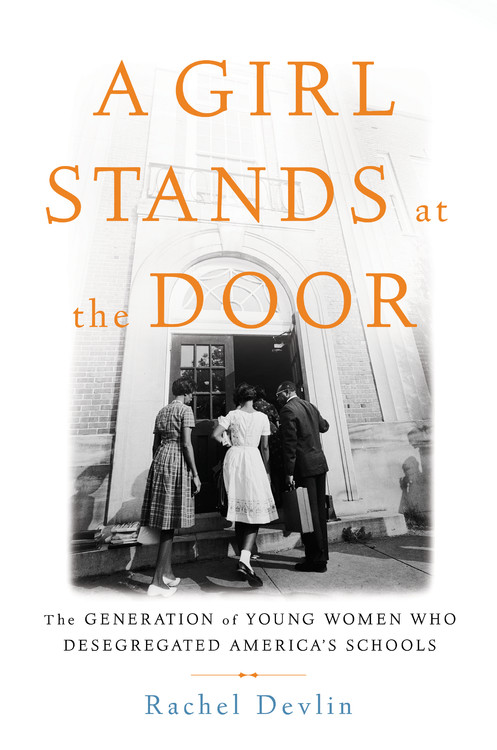

A Girl Stands at the Door

The Generation of Young Women Who Desegregated America's Schools

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$32.00Price

$40.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $32.00 $40.00 CAD

- ebook $19.99 $24.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 15, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A new history of school desegregation in America, revealing how girls and women led the fight for interracial education

The struggle to desegregate America’s schools was a grassroots movement, and young women were its vanguard. In the late 1940s, parents began to file desegregation lawsuits with their daughters, forcing Thurgood Marshall and other civil rights lawyers to take up the issue and bring it to the Supreme Court. After the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, girls far outnumbered boys in volunteering to desegregate formerly all-white schools.

In A Girl Stands at the Door, historian Rachel Devlin tells the remarkable stories of these desegregation pioneers. She also explains why black girls were seen, and saw themselves, as responsible for the difficult work of reaching across the color line in public schools. Highlighting the extraordinary bravery of young black women, this bold revisionist account illuminates today’s ongoing struggles for equality.

Genre:

-

"Revelatory...Devlin reminds us that the task of publicly and constitutionally challenging racial discrimination in education was laid on the bodies of black girls. This is a reality with which America has yet to reckon."New York Times Book Review

-

"[A] groundbreaking new work of recovered history...Devlin, a Rutgers University historian, spent ten years tracking down and interviewing dozens of women who endured harassment and abuse to desegregate schools, whether or not their lawsuits prevailed...Devlin's chronicle...promises to reignite public conversation and debate about racial disparities in public education."Smithsonian

-

"Fascinating...Devlin is the first historian to demonstrate that, collectively, girls were the vanguard of the struggle against Jim Crow in education"New York Review of Books

-

"Meticulous and emotionally resonant...Devlin paints compelling portraits of largely unknown desegregation pioneers...Her interviews with the many 'firsts'...are riveting, inspiring and dispiriting."Ms.

-

"In her sweeping analysis...Devlin makes it clear what was at stake for these girls and why we must continue to remember their sacrifices."Bitch Magazine

-

"This is essential American history-it's the history of how we got where we are, it's a history of how student activism changed the world by fighting against powerful forces...The book is about knowing the past and knowing your power."Literary Hub

-

"[A] groundbreaking new work of recovered history... Devlin, a Rutgers University historian, spent ten years tracking down and interviewing dozens of women who endured harassment and abuse to desegregate schools, whether or not their lawsuits prevailed...Devlin's chronicle...promises to reignite public conversation and debate about racial disparities in public education."Smithsonian

-

"The decade of work Devlin put into recovering this underappreciated aspect of civil-rights history is fully on display."Booklist

-

"In this accomplished history of the school desegregation fight from the late 1940s through the mid-1960s, Devlin...offers a cogent overview of the legal strategies employed and delves into the stories of the African-American girls (and their families) who defied the ignominious public school systems of the Jim Crow South....Devlin's use of diverse secondary and primary sources, including her own interviews with some of the surviving women, bring fresh perspectives. This informative account of change-making is well worth reading."Publishers Weekly

-

"A thoroughly researched, well-written work about civil rights, American history, and the momentum of political change that young people, particularly women, initiate."Library Journal

-

"Before reading A Girl Stands at the Door I would have imagined that nothing new could be said about the struggle to desegregate schools--and I would have been wrong. Rachel Devlin has uncovered a neglected history of how parents and, importantly, children braved rejection, hostility, even assault to insist on their right to a decent education. Possibly most surprising, these courageous students were mostly girls, a finding that challenges some assumptions about risk-taking behavior. Not least, the book is a great read."Linda Gordon, author of The Second Coming of the KKK

-

"Bold and unforgettable, the girls whose vivid portraits Devlin brings to life through priceless interviews should be household names for their moral courage and stalwart persistence in challenging segregated schools despite the personal costs. This book brings underrecognized female leadership in the black freedom struggle dramatically to the forefront, redrawing the known landmarks in that history."Nancy F. Cott, Jonathan Trumbull Professor of American History, Harvard University

-

"A Girl Stands at the Door reveals black girls' under-appreciated role in the Civil Rights Movement. Devlin relates the stories of well-known child activists such as Ruby Bridges, as well as the stories of numerous other brave black girls whose names have been forgotten by many. The book follows black girls down the halls of schools from Missouri, Oklahoma, Kansas, Louisiana, Texas, and Virginia. The stories unveil much about the struggles of black girls' daily lives and their steadfast determination to find a way in an often hostile world."LaKisha Michelle Simmons, author of Crescent City Girls

-

"A Girl Stands at the Door forces us to view a central strand of civil rights history in an entirely new way. Rachel Devlin has discovered something that should have been in plain view but nonetheless has remained invisible - that girls and young women stood at the center of the massive effort to desegregate American schools. In this compelling, lucid, and deeply researched book, Devlin makes them into flesh-and-blood actors, whose words, initiative, and subtle everyday negotiations helped shape an important strand of American history."Kenneth Mack, professor, Harvard Law School and author of Representing the Race

- On Sale

- May 15, 2018

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541697331

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use