By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

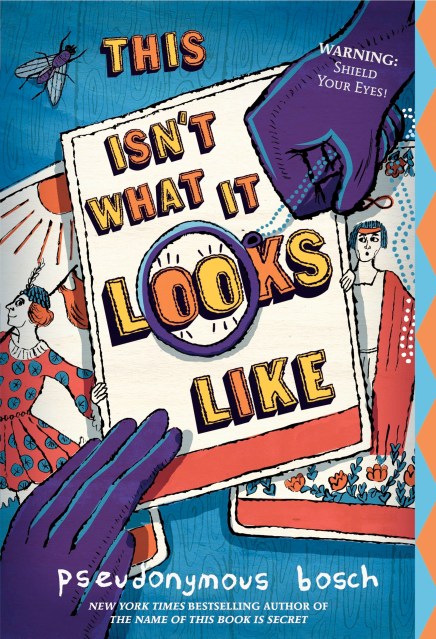

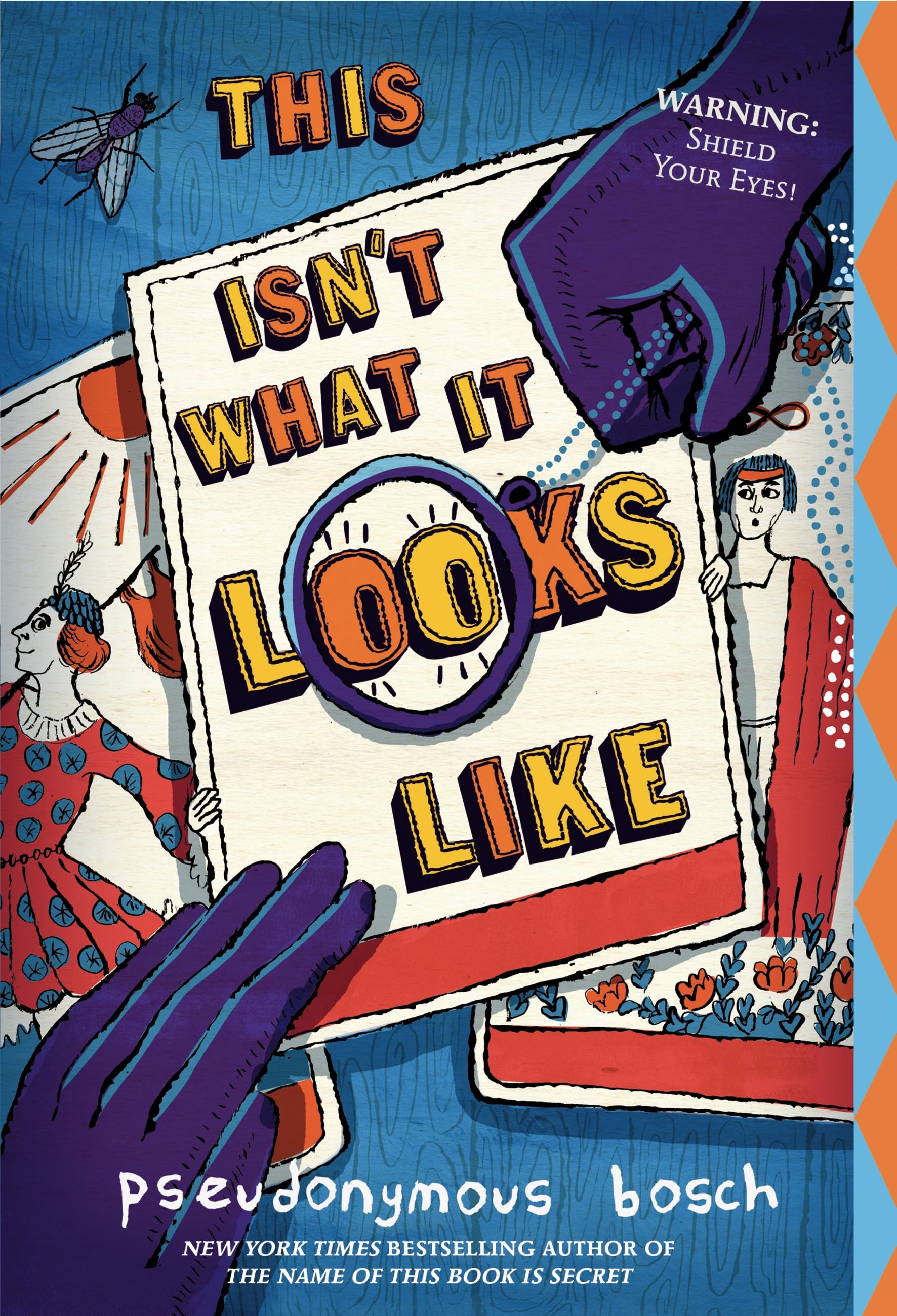

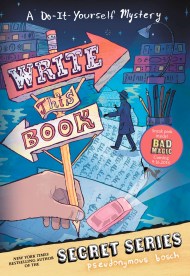

This Isn't What It Looks Like

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- ebook $7.99 $9.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 5, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

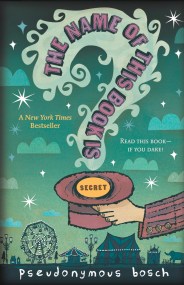

Cass finds herself alone and disoriented, a stranger in a dream-like, medieval world. Where is she? Who is she? With the help of a long-lost relative, she begins to uncover clues and secrets–piecing together her family’s history as she fights her way back to the present world.

Meanwhile, back home, Cass is at the hospital in a deep coma. Max-Ernest knows she ate Time Travel Chocolate–and he’s determined to find a cure. Can our expert hypochondriac diagnose Cass’s condition before it’s too late? And will he have what it takes to save the survivalist?

Series:

- On Sale

- Sep 5, 2011

- Page Count

- 448 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9780316076241

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use