Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

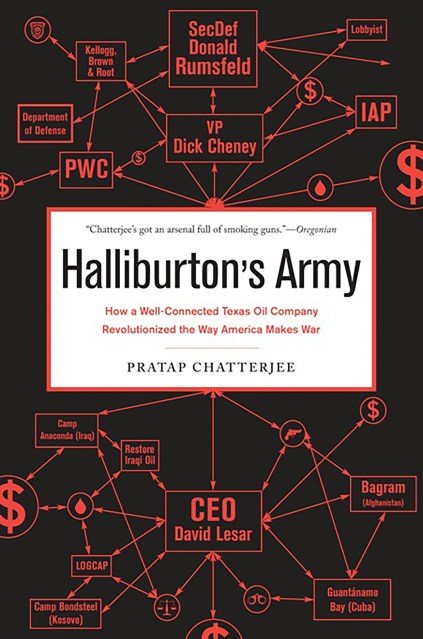

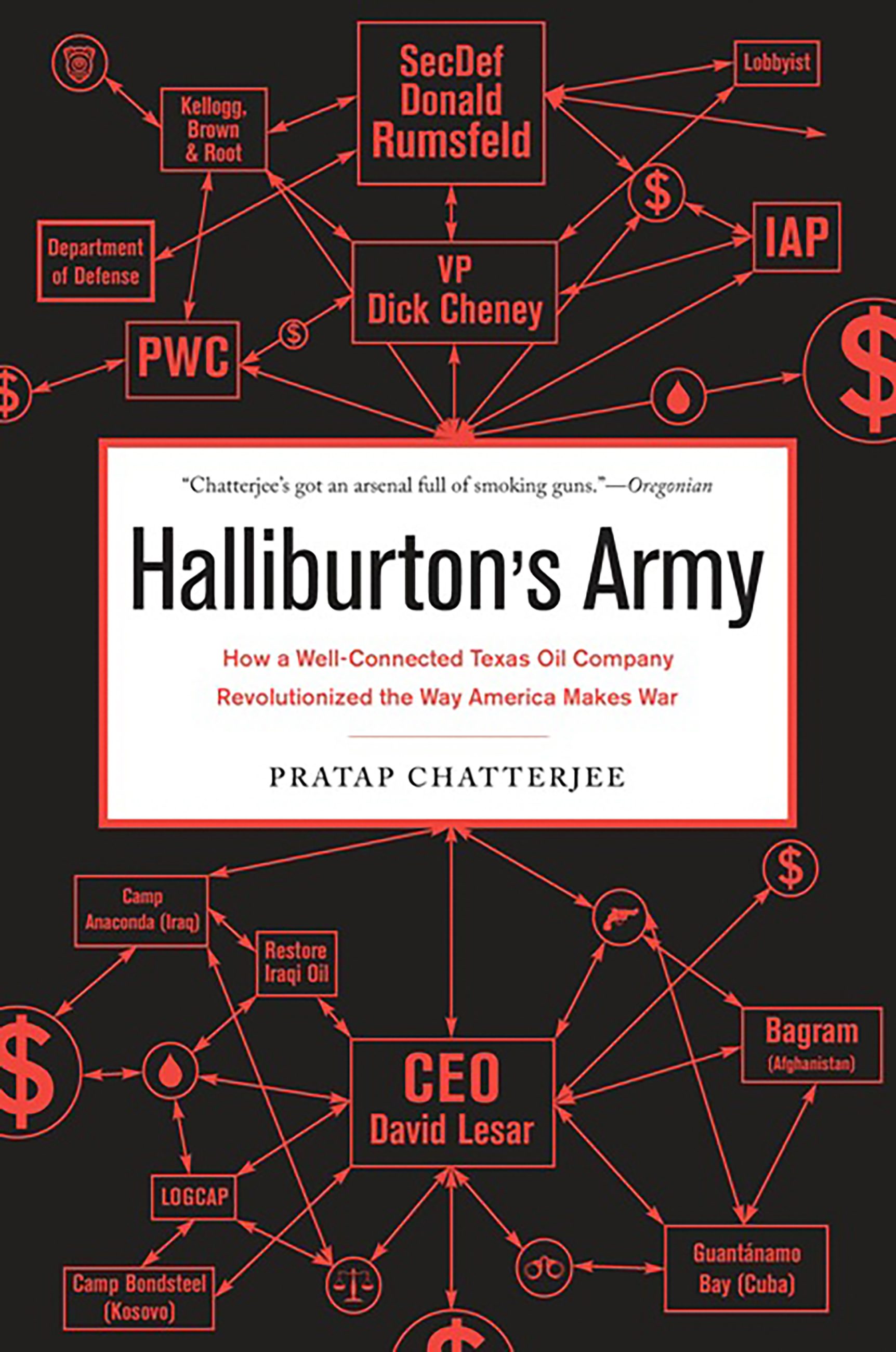

Halliburton's Army

How a Well-Connected Texas Oil Company Revolutionized the Way America Makes War

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $11.99 $15.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 23, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Pratap Chatterjee — one of the world’s leading authorities on corporate crime, fraud, and corruption — shows how Halliburton won and then lost its contracts in Iraq, what Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld did for it, and who the company paid off in the U.S. Congress. He brings us inside the Pentagon meetings, where Cheney and Rumsfeld made the decision to send Halliburton to Iraq — as well as many other hot-spots, including Somalia, Yugoslavia, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Guantámo Bay, and, most recently, New Orleans. He travels to Dubai, where Halliburton has recently moved its headquarters, and exposes the company’s freewheeling ways: executives leading the high life, bribes, graft, skimming, offshore subsidiaries, and the whole arsenal of fraud. Finally, Chatterjee reveals the human costs of the privatization of American military affairs, which is sustained almost entirely by low-paid unskilled Third World workers who work in incredibly dangerous conditions without any labor protection.

Halliburton’sArmy is a hair-raising exposéf one of the world’s most lethal corporations, essential reading for anyone concerned about the nexus of private companies, government, and war.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 23, 2010

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780786743698

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use