Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

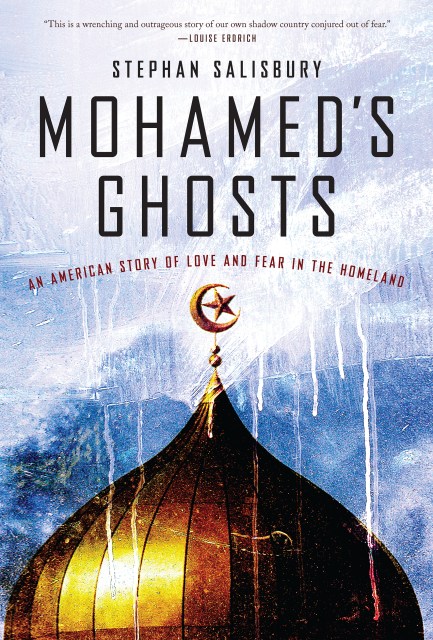

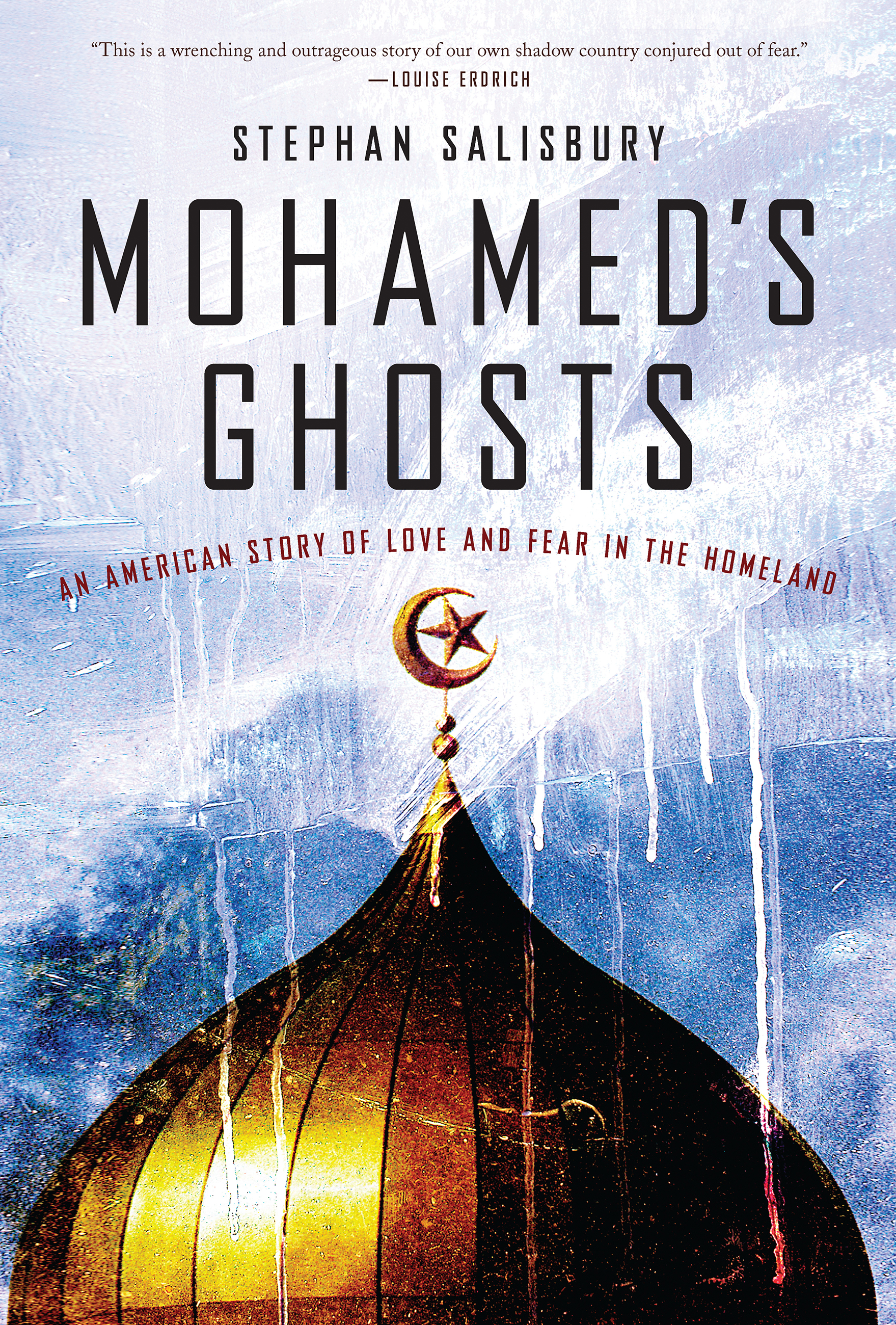

Mohamed's Ghosts

An American Story of Love and Fear in the Homeland

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $17.99 $22.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 27, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

This was a jumpy and fearful time in the life of America following 9/11, as prize-winning reporter Stephan Salisbury well knew. But he did not anticipate the extremity of fear that emerged as he explored the aftermath of that virtually forgotten raid. Over time, the members of the mosque and the imam’s family gradually opened up to him, giving Salisbury a unique opportunity to chronicle the demolition of lives and families, the spread of anti-immigrant hysteria, and its manipulation by the government. As he explores events centered on what he calls “the poor streets of Frankford Valley” in Philadelphia, or the empty streets of Brooklyn , or the fear-encrusted precincts of Lodi, California and beyond, Salisbury is constantly reminded of similar incidents in his own past–the paranoia and police activity that surrounded his political involvement in the 1960s, and the surveillance and informing that dogged his father, a well-known New York Times reporter and editor, for half a century. Salisbury weaves these strands together into a personal portrait of an America fracturing under the intense pressure of the war on terror — the Homeland in the time of Osama.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 27, 2010

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568586236

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use