Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

To Build a Better World

Choices to End the Cold War and Create a Global Commonwealth

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 10, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A deeply researched international history and “exemplary study” (New York Times Book Review) of how a divided world ended and our present world was fashioned, as the world drifts toward another great time of choosing.

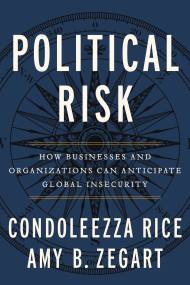

Two of America’s leading scholar-diplomats, Philip Zelikow and Condoleezza Rice, have combed sources in several languages, interviewed leading figures, and drawn on their own firsthand experience to bring to life the choices that molded the contemporary world. Zeroing in on the key moments of decision, the might-have-beens, and the human beings working through them, they explore both what happened and what could have happened, to show how one world ended and another took form. Beginning in the late 1970s and carrying into the present, they focus on the momentous period between 1988 and 1992, when an entire world system changed, states broke apart, and societies were transformed. Such periods have always been accompanied by terrible wars — but not this time.

This is also a story of individuals coping with uncertainty. They voice their hopes and fears. They try out desperate improvisations and careful designs. These were leaders who grew up in a “postwar” world, who tried to fashion something better, more peaceful, more prosperous, than the damaged, divided world in which they had come of age. New problems are putting their choices, and the world they made, back on the operating table. It is time to recall not only why they made their choices, but also just how great nations can step up to great challenges.

Timed for the thirtieth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, To Build a Better World is an authoritative depiction of contemporary statecraft. It lets readers in on the strategies and negotiations, nerve-racking risks, last-minute decisions, and deep deliberations behind the dramas that changed the face of Europe — and the world — forever.

Two of America’s leading scholar-diplomats, Philip Zelikow and Condoleezza Rice, have combed sources in several languages, interviewed leading figures, and drawn on their own firsthand experience to bring to life the choices that molded the contemporary world. Zeroing in on the key moments of decision, the might-have-beens, and the human beings working through them, they explore both what happened and what could have happened, to show how one world ended and another took form. Beginning in the late 1970s and carrying into the present, they focus on the momentous period between 1988 and 1992, when an entire world system changed, states broke apart, and societies were transformed. Such periods have always been accompanied by terrible wars — but not this time.

This is also a story of individuals coping with uncertainty. They voice their hopes and fears. They try out desperate improvisations and careful designs. These were leaders who grew up in a “postwar” world, who tried to fashion something better, more peaceful, more prosperous, than the damaged, divided world in which they had come of age. New problems are putting their choices, and the world they made, back on the operating table. It is time to recall not only why they made their choices, but also just how great nations can step up to great challenges.

Timed for the thirtieth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, To Build a Better World is an authoritative depiction of contemporary statecraft. It lets readers in on the strategies and negotiations, nerve-racking risks, last-minute decisions, and deep deliberations behind the dramas that changed the face of Europe — and the world — forever.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 10, 2019

- Page Count

- 528 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781538764664

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use