Promotion

Use code FALL24 for 20% off sitewide!

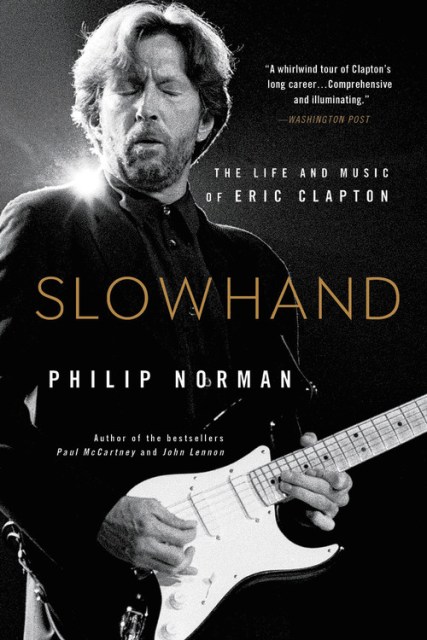

Slowhand

The Life and Music of Eric Clapton

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$19.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 19, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

From the bestselling author of Shout!, comes the definitive biography of Eric Clapton, a Rock legend whose life story is as remarkable as his music, which transformed the sound of a generation.

For half a century Eric Clapton has been acknowledged to be one of music’s greatest virtuosos, the unrivalled master of an indispensable tool, the solid-body electric guitar. His career has spanned the history of rock, and often shaped it via the seminal bands with whom he’s played: the Yardbirds, John Mavall’s Bluesbreakers, Cream, Blind Faith, Derek and the Dominoes. Winner of 17 Grammys, the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame’s only three-time inductee, he is an enduring influence on every other star soloist who ever wielded a pick.

Now, with Clapton’s consent and access to family members and close friends, rock music’s foremost biographer returns to the heroic age of British rock and follows Clapton through his distinctive and scandalous childhood, early life of reckless rock ‘n’ roll excess, and twisting & turning struggle with addiction in the 60s and 70s. Readers will learn about his relationship with Pattie Boyd — wife of Clapton’s own best friend George Harrison — the tragic death of his son, which inspired one of his most famous songs, “Tears in Heaven,” and even the backstories of his most famed, and named, guitars.

Packed with new information and critical insights, Slowhand finally reveals the complex character behind a living legend.

For half a century Eric Clapton has been acknowledged to be one of music’s greatest virtuosos, the unrivalled master of an indispensable tool, the solid-body electric guitar. His career has spanned the history of rock, and often shaped it via the seminal bands with whom he’s played: the Yardbirds, John Mavall’s Bluesbreakers, Cream, Blind Faith, Derek and the Dominoes. Winner of 17 Grammys, the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame’s only three-time inductee, he is an enduring influence on every other star soloist who ever wielded a pick.

Now, with Clapton’s consent and access to family members and close friends, rock music’s foremost biographer returns to the heroic age of British rock and follows Clapton through his distinctive and scandalous childhood, early life of reckless rock ‘n’ roll excess, and twisting & turning struggle with addiction in the 60s and 70s. Readers will learn about his relationship with Pattie Boyd — wife of Clapton’s own best friend George Harrison — the tragic death of his son, which inspired one of his most famous songs, “Tears in Heaven,” and even the backstories of his most famed, and named, guitars.

Packed with new information and critical insights, Slowhand finally reveals the complex character behind a living legend.

-

"Norman chronicles Clapton's life and music from the Yardbirds and Cream through his solo career."No Depression

-

"The renowned guitar superhero emerges as 'supersurvivor' in this authoritative biography...Extremely knowledgeable about the rock music scene, Norman tells Clapton's story with verve and insight."Kirkus

-

"Among music book scribes, Philip Norman stands near the top in terms of influence and skill. Now, he turns his attention to classic rock's most revered guitarist and often reluctant front man, Eric Clapton. Norman's stab... will likely go down as the definitive work of the man ... a comprehensive and deep dive into a singular pool of talent."Houston Press

-

"Comprehensive and illuminating."The Washington Post

-

"An intimate tour of his personal white room with black curtains."The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

- On Sale

- Nov 19, 2019

- Page Count

- 448 pages

- Publisher

- Back Bay Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316560467

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use