Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

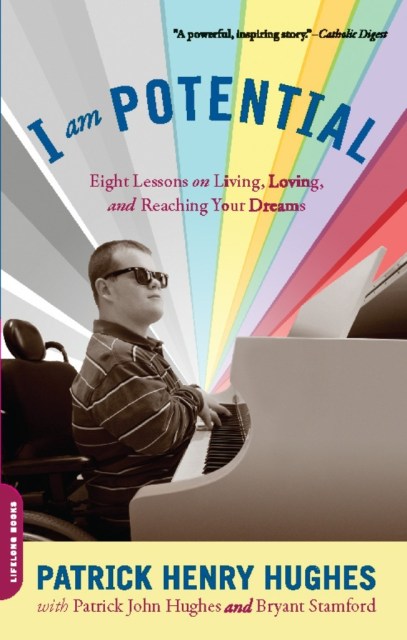

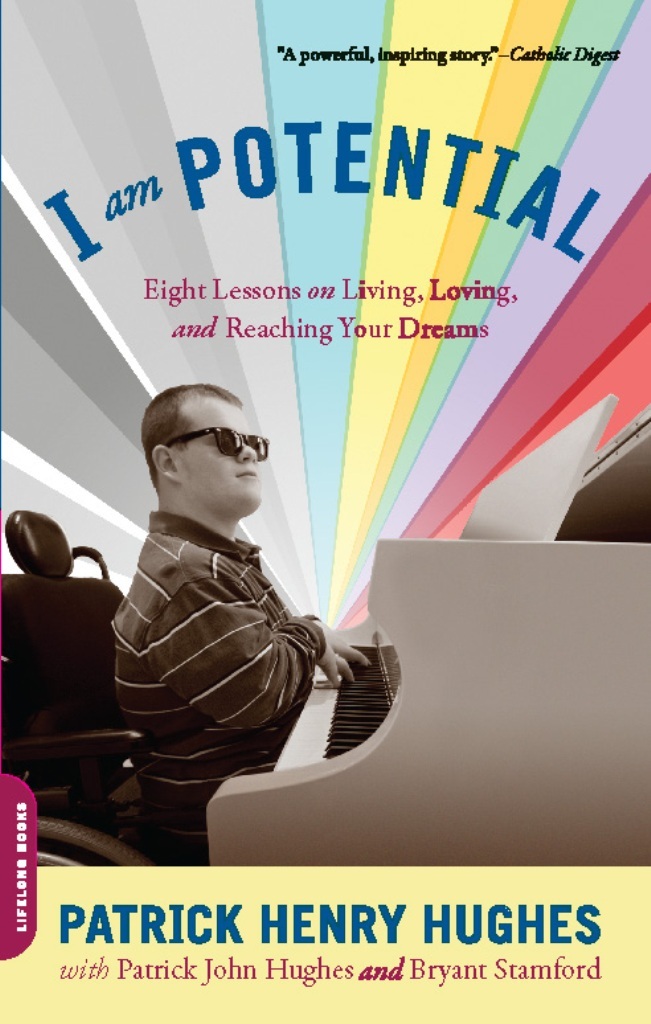

I Am Potential

Eight Lessons on Living, Loving, and Reaching Your Dreams

Contributors

With Bryant Stamford

Formats and Prices

Price

$1.99Price

$2.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $1.99 $2.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 25, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Now, for the first time, Hughes and his father share the full account of his extraordinary journey. In I Am Potential, Hughes recounts the eight critical lessons he has learned that are at the heart of his success, including “When Life Gives You Lemons, Accept Them and Be Grateful” and “Do All You Can to Change What You Can.” Uplifting and revealing, I Am Potential is remarkably inspirational for anyone facing challenges in their own life.

Genre:

-

Blogcritics.org, 8/27/09

“[A] heroic story.”

Blogcritics.org, 8/17/09

“This book is a must read for people with handicapping conditions from birth or from fate. Patrick’s courage and the support given by mother, father, and brothers as he grew older, cannot help but inspire even the most depressed individual to accept a disabling condition and move forward. I Am Potential is fascinating to read…I cannot recommend this book highly enough to the general public who often see people with a handicap as a handicapped person. Patrick has proven the two terms are not equal or even logical.”

Acadiana LifeStyle LA, October 2009

“This story of parental love and a persevering child should lift your spirits and encourage you to discover and pursue your own potential.”

Midwest Book Review, December 2009

“Both a memoir of achievement and an inspirational account perfect for any general library strong in positive 'can-do' guides.”

Alaska Journal of Commerce, 12/13/09

“Any businessperson who needs motivation needs I Am Potential…Not only is this a book that puts things into perspective, but it’s also a darn good story.”

- On Sale

- Aug 25, 2009

- Page Count

- 264 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Lifelong Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780786726684

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use