By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

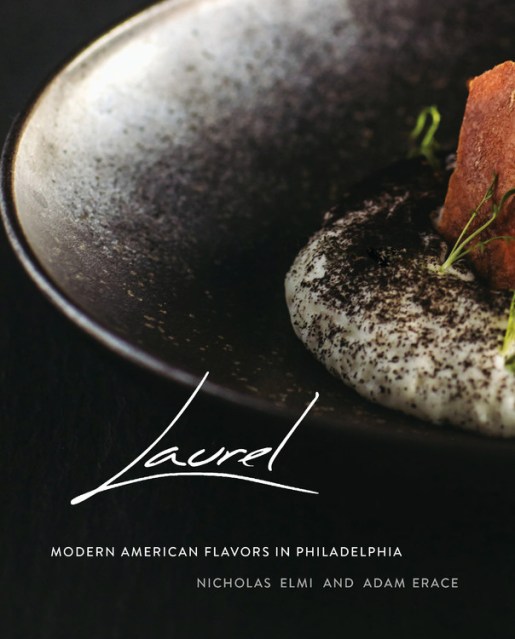

Laurel

Modern American Flavors in Philadelphia

Contributors

By Adam Erace

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 17, 2019

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762491735

Price

$35.00Price

$45.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $35.00 $45.50 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 17, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

An Exquisite Seasonal Tasting Menu from the Heart of South Philly

Laurel, the first book from restaurateur and Top Chef winner Nicholas Elmi, promises to be as engrossing and delicious as its restaurant namesake, a culinary stronghold in South Philly.

Elmi’s French background and training informed Laurel from the start, but Laurel is a true American restaurant with a modern feel. The acclaimed nine-course tasting menu is unmatched in Philadelphia. Elmi does seasonality just right.

The book is also a letter of gratitude to the restaurant’s suppliers, whose work colors every dish they serve. Each chapter is a full nine-course tasting menu with accompanying cocktail, and almost as delicious on the page as the meal itself.

Laurel, the first book from restaurateur and Top Chef winner Nicholas Elmi, promises to be as engrossing and delicious as its restaurant namesake, a culinary stronghold in South Philly.

Elmi’s French background and training informed Laurel from the start, but Laurel is a true American restaurant with a modern feel. The acclaimed nine-course tasting menu is unmatched in Philadelphia. Elmi does seasonality just right.

- Fall brings Apple-Yuzu Consommé, Marinated Trout Roe, and Bitter Greens.

- Winter serves up Bourbon-Glazed Grilled Lobster, Crunchy Grains, and Apple Blossom,

- Spring is evidenced by Black Sea Bass, Peas, and Rhubarb

- Summer is distilled in Marigold-Compressed Kohlrabi, Buckwheat, and Cured Egg.

The book is also a letter of gratitude to the restaurant’s suppliers, whose work colors every dish they serve. Each chapter is a full nine-course tasting menu with accompanying cocktail, and almost as delicious on the page as the meal itself.

-

"This gloriously photographed book does belong on a coffee table, or at least a bar, so that even if you're not cooking the recipes you can at least imagine them in an aspirational way."-Forbes

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use