Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

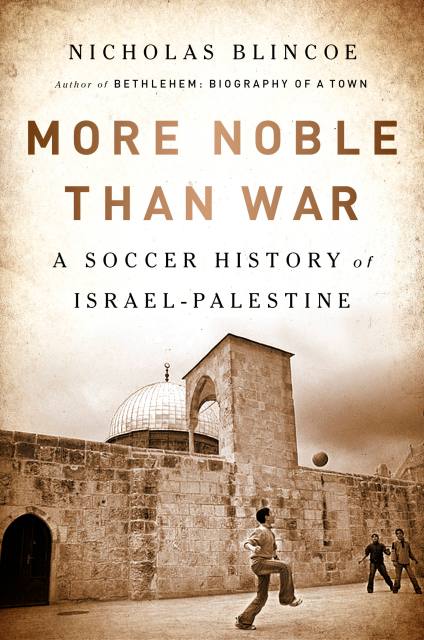

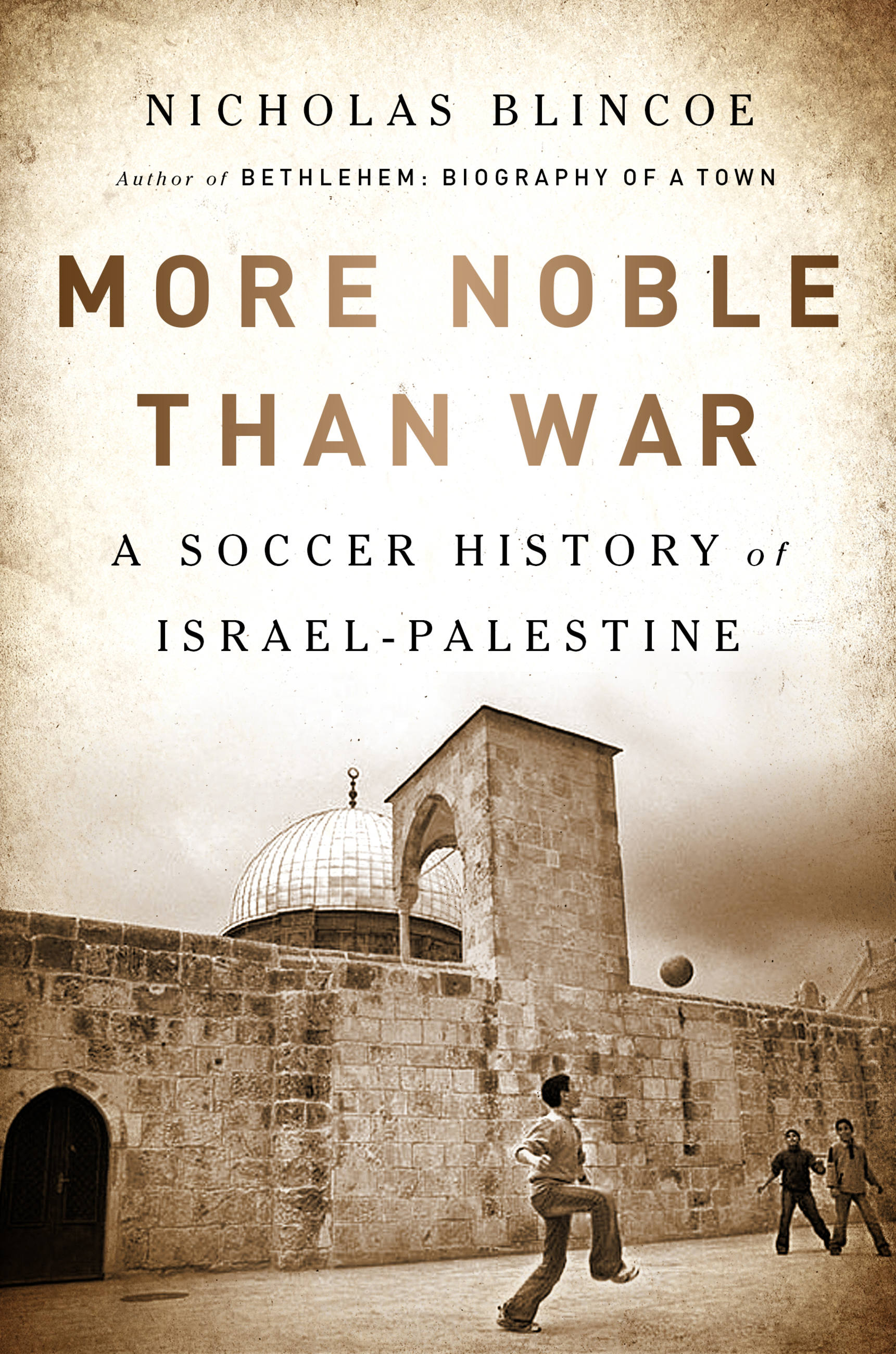

More Noble Than War

A Soccer History of Israel-Palestine

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 29, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

By turns tragic and hopeful, the history of Israel and Palestine through the lens of the world’s most popular sport

In More Noble Than War, Nicholas Blincoe weaves a dramatic narrative filled with driven players and coaches who are inspired as much by nationalism as a love of the game. Blincoe traces the history from the sport’s introduction through church leagues, he rising tensions after the creation of Israel, and the decades of violence, war, and hunger strikes that have decimated teams.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 29, 2019

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568588872

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use