Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

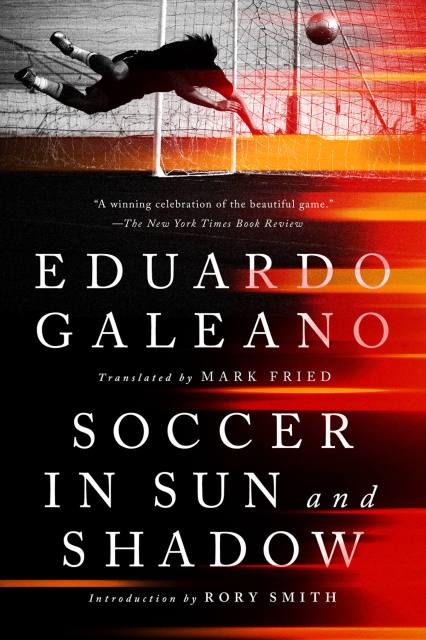

Soccer in Sun and Shadow

Contributors

Introduction by Rory Smith

Formats and Prices

Price

$18.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 18, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In this witty and rebellious history of world soccer, award-winning writer Eduardo Galeano searches for the styles of play, players, and goals that express the unique personality of certain times and places. In Soccer in Sun and Shadow, Galeano takes us to ancient China, where engravings from the Ming period show a ball that could have been designed by Adidas to Victorian England, where gentlemen codified the rules that we still play by today and to Latin America, where the “crazy English” spread the game only to find it creolized by the locals.

All the greats—Pelé, Di Stéfano, Cruyff, Eusébio, Puskás, Gullit, Baggio, Beckenbauer— have joyous cameos in this book. yet soccer, Galeano cautions, “is a pleasure that hurts.” Thus there is also heartbreak and madness. Galeano tells of the suicide of Uruguayan player Abdón Porte, who shot himself in the center circle of the Nacional's stadium; of the Argentine manager who wouldn't let his team eat chicken because it would bring bad luck; and of scandal-riven Diego Maradona whose real crime, Galeano suggests, was always “the sin of being the best.”

Soccer is a game that bureaucrats try to dull and the powerful try to manipulate, but it retains its magic because it remains a bewitching game—“a feast for the eyes … and a joy for the body that plays it”—exquisitely rendered in the magical stories of Soccer in Sun and Shadow.

Genre:

-

Named one of the 'Top 100 Sports Books of All Time' by Sports Illustrated

-

"Soccer in Sun and Shadow is the most lyrical sports book ever written... In soccer, Galeano finds both a reflection and extension of everything he loves and finds maddening about the part of the world that has been the central focus of his writing for decades"Dave Zirin

-

"Between poetic descriptions of scores by famous players, Galeano provides political context and commentary... over all, the book is a winning celebration of the beautiful game."New York Times Book Review

-

"A poetic history [of soccer] that sets the book apart from others. Galeano's Catholic upbringing, socialist politics, and the injustice he's seen as a journalist seeps into his commentary, and gives his narrative a refreshing perspective that captures soccer's spiritual roots, corruption by greed, and role as a global equalizer that puts royals and dictators at the mercy of minorities and slum kids."Publishers Weekly

-

"This updated edition serves as a reminder that this is not just a classic sports book. On virtually every page, Galeano uses a phrase or sentence that will leave readers in awe of his gifts. A welcome update of a classic. Galeano's gift to the game he loves."Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

-

"Since its first publication in 1995 (as Football in Sun and Shadow), this book has been relentlessly quoted, and for good reason. The author who pleads, 'A pretty move, for the love of God' has an eye for beauty, a feel for the game, a sense of proportion-and a gift for putting it all into words. Those seeking a history of soccer or a fan's memoir won't find it here... Above all, he reminds us of 'a simple truth that tends to escape the scientists of the ball: soccer is a game, and those who really play it feel happy and make us happy too.' An indispensible addition to soccer collections"Booklist, (starred review)

-

"It's all here. Everything you should know about soccer, the world's game"Los Angeles Times

-

"Stands out like Pele; on a field of second-stringers."New Yorker

-

"[A] beautiful ode to the beautiful game."Grant Wahl, Sports Illustrated

-

"The Pele of [soccer] writing....a marvelous book."Richard Williams, The Guardian

- On Sale

- Oct 18, 2022

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781645030379

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use